That huge dumb heap, that cannot tell us how,

Nor what, nor whence it is

Samuel Daniel, Musophilus (1599)

Today is the summer solstice — and the longest day — in the Northern Hemisphere. Last night, English Heritage offered overnight access to Stonehenge, allowing people to watch the sun rise in alignment with a boulder that stands directly beyond the stone circle. The schedule for this annual event is a drab little found poem of British life in itself:

I’ve never been to Stonehenge, or its car park. But its resonance in my imagination (and very possibly yours) seems to me an illustration of Wallace Stevens’ claim that the use of poetry is to imbue bare facts with emotional meaning. In his 1942 essay “The Noble Rider and the Sound of Words”, Stevens asks us to imagine a “collection of solid, static objects extended in space”:

and if we say that the space is blank space, nowhere, without colour, and that the objects, though solid, have no shadows and, though static, exert a mournful power, and without elaborating this complete poverty, if suddenly we hear a different and familiar description of the place:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres, and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

If we have this experience, we know how poets help people to live their lives.

The lines quoted are from Wordsworth’s sonnet “Composed upon Westminster Bridge, September 3, 1802”. I once taught Stevens’ essay to a class which included a student who had regularly commuted over Westminster Bridge while living in London — and who confirmed that she took pleasure in thinking of the poem every time.

Without imaginary associations — without memory — the world would be alien to us: “a collection of solid, static objects extended in space”. Which is also, of course, a description of Stonehenge if you didn’t have any memorable imaginary associations with the word “Stonehenge”.

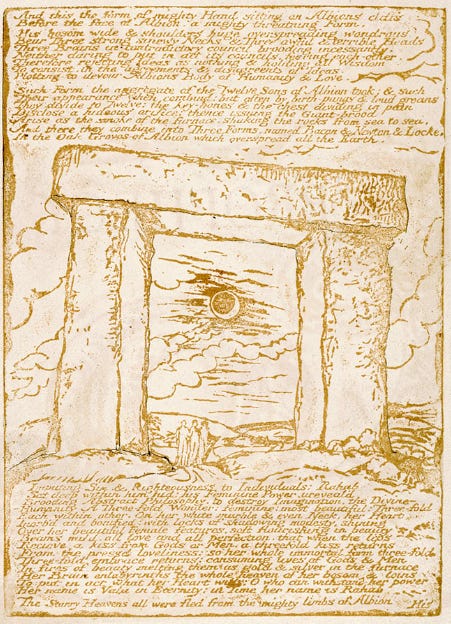

Standing stones have long inspired the instinct to myth. Early poetic references to Stonehenge allude to the legend that Merlin the wizard landed it there as a monument to Britons killed in battle, brought over from Ireland where giants had originally raised it on a mountain:

How Merlin by his skill, and magic’s wondrous might,

From Ireland hither brought the Stonehenge in a night.Michael Drayton, Poly-Olbion (1622)

But as Rosemary Hill observes in her excellent cultural history, Stonehenge (2008), it was “the balance of fact and imagination” in the mind of the antiquarian John Aubrey which first gave us our modern idea of Stonehenge as an ancient, ritual space. Aubrey’s observations in 1649 rejected the idea that it was the site of a battle, with the dead soldiers buried in “barrows” of piled earth:

Considering the barrows around Stonehenge and remembering the Civil Wars, he decided that they must mark ritual burials rather than the graves of the Britons […] After a battle, he noted, “soldiers have something els to do” than build elaborate tombs.

Nor, he reasoned, could stone circles — which are found across Britain and Ireland — be Roman, as others had speculated: “wherefore I conclude, that they were […] Temples of the Druids”.

It was that magical, mythical word “Druids” — dreaded by modern archaeologists — and the subsequent, fanciful association of their “temple” with human sacrifice that really fired up the later poets of Stonehenge. In 1773 a young Wordsworth found himself stranded on Salisbury Plain while travelling, and experienced a vision which confirmed to him the same power of the imagination that Stevens was evoking when he quoted the later poem on London.

At the end of The Prelude, his poetic autobiography, Wordsworth sees both the darkness and light of human life at Stonehenge: first,

… the sacrificial altar, fed

With living men — how deep the groans! — the voice

Of those in the gigantic wicker thrills

Throughout the region far and near

“At other moments”, though, he writes

… I was gently charmed,

Albeit with an antiquarian’s dream,

And saw the bearded teachers, with white wands

Uplifted, pointing to the starry sky,

Alternately, and plain below, while breath

Of music seemed to guide them, and the waste

Was cheared with stillness and a pleasant sound.

