It’s in the nature of the prose poem to feel second-hand: to resemble anecdote, essay, memory, or (often) dream diary. This is an observation on the nature of the form, rather than a criticism of its shortcomings. But it could of course be repurposed if you wanted to make the argument that ‘poetry = verse’. ‘Verse is a pedestrian taking you over the ground, prose—a train which delivers you at a destination’, said T.E. Hulme. Yet a train journey can be one of the wonders of modern life.

The echoing, self-distanced quality of much prose poetry is something that Luke Kennard’s Notes on the Sonnets (Penned in the Margins, 2021) — winner of this year’s Forward Prize — exploits in profound and moving ways, responding Shakespeare’s Sonnets with anecdotes, essays, memories and dreams about the nature of love, all told as attempts at conversation at a party. Kennard’s version of Sonnet 73 (‘That time of year thou may’st in me behold / When yellow leaves, or none, or few do hang’), for example, is a story about his child’s pure delight in the world of autumn, which concludes:

It causes me actual physical pain, how much I love him. As a child I liked to see otters in the zoo and I found them so endearing my reaction was to grind my teeth together so hard I’d chip them slightly and feel a film of fine grit in my mouth.

I could read Kennard’s prose poetry for a long time without tiring of the possibilities for poetic feeling it continues to discover around the corner of the next deft sentence. But when something is good and established, there are always imitations on the market, so it’s good to be reminded that there other ways into and out of the prose poem maze.

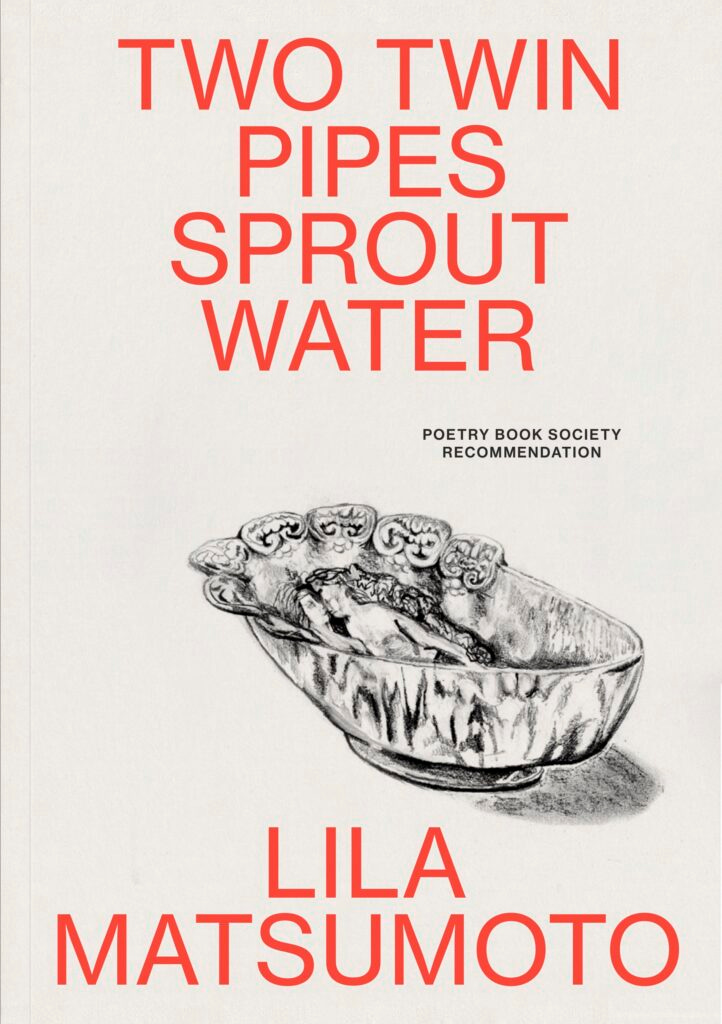

That was my thought reading a new book published by Prototype next week, which works the poetics of prose into structures and textures that become subtly less familiar. Lila Matsumoto’s Two Twin Pipes Sprouting Water (Prototype) is a book I’ve been looking forward to ever since her impressive debut, Urn & Drum (Shearsman, 2018), and it makes the most of the fact that her new publisher pays exquisite attention to detail in the making of books.

