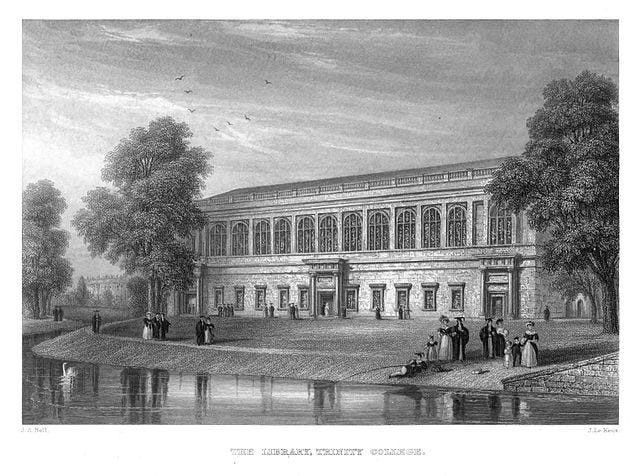

I’ve always had some sympathy with Charles Lamb’s melodramatic account of being shown the messy manuscript draft of John Milton’s “Lycidas” in the library of Trinity College, Cambridge:

I had thought of the “Lycidas” as of a full-grown beauty — as springing up with all its parts absolute — till, in evil hour, I was shown the original written copy of it […] I wish they had thrown them in the [River] Cam […] How it staggered me to see the fine things in their ore! interlined, corrected! as if their words were mortal, alterable, displaceable at pleasure! as if they might have been otherwise, and just as good! as if inspirations were made up of parts, and those fluctuating, successive, indifferent! I will never go into the work shop of any great artist again, nor desire a sight of his picture, till it is fairly off the easel.

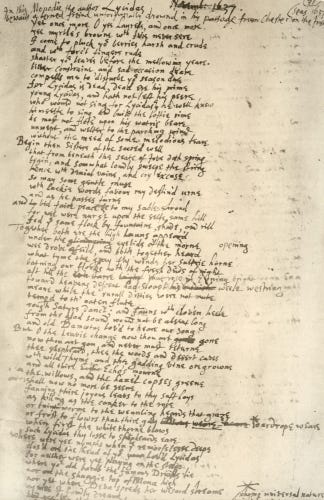

Here is the scribbly page, dated November 1637, that Lamb is describing:

If you look closely you can see, for example, that Milton has revised the phrase “glimmering eyelids of the morn” to “opening eyelids”. This is arguably not an improvement: the less conventional “glimmering” is good, I think, because it transfers the flickering of first light onto the flickering of eyes opening to see it.

But it’s too late to edit the classics of English poetry (“Hear me out: Lost Paradise”), and that is Lamb’s point: “opening eyelids” was what he knew — probably by heart — so “glimmering” could be thrown into the nearest river.

One of the pleasures of reading or reciting a favourite poem is the feeling that every word is right as it falls into place. But Lamb’s declaration that

I will never go into the work shop of any great artist again, nor desire a sight of his picture, till it is fairly off the easel

is going too far — because there is much memorable poetry that would have been lost altogether if somebody (a friend, an executor, a scholar) had not done exactly that.

The following, for example, is one of my favourite short poems by Lamb’s close friend, Wordsworth. But it was unknown to readers until published by Ernest de Selincourt in 1947, which means it has fallen outside the canon of famous Wordsworth poems:

Pressed with conflicting thoughts of love and fear

I parted from thee, Friend! and took my way

Through the great City, pacing with an eye

Downcast, ear sleeping, and feet masterless

That were sufficient guide unto themselves,

And step by step went pensively. Now, mark!

Not how my trouble was entirely hushed,

(That might not be) but how, by sudden gift,

Gift of Imagination’s holy power,

My Soul in her uneasiness received

An anchor of stability. It chanced

That while I thus was pacing, I raised up

My heavy eyes and instantly beheld,

Saw at a glance in that familiar spot

A visionary scene—a length of street

Laid open in its morning quietness,

Deep, hollow, unobstructed, vacant, smooth,

And white with winter’s purest white, as fair,

As fresh and spotless as he ever sheds

On field or mountain. Moving Form was none

Save here and there a shadowy Passenger

Slow, shadowy, silent, dusky, and beyond

And high above this winding length of street,

This moveless and unpeopled avenue,

Pure, silent, solemn, beautiful, was seen

The huge majestic Temple of St Paul

In awful sequestration, through a veil,

Through its own sacred veil of falling snow.

As Wordsworth’s biographer, Juliet Barker, remarks it is “a wonderful meditative poem”, but “despite its obvious quality, William deliberately suppressed it during his lifetime, for reasons that remain obscure”.

One reason may have been its association with unhappy experiences, as summarised in Barker’s Wordsworth: A Life (2000). The winter of 1807-08 had been long and severe, and it’s surprising to realise that the snowy scene the poem describes was early April.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.