I made an unexpected appearance in the Times Literary Supplement this week. The poet Craig Raine, reminiscing about some of his favourite similes, suddenly remembered something he didn’t like:

Ten years ago, the critic Jeremy Noel-Tod was convicting Ted Hughes of “descriptive decadence”, comparing him to R.F. Langley, a poet of modest, even meagre, descriptive gifts.

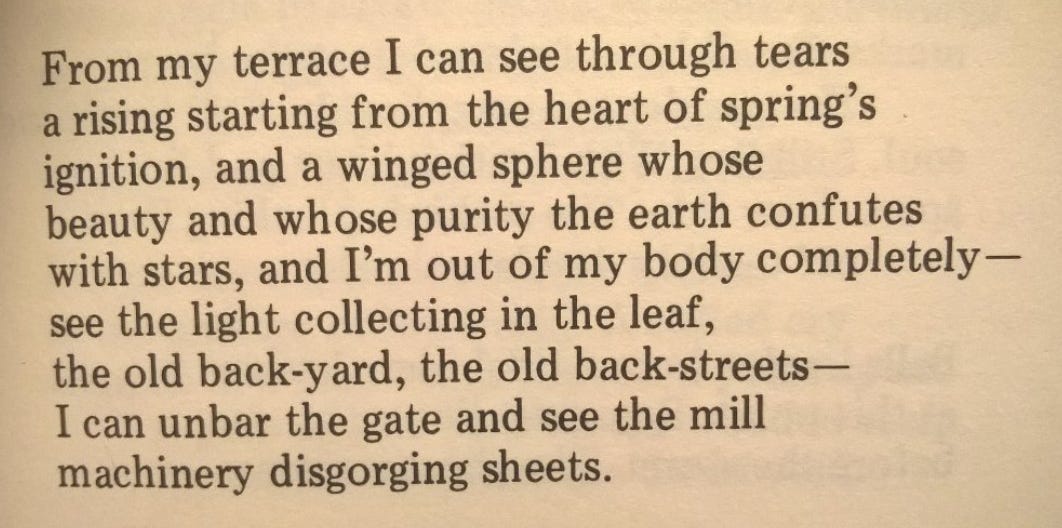

It’s true I said this: but it was fourteen years ago, and in a TLS review of Michael Haslam’s Mid Life: Poetry 1980-2000 (Shearsman). It’s very much the work of a critic who was also handing in his PhD thesis that month. Nevertheless, it reminded me how much I like Haslam’s humorous, musical, unHughesian mysticism. Here’s an edited version:

In his 1973 study, Thomas Hardy and British Poetry, Donald Davie argued that industrialisation had diminished poetry’s “traditional images of celebration”. Two centuries after Wordsworth, the British landscape had been so thoroughly urbanised that no one could write of oaks or roses or nightingales with a “natural piety” that was not compromised by everyday reality. How, Davie wondered, “can we trust any longer the celebratory, hallowing potency which these images... have manifested in poetry of the past?”

The question contains the seed of its own answer. In the poetry of the past, these images were potent precisely because they were not real. Keats’s nightingale is not famous for its plumage; Yeats’s “far-off, most secret, and inviolate Rose” was not at the bottom of his garden. It was, in fact, Wordsworth who naturalised poetic piety, and initiated a tradition that brought us to the descriptive decadence of Hughes, where every thought fox has its own sharp hot stink.

But Wordsworth, as J.K. Stephen’s famous parody puts it, had two voices: one to observe that “grass is green, lakes damp, and mountains steep”; and one with “the form and pressure of high thoughts”. Observers of other orders of being are still at work in British poetry. One is Michael Haslam, whose reflexive poetics is declared in a couplet from Continual Song (1986), his early, magnificent long poem: “A falcon falling out upon the wind — / the vocal remnant of illumination so sustained”.

In finding a style with Continual Song, Haslam also settled into a subject: his own spiritual autobiography in the Upper Calder Valley of Yorkshire. It is a territory that he shares with Ted Hughes, who culled it of all but a few ur-Yorkshiremen in Remains of Elmet (1979). For Haslam, however, it is the modern community where he works as a casual labourer, “a spectre / of the black economy, filling my bucket / at the garden tap”.

In doing so, this exquisitely acoustic poet finds a symbol for the impurities of his own lyricism: “The gush jangles its drum — / cement has maimed its tone”. His natural descriptions exhibit an Elizabethan feel for aureate hazard: watching the wind on running water, he writes of how “its shining shakes the trickle shallows / over pillicules of quartzy grit”.

Concrete reality is important in underwriting such light-fancied exuberance. In the middle of Continual Song is a lyric that opens in “the slightest vacuum when the concrete mixer stops”. Mid Life’s pastoral is also Davie’s post-industrial landscape, where the wind “sounds through broken flats”, and Haslam’s recurrent theme is the maiming of himself as a gushing poet of pure tone.

The pathos of this is handled throughout with quick wit. In a new introduction, Haslam writes that “I attribute to my Lancashire background the ambition for the Poet to be, above all, a Comedian”. Continual Song succeeds best at keeping the joke fresh by its division into anecdotal sections, often taking off from the bodging of building odd-jobs (“I learned to fake... to make a show of coping like a proper man”).

What makes every page here worth reading, however, is the musical force with and by which the poetry is drawn: “the line entendrilled / locking to the key” as “Sothfastness” has it. Haslam’s springy free verse often lets slip perfect iambic pentameters with a flourish. “The cow’s mouth crops the thistle flower down”, for example, is patterned and balanced by a repeated vowel-pair (–ow –ow) which finishes on a word (“down”) that folds noun into preposition, detail into action.

The grammatical double-take is Haslam’s hallmark, and the life that ambiguous parts of speech lend his lines is the stylistic expression of his vision. Whether hiding a bawdy pun in the undergrowth (“The plum in heather blooms”) or hearing the anima of a waterfall — “The bell of animation babbles / beautifully golden well” — these poems put the Pan and the Psyche into panpsychism.

Haslam treats modern Britain as a spiritual landscape, but he is no pagan naïf. As he writes in the notes to Continual Song on his website: “there is a God, and His name is Richard Dawkins, Inventor of Memes, that take life as the Supernatural Fairies”. This is poetic contrarianism of the kind that has embarrassed the decorum of its times ever since Blake, but has delighted the history of English literature.

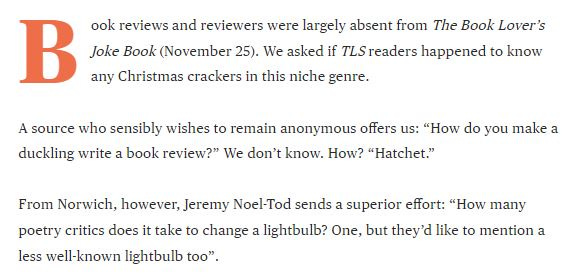

Oddly, Craig Raine’s potshot wasn’t my only TLS cameo this week — I also got a joke about poetry critics into the ‘N.B.’ column, as run by the discerning ‘M.C.’

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: