Welcome to Pinks 11, which is also the last post from Some Flowers Soon this year. Thanks to everyone for reading, and a special thanks to everyone who has become a paid subscriber since the summer — it’s really helped to keep the show on the road. Your messages have been much appreciated too. If you’re a free subscriber and want to catch up on all posts this year, trial subscriptions begun in December will last for one month.

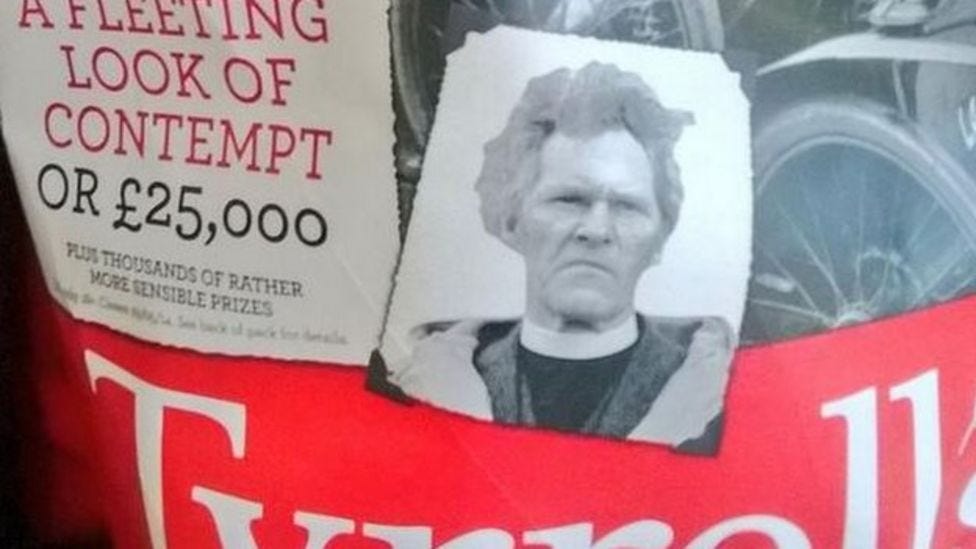

I’ll be back in January with a post to mark the tenth anniversary of Welsh poet R.S. Thomas appearing on a packet of crisps, plus an Alternative T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist. Until then, here’s some winter reading and a thought about the poetry of carols… Comments welcome.

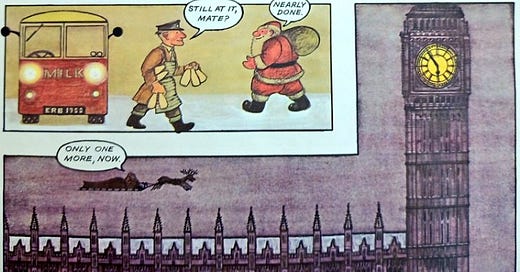

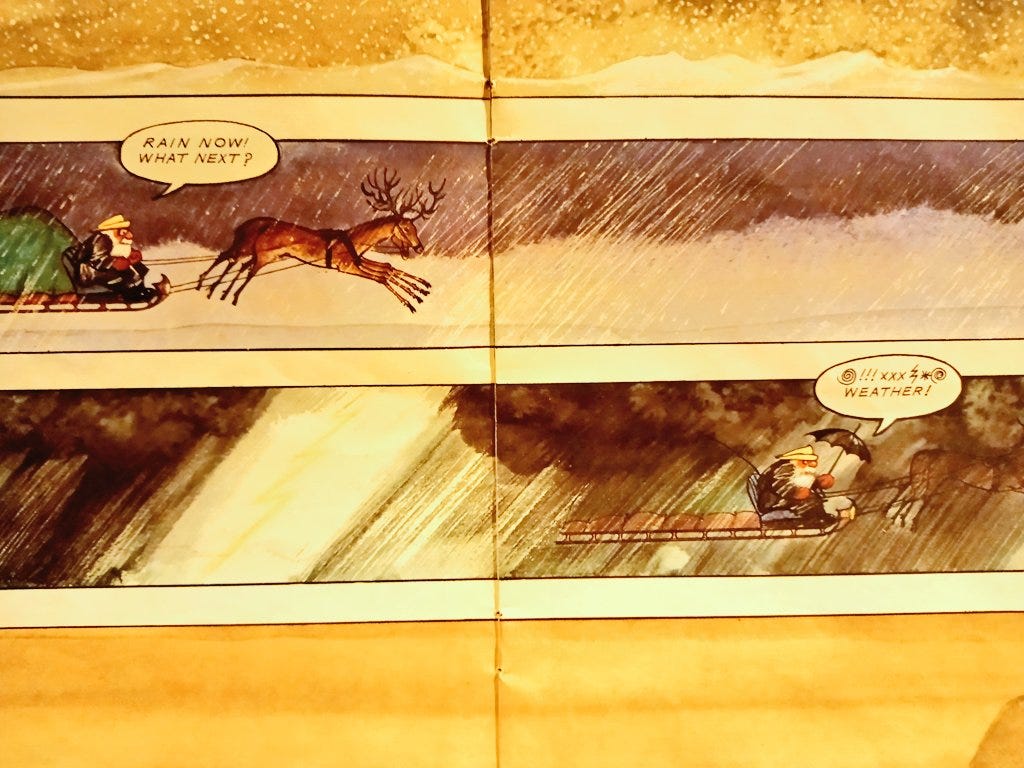

Here, just published, is an appreciation I wrote of Raymond Briggs’ Father Christmas (1973), to mark the 50th anniversary of this Christmas picture-book masterpiece:

Incidentally, if anyone knows where the curious passage about “ye lost and lamenting hounde” comes from, let me know — I can only find it in Christmas anthologies!

