Seasonal associations: the bright sun and cold wind this week — spring weather like iced water — reminded me of early April 2008, when I was heading home from a week in a caravan on a freezing clifftop in Wales.

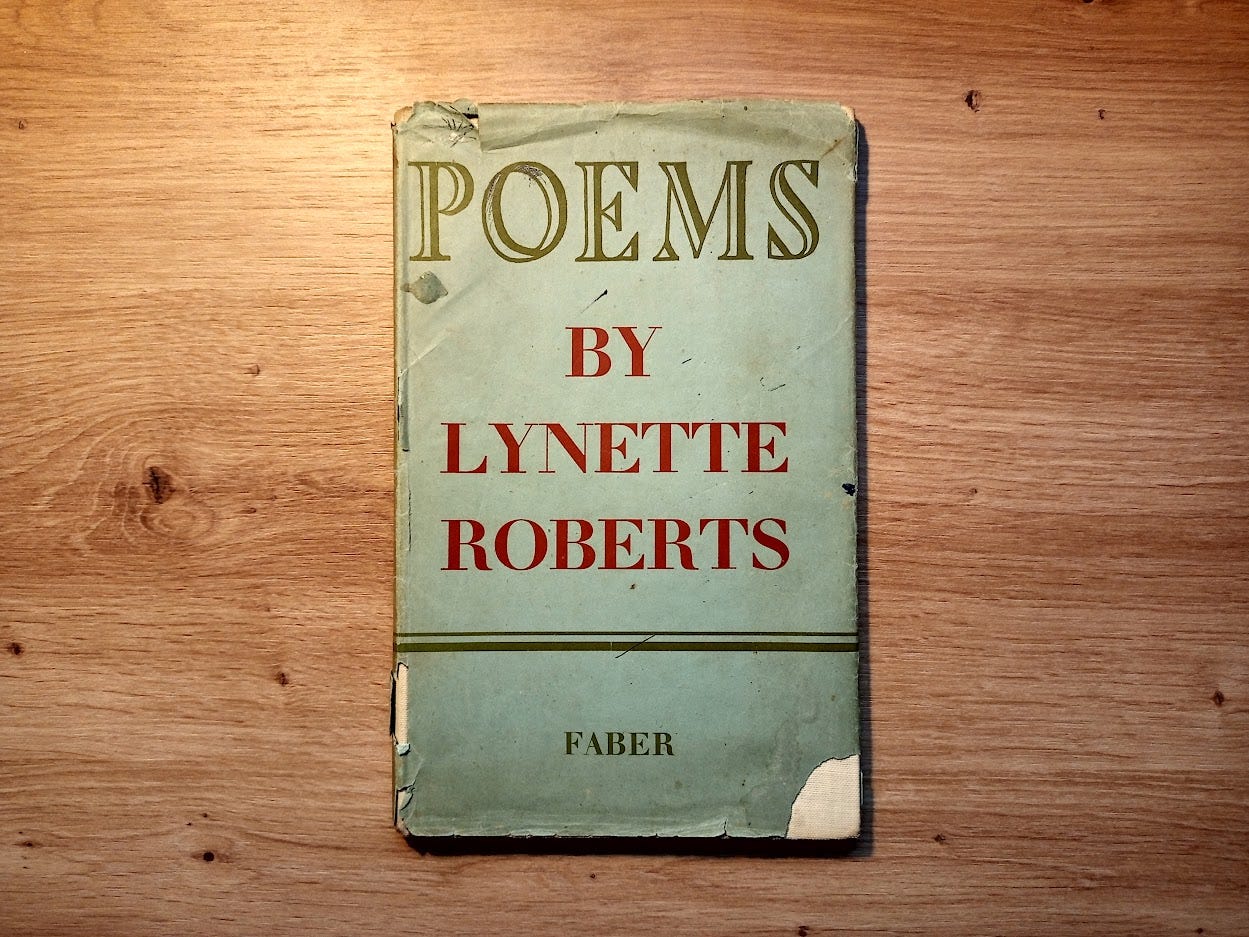

Driving through light snow, we stopped briefly in the village of Llanybri, where the poet Lynette Roberts once lived. Her unique poems from the 1940s had recently been restored to readers by Collected Poems (2005), edited by Patrick McGuinness. They evoke life in rural Wales with a wonderful cool vividness:

Of wood on which I washed, sat at peace:

Cooked duck, shot on an evening in peacock cold:

Studied awhile: wrote: baked bread for us both.(“The Shadow Remains”)

The din

Of children singing through the eyelet sheds

Ringing smith hoops, chasing the butt of hens;

Or I can offer you Cwmcelyn spreadWith quartz stones from the wild scratchings of men

(“Poem from Llanybri”)

The music of her syllables is finely modulated inside the rhythm of a speaking voice: notice how “din” rhymes distantly here with “hens”, having already echoed its way — like a runaway metal hoop — through “children singing… ringing… chasing”.