The significance of the “three summer days” Wordsworth spent wandering Salisbury Plain is indicated by the subject of this section of The Prelude: “Imagination, How Impaired and Restored”. In his early twenties, following his return from revolutionary France, Wordsworth experienced a severe disillusionment with the world, precipitated by the violence of the Reign of Terror and the war between Britain and France. At Stonehenge, he has a vision of violence, but also of peace, both of which are characterised by poetry’s magic power: meaningful sound.

The vaguer side of the “antiquarian’s dream” is immortalised by the song “Stonehenge” from the heavy-metal mockumentary This is Spinal Tap (1984). The band perform it solemnly as a foam trilithon — rendered tiny due to the confusion of feet and inches — descends onto the stage:

No one knows who they were or what they were doing

But their legacy remains

Hewn into the living rock, of StonehengeStonehenge! Where the demons dwell

Where the banshees live and they do live well

In the twentieth century, serious poetic allusions to Stonehenge tend to emphasise its sheer solidity, making the stones a symbol of anti-modernity (“their stillness can outlast / The skies of history hurrying overhead”, wrote Siegfried Sassoon) or non-human temporality (considering “the constancy of things”, A.K. Ramanujan balances “Stonehenge or cherry trees” in a single line).

In “Channel Firing”, dated April 1914, Thomas Hardy heard preparations for war on the south coast:

Again the guns disturbed the hour,

Roaring their readiness to avenge,

As far inland as Stourton Tower,

And Camelot, and starlit Stonehenge.

It’s dazzling how, in this final quatrain, Hardy’s Wessex landscape leaps back through the centuries: from the eighteenth-century folly also known as “King Arthur’s Tower” to mythical, dactylic Camelot, until settling — in a poised image of peace — on the only English rhyme for “avenge” that is not “revenge”.

The way Hardy’s poem about noise of modernity falls silent as it reaches Stonehenge seems to foreshadow the way that expanding archaeological knowledge about the site has chipped away at confidence about its “meaning” over the last century. As Ronald Hutton has written: “a steady flow of exciting new information […] has not given us any better access to the ideas which inspired the monument; and therefore speculation about those can remain indefinite”.

For some modern poets, however, Stonehenge’s solid value in an age of information is as a symbol of the indefinite: the hope of what can be imagined. At the end of the Sixties, when theories that stone circles were astrological calendars or observatories were fashionable, J.H. Prynne dismissed what he saw as capitalist values projected backwards: “the middle-class merchant fingering his wrist-watch”. Instead, he urged in a lecture from 1971:

Think of the extraordinary unlikelihood of what such a thing like Stonehenge or Avebury were built to predict. They never thought they would work. Oh, never. I mean, they were chance shots. Like, sooner or later it must come round again, and it must come round again because it was wanted: and if it was wanted, it would come. There is this immense controversy now about how they knew over those immense periods of time that there were cyclic repetitions in the movement of heavenly bodies. They didn’t know. They just wanted it. That’s how it happened.

An absurd expression of this position comes in John Ashbery’s long poem Flow Chart (1990), where the world’s most famous stone circle functions as an ironic rhetorical full stop:

What people never really wanted to talk about—Stonehenge.

There are still poetic things to be said about the condition of not-knowing, though. In 2019, Will Harris spent time at Stonehenge as part of the Places of Poetry project, making verse from the words of English Heritage volunteers in a way that catches something memorably tentative about the imaginative experience of being among the stones:

You can read more here:

https://www.littletoller.co.uk/the-clearing/poetry/places-of-poetry-stone-circle-by-will-harris/

NOTES

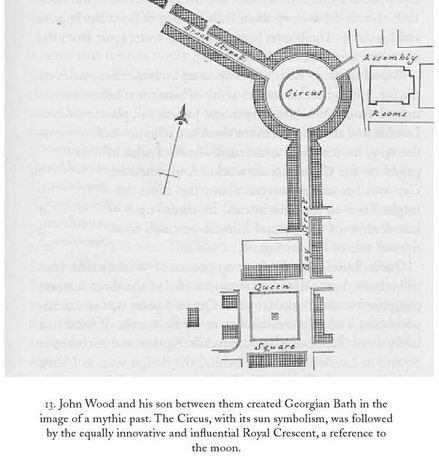

Stonehenge hasn’t only inspired poems. According to Rosemary Hill, it was also the model for the first British roundabout: the Circus in Georgian Bath, as designed by the architect John Wood, who based it on his study of nearby Stonehenge.

You can read J.H. Prynne’s lecture on Charles Olson, which concludes with his comment on stone circles, here:

http://www.charlesolson.org/Files/Prynnelecture1.htm

Spinal Tap, “Stonehenge”

Prynne starting a sentence with "Like," demonstrates once again how important he was to the cast and writers of "Friends"