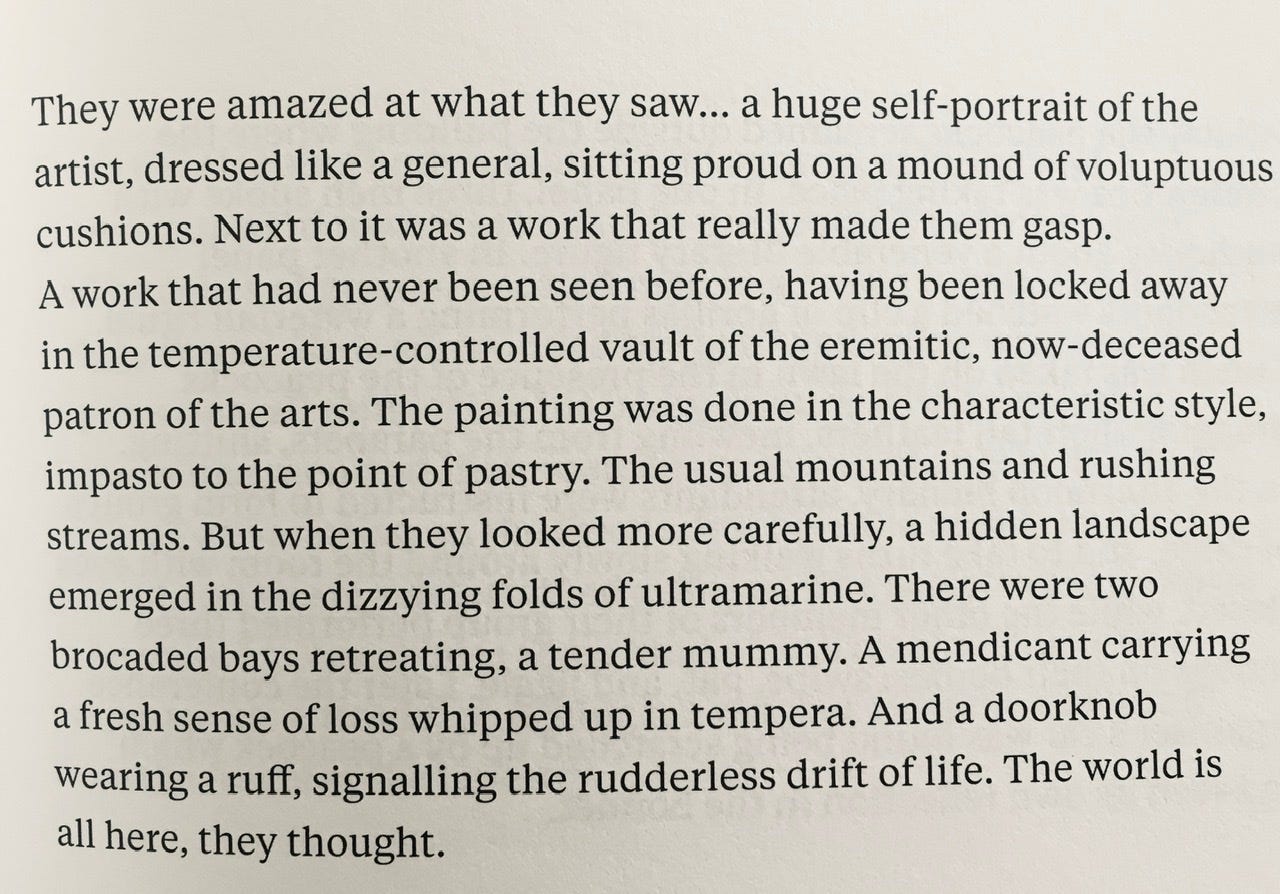

Cover to cover, Prototype poetry collections feel like complete works of art. And Matsumoto’s second book (which concludes on its title image) feels as though it has been organised as an inductive experience. The first section, ‘Pictorial programme’, draws the reader in through single-paragraph dream narratives that slowly turn up their solidly resistant strangeness. The increasing insistence on the singular experience of word choices as sound and picture can be traced in the following poem, ‘They were amazed at what they saw’:

This is a delicious exercise in one of the oldest traditions of the prose poem — which begins with the landscape ekphrasis of Aloysius Bertrand in Gaspard de la Nuit (1842) — renewed by Matsumoto’s rich and ironic play with English as a thickly three-dimensional medium (‘impasto to the point of pastry’). The ‘hidden landscape’ that emerges is the one that only words can create: second-hand description becomes physical immersion, like the moulded postcards you can buy in the Alps that allow your fingers to feel the contours of the mountains around you.

The latter sections of the book push this experience further, through typography (the pages of the second section employ a magnified font and storybook-style drop caps) and illustrations (the fourth part, ‘Eyebread’, pairs pencil drawings and short texts on facing pages). To experience it fully, you really have to have it in front of you — which is perhaps the best recommendation this second-hand prose can offer.