Just before leaving for Wales, I had written a review for the Guardian of a new volume of Roberts’ prose. For some reason, though, the piece never appeared — a pity, given its conclusion that she deserves new readers. So here it is now:

Lynette Roberts, Diaries, Letters and Recollections, ed. Patrick McGuinness (Carcanet, 2008)

Patrick McGuinness’ edition of Lynette Roberts’ Collected Poems (2005) restored a luminous voice to a posthumous readership. With this new collection of her prose, Roberts goes from being a lost poet to a lost person: a rare and unconventional mind left on the hard shoulder of the twentieth century.

The larger part of Diaries, Letters and Recollections is made up of “A Carmarthenshire Diary”, a previously unpublished account of Roberts’ life in the Welsh village of Llanybri in the 1940s. It was here that she wrote most of her poetry, but her independence from any precious notion of “being a poet” — rather than “a normal person who can take my full share of responsibility” — is declared on the first page: “I think good real living is more important than spreading yourself on paper”.

The statement is occasioned by a conversation with her new husband, Keidrych Rhys, the poet whose stewed apples she has just crossly prepared (“His ears are scarlet and I hate him”). Far from literary London, and with Rhys soon called away to the Army, Roberts turns from musing on “gutless poets” to her rural neighbours. The newcomer’s exploration of her environment is remarkable for its fingertip curiosity. After a hard frost, she reports that pieces of lime have broken from stone walls: “I am able to discover many of the previous colour washes of the village”. And when she sets herself to learning more about the local birdlife, she uses her oven as well as her eyes (the breast feathers of a pigeon exhibit “delicate gradings of grey, almost bronzed or tarnished on the uppermost layers” but “the dark and full breast of the Moorhen is even better to eat”).

Roberts studied Interior Decorating at art school in London, and her prose is that of a discerning colourist, whether describing wildflowers (“the clear shock pink of a Campion”) or her husband’s tie (a “mellow shade [...] which is to be found in old winebottles when the red of the wine still remains to the sides of the bottle”). But her fond investigations of the cottage culture of Llanybri are not rose-tinted. Digressions on the “dignity and pride” of craftsmen are quick to resist the back-to-the-land primitivism expounded by academics, “who seem to live backwards anyway”.

Instead, Roberts updates the Arts and Crafts argument for beauty and utility in a chemical world. “Coracles of the Towy”, an essay written for The Field magazine in 1945, presents a practical vision of a new life for the traditional fishing boat, “covered with synthetic textile made from the cellulose of reeds, and machine-sprayed with ICI plastics”.

The scientific precision here is continuous with the synthesising modernism of Roberts’ poetic imagination. The end of Gods with Stainless Ears (1951), her astonishing “heroic poem” about the Second World War, conjures a fourth dimension out of the “metallic convergences of words”, into which the poet escapes with her Singer sewing machine, “scrolled with gold, / Chromium wheel and black structure”.

In 1943, the younger writer reports her frustration at hearing Edith Sitwell declare grandly in favour of a return to poetic “simplicity”: “simplicity cannot be taken apart from its age, must be part of it [...] Pastoral ding dong is OUT”. As her diary attests, Lynette Roberts’ life in Wales was far from pastoral ding dong. The most lyrical pieces here are the “Seven Stories”, written to illustrate Roberts’ theory of the literary fitness of the “village dialect” she overheard. One symbol of these short, embroidered prose episodes is the pele fire, a mixture of coal dust, clay and water that keeps a hearth glowing steadily. At the end of the most intense story, “Swansea Raid”, the unnerving strangeness of seeing “cyanite blue” cows under bomber flares is relieved later by “a quiet clayfire with blue flames rising”.

