This week I found myself talking about Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914) with both Poetry MA students and undergraduate Modernism students. It’s a great levelling book to teach, because it defies you to paraphrase it, while hinting at meaning in fascinating ways. For the undergraduates, I also gave a lecture on “The Pleasures of Modernism”, which circled around Stein’s answer, in 1934, to an American journalist who doubted her ability “to speak intelligibly”:

Look here, being intelligible is not what it seems. You mean by understanding that you can talk about it in the way that you have a habit of talking — putting it into other words. But I mean by understanding enjoyment… If you enjoy it you understand it… If you did not enjoy it, why do you make a fuss about it?

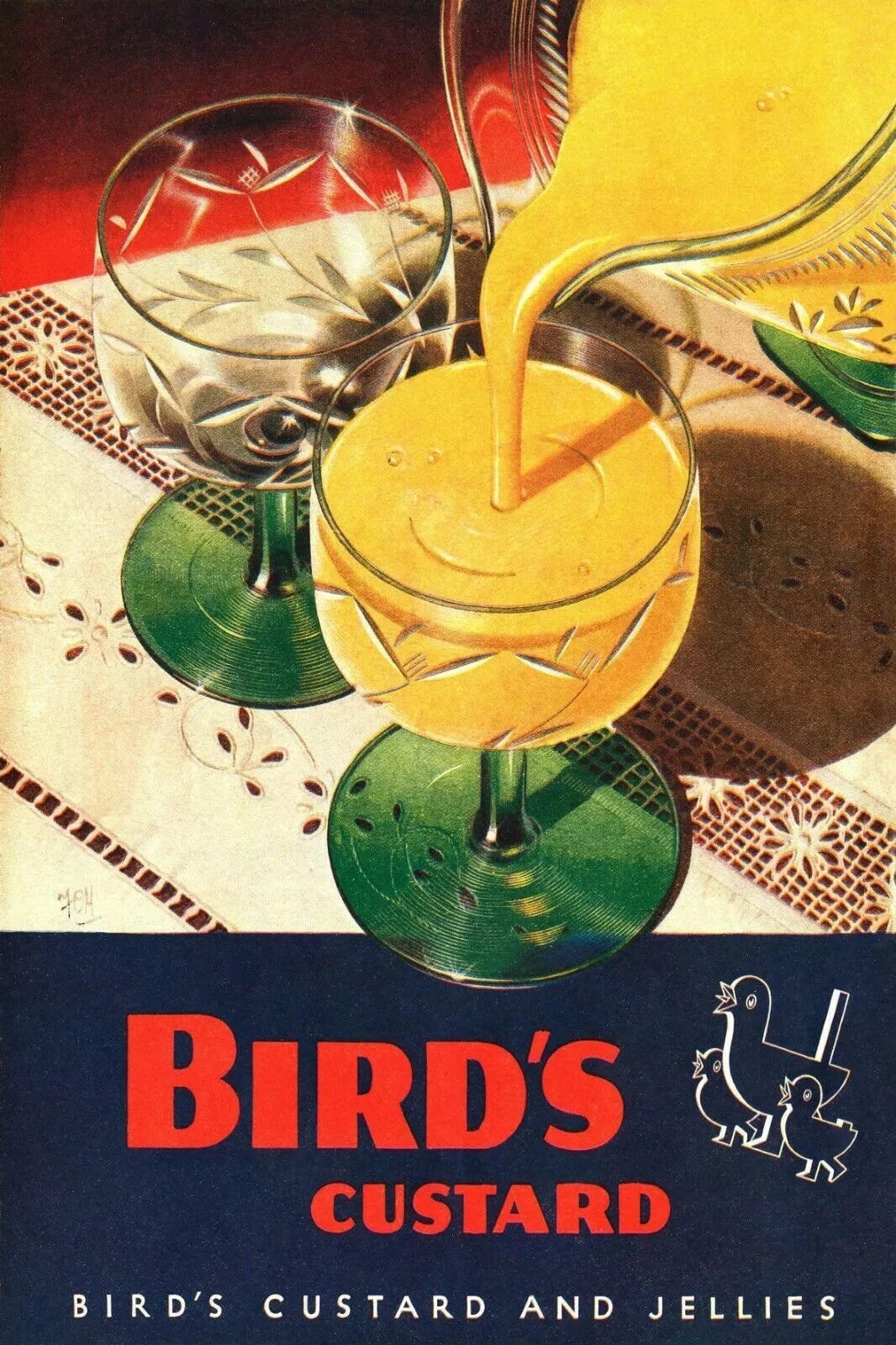

In my lecture, I try to square the circle of Stein’s argument by putting some of her writing “into other words”, while at the same time holding onto the idea that “if you enjoy it you understand it”. Every time I give this lecture I rewrite it, which partly reflects the way that Tender Buttons seems to rewrite itself before your very eyes (I once dreamed that I owned a pop-up version). A concluding discussion of the nature of custard, however, has been one of its constant features. Here’s my latest attempt.

When Gertrude Stein said “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose”, she meant it. She was trying to recover roses from centuries of literary symbolism, and she claimed that, in her line, “the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years”. How? Well, think about how the four roses in Stein’s line aren’t necessarily the same — how a “rose” can be a shade of red, or a woman’s name, or even the past participle of the verb “(a)rise”. Think also how a rose itself is a repetitive, circling structure.

The point of the line is that it unfixes the rose from any single point of interpretation. Stein is asserting the beauty of seeing roses as roses. The poet Mina Loy expressed this idea more broadly in an essay from 1924, when she argued that

Modernism has democratized the subject matter […] of art; through Cubism the newspaper has assumed an aesthetic quality […] Gertrude Stein has given us the Word, in and for itself.

Would life not be lovelier if you were constantly overjoyed by the sublimely pure concavity of your wash bowls? The tubular dynamics of your cigarette?

What does Loy mean here? The newspaper, she says, has been aestheticised by Cubism, the Modernist movement in painting with which Stein was closely associated. What does a Cubist picture look like? Here is one by Georges Braque, a close friend of Stein, called “Violin and Pipe”, which shows how Cubism brought newspaper (a product of mass culture) into painting: not by painting it, but by collage. Braque has actually stuck pieces of the French newspaper, Le Quotidien (which means “the daily, the everyday”) into his picture. What effect does this have on us as viewers? Well, we might notice how the printed “Q” of Braque’s picture is echoed in the stylised shapes of the faintly sketched violin and the pipe (also cut out of newspaper); he makes an association between the familiar kinds of pleasure we get from these objects and the often-overlooked, everyday pleasure of a well-designed typeface.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.