This week, at a poetry reading, I heard something that — as a poetry reader— genuinely intrigued me. The poet was reflecting on how there are no rules about where to break the line in free verse. Sometimes, said the poet, I adjust the margin in the Word document to see what difference it makes. Other poets in the room nodded in recognition; one compared it to turning a painting upside down to assess the composition. Adjusting the margins, I realised, was a thing.

I’ve been thinking about this ever since, because it gave me an insight into something which is a question for any reader of poetry. When I wrote last week, in my post about iambic pentameter, that

Many readers will hear a slight pause at a line break, marking its measure

I was consciously hedging on a potential controversy. Many critics would insist on pausing to observe the significance of the line break, whether a poem is read with the eyes or the mouth. Edna Longley, for example, believes that

Line-endings mark a pause, a briefly heard silence, a drawing of breath, a taking of bearings

My own feeling, however, is: maybe. A marked pause may be appropriate to some kinds of free verse, where the poet clearly intends enjambment as a sort of emphatic baton, heightening the meaning of each word it touches — for example, Geoffrey Hill’s The Triumph of Love (2000), here defining poetry as a sad and angry consolation in three slightly different ways:

But in many other poets, the use of line breaks is more like the freehand marks of a visual artist: en masse, they create a space within which the poem happens.

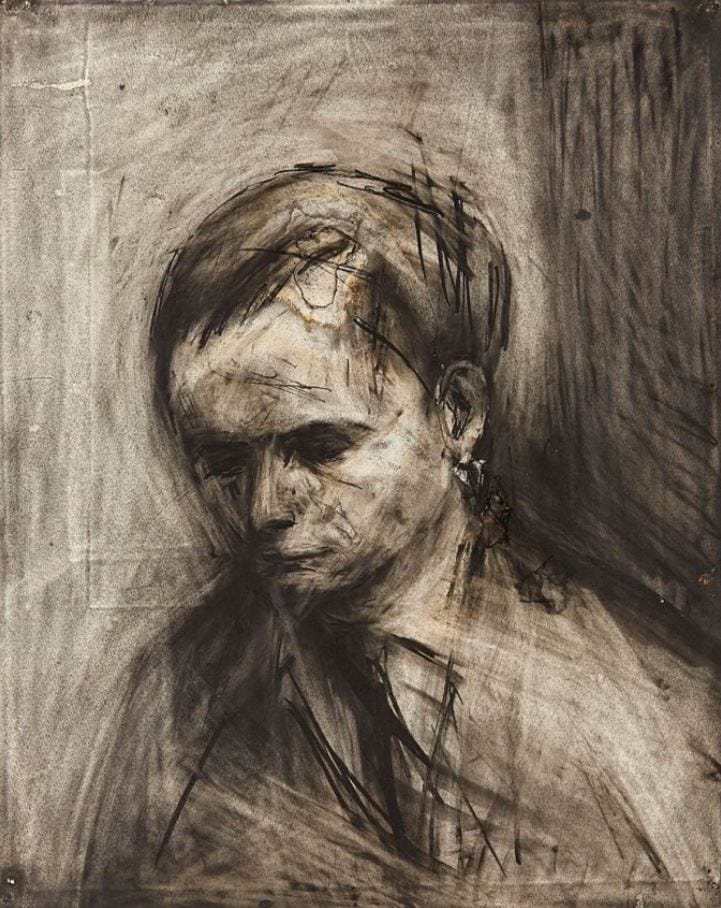

I was thinking about this the next day as I looked at an early portrait of Leon Kossoff by Frank Auerbach, which I am lucky enough to be able to do on my lunch break at the University of East Anglia. In Auerbach’s chiaroscuro, where chalk and charcoal rough out light and shadow, the sitter drifts between definition and dissolution:

Auerbach’s picture is built up out of visible rubbings-out (the wound-like patch on the top of the head is a break in the paper) and equally visible markings-in (the exact black curve of the nostril). The whole thing is a miracle of human likeness emerging from a world of smoke, like the moon from behind a cloud (Auerbach once said: “I wanted to make a painting that, when you saw it, would be like touching something in the dark”). There is a sense of lines erased and revised, repeatedly, until just right.

I get a similar feeling of controlled fragility from the poems of Marianne Moore, with their hairline-fracture line breaks. In the mirrored stanzas of the following poem, a repeated syllabic pattern — 7 / 8 / 6 / 8 / 8 / 5 / 9-10 — emphasises overall shape rather than individual enjambment:

Signalling her interest in bringing verse close to prose, Moore begins by taking a sentence from the New York Times and breaking it at “the”. She then takes the iambic lilt of her title (“No Swan So Fine”) and breaks it with an unlilting description of a real swan (“with swart blind look askance / and ambidextrous legs”). The rest of the poem builds the brittle, lyrical image of the china swan perched on the “branching foam” of the florid candelabrum — until the last sentence makes a “dead fountain” of this too.

All the line breaks feel pointed, but none are emphatic, even the faint rhyme pairs of “swan/fawn-”, “-comb/foam”. Moore’s syllabic enjambments are a stilling of significance. And thinking about the mutings of Moore — and the revisions of Auerbach — helps me to understand the compositional practice of adjusting the margins in a Word doc: rather than reading a line break as an audible pause, a meaningful emphasis, we might see it as a silently shaping mark.

NOTES

There are a range of critical readings of Moore’s “So Swan So Fine” here:

http://maps-legacy.org/poets/m_r/moore/swan.htm

You can read more about Frank Auerbach’s portrait of Leon Kossoff here:

https://www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk/art-and-objects/38-portrait-of-leon-kossoff/

I wrote a little bit about Moore’s use of “light or inconspicuous rhyme” here:

The Raw Material of Poetry

This week began, like every autumn term in recent years, with a discussion of Marianne Moore’s “Poetry” (1919). As ever, my new MA students had new insights into this poem about poetry which begins — notoriously, awkwardly — “I, too, dislike it”. (If you don’t know the poem, you can read / like / dislike an annot…