The least polished – though nevertheless vivid – material is the concluding “Notes for an Autobiography”. This fills in fragments of Roberts’ Buenos Aires childhood and Soho salad days. But it also bears silent witness to her fate, having been written after she was sectioned under the Mental Health Act. Roberts’ descriptive memory remains keen as ever (her father’s Bentley had a “long strapped bonnet, cupped seats and wire wheels”). But it seems she wrote nothing so coherent again until her death in 1995.

Patrick McGuinness’ reconstruction of this and other pieces from typescript ranks him with T.S. Eliot — who first published her poems — as one of Roberts’ most determined supporters. Her 1948 account of going to meet Eliot at his London office, with her two small children running riot, is comic in outline (“They spat on the floor and tore up […] the pamphlets”). Through it, however, one can hear the strain of her struggle, after her marriage ended, to be both a responsible person and an experimental writer.

Yet Roberts resists pity, just as she avoids Eliot’s fatherly “falling cheek” at the end of their interview. What she deserves now is readers. Full of colour, fire and hope, Diaries, Letters and Recollections is the valuable testimony of an original thinker about literature and “good real living”.

NOTES

There’s a nice explanation of exactly what Roberts means by a “smith hoop” in “Poem from Llanybri” here: https://museum.wales/traditional_toys/hoop_and_hook/

You can read three late, uncollected poems by Lynette Roberts — including one evoking her Llanybri cottage, “Tygwyn” — here:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/browse?volume=82&issue=6&page=11

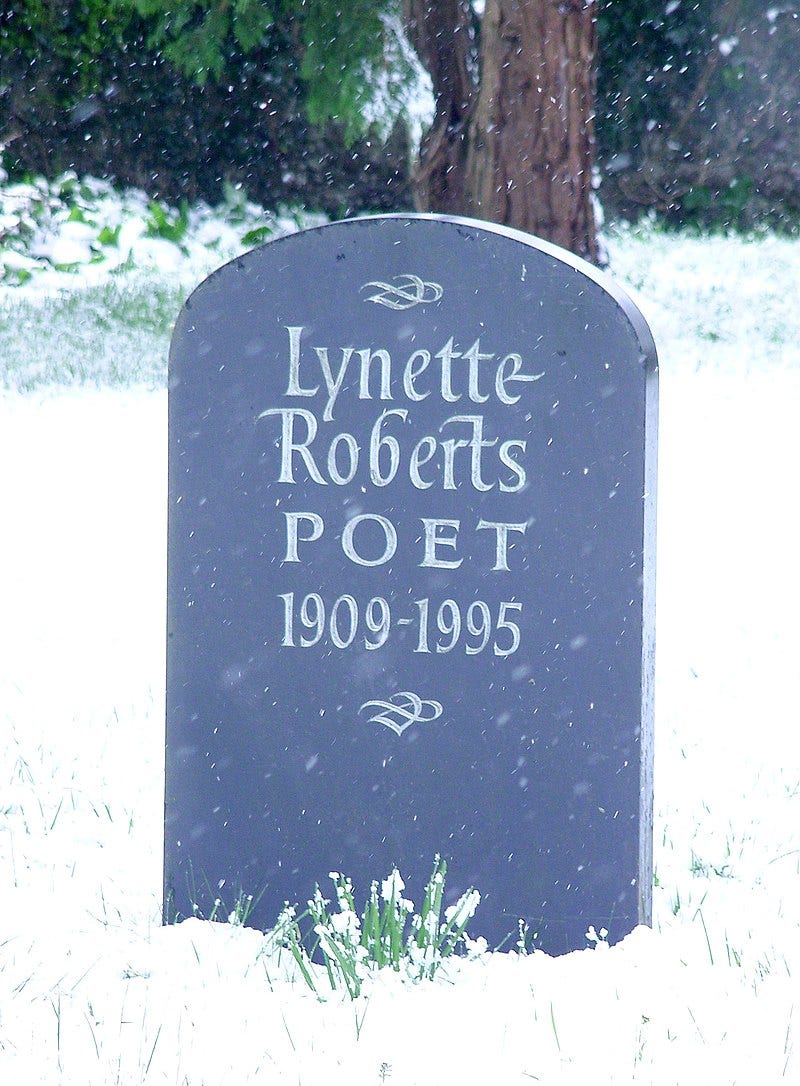

Lynette Roberts lived a long time after she stopped writing: her bold, beautifully lettered headstone was easy to find in Llanybri churchyard that snowy Sunday morning in April 2008 — and villagers leaving the church still remembered her.