How to Sell 10,000 Poetry Pamphlets

The extraordinary success of the Critical Quarterly supplements

It’s an unhappy time to be working in UK higher education. By next academic year, three-quarters of universities are predicted to be in deficit, with 10,000 jobs lost. At the University of East Anglia, where I work, it has just been announced that more posts are to go — the second time we’ve been in this situation in two years. The first time, I reduced my hours, and wrote this:

This week, I don’t have much add, except that I’m not expecting to be directly affected. But such cuts mean the collective loss of institutional knowledge — academic, technical, cultural, personal — that can’t be bought back. And all this is happening rapidly right across the country, and has in many ways been engineered by long-term government policy. I’m reminded of Geoffrey Hill’s lines from Canaan (1996), written at the end of the last Conservative government, of a nation “voiding / substance like quicklime”: “privatize to the dead / her memory”.

Universities are, among other things, sites of memory. And memory can at such times be a source of hope — to remember that things can be otherwise. So this week I’m sharing a revised version of a short history I wrote a few years ago about the academic journal Critical Quarterly and its extraordinary success as a publisher of new poetry — something that happened when “the worst university in England” (in the opinion of one poet) gave people who knew and cared about their subject the time and space needed to imagine a new way of doing things. It can be done.

In the tenth anniversary issue of Critical Quarterly, published in 1968, the journal’s founding editors, C.B. Cox and A.E. Dyson, reflected on their critical mission to broaden the audience for contemporary writing:

It has been of particular importance to us that we publish poetry alongside criticism, and a matter of pride that we have first published, for example, Philip Larkin’s “Love Songs in Age”, Ted Hughes’ “Hawk Roosting”, R.S. Thomas’ “Here”, Sylvia Plath’s “A Birthday Present”, Theodore Roethke’s “The Long Waters” and Thom Gunn’s “Back to Life”.

Choosing new poems for publication, they argued, “is an essential critical activity just as important as literary analysis itself”, contrasting their hospitable approach with F.R. Leavis’s Scrutiny magazine and its famously “negative attitude”. As well as mingling poems with essays and reviews, Critical Quarterly also ran poetry competitions for new writers, and published “an annual one shilling poetry pamphlet” comprising

twenty or so of the best of recently published poems. These pamphlets sell between 10,000 and 12,000 copies, and are much read by students.

When the first of these pamphlets, or “supplements”, Poetry 1960: An Appetiser, was announced in the third issue of the magazine in 1959, the editors said that

special efforts will be made to sell this to hundreds of people who have not looked at a poem since their formal education ended […] we are hoping that local representatives will sell the supplement in universities and other places; if you wish to help please write to let us know.

Warming to their sales pitch, they asked:

Why not buy ten copies to give to your friends? Or to use in class, if you teach? Or simply to have to hand when someone asks: “But what poetry is there today?”’

The place of poems in the original editorial vision of Critical Quarterly was, in other words, far more than a decorative filler between the essays and the adverts; it was central to a mission to educate.

If a pair of academics launched a magazine in the UK now and managed to sell 10,000-plus pamphlets of new poetry off the back of it annually, we would say they had one hell of an Impact Case Study on their hands. Modern university managers — for whom “impact” means research income — might rub their eyes in wonder to realise that Cox and Dyson did it largely out of enthusiasm, plus, in Cox’s own words, “plenty of spare time”. Looking back in 2008 on the “safe job for life” that he started in 1954 at the English Department at Hull, Cox remembered how

my total teaching load was about seven hours a week. On a typical day I would take a tutorial at 9.30 am, adjourn for coffee and possibly talk to friends until lunch.

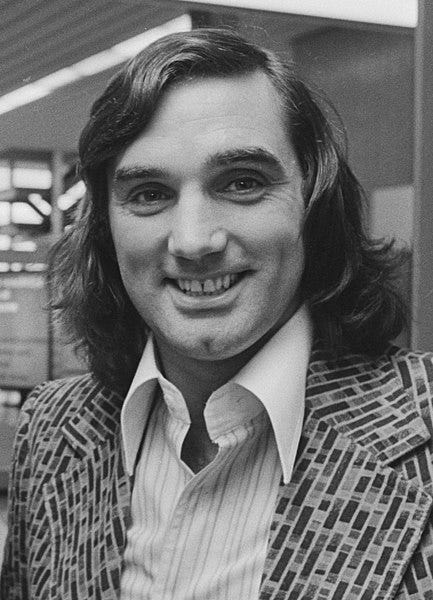

Enviously watching him across the Senior Common Room was Philip Larkin, who arrived as librarian in 1955, and liked to take a sceptical attitude towards the academic life (he teased Cox that he should try to get the notoriously hard-drinking footballer George Best a lectureship, after he was suspended by the Football Association). Larkin was nevertheless very supportive of the magazine, arranging for Oxford University Press to handle subscriptions, allocating Critical Quarterly its own office when a new library was built, and helping to judge the first poetry competition for poets who had not published a book — which resulted in the appearance in Poetry 1960 of a poem by Sylvia Plath, who went on to edit the second pamphlet, American Poetry Now (1961).

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.