A seasonal essay I enjoyed this month was Victoria Moul’s illumination of the lost habit of writing Nativity poems in Latin. They might have begun as academic exercises, but sixteenth-century English scholars could describe wintry cold with the passion of personal experience:

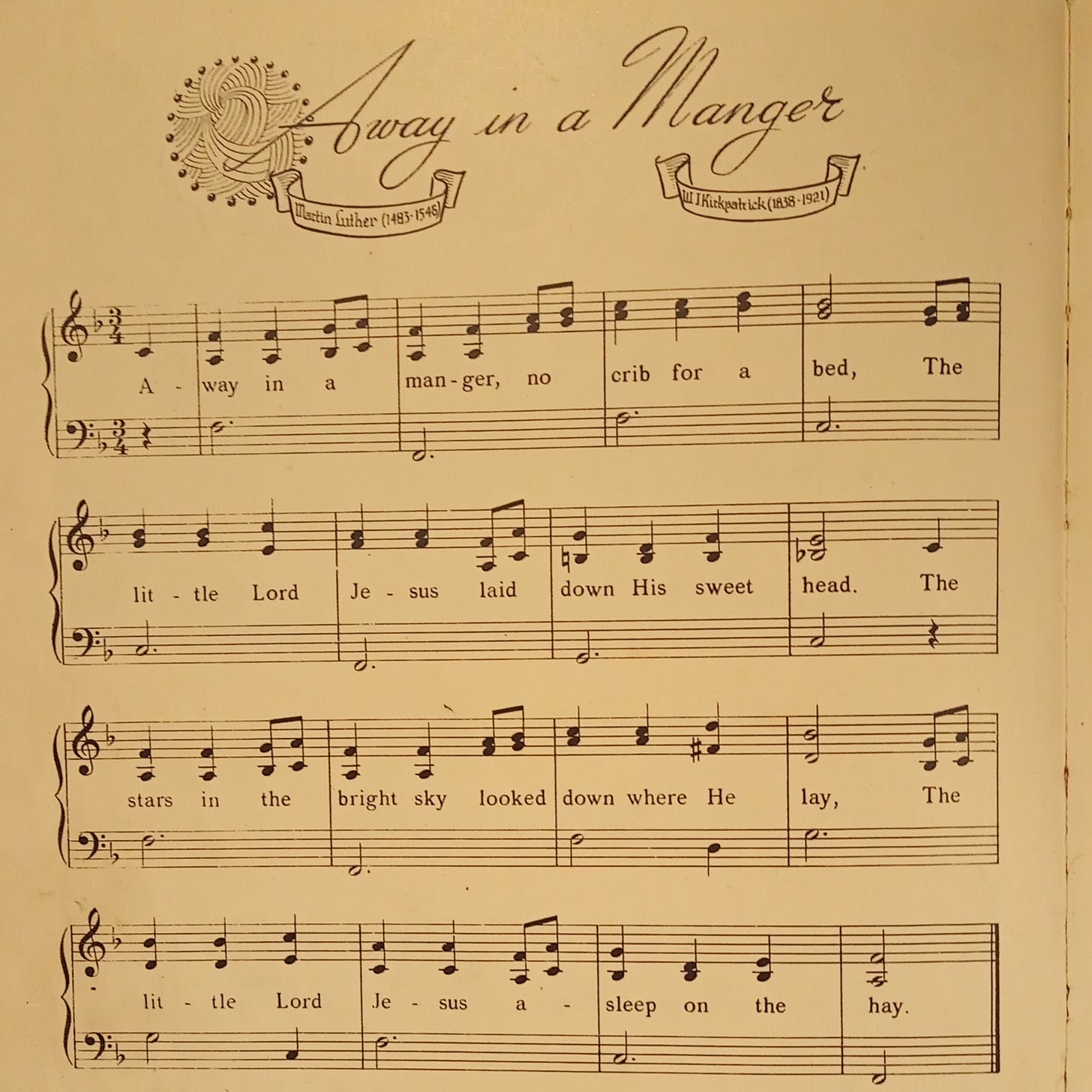

And finally: around now, I find myself thinking about the strange poetry of prepositions in Christmas carols. They remind me of William Empson’s remark in his Seven Types of Ambiguity: A Study of Its Effects in English Verse (1930):

The English prepositions […] from being used in so many ways and in combination with so many verbs, have acquired not so much a number of meanings as a body of meanings continuous in several dimensions

In carols, prepositions often come to prominence as a rhyme word. “O Little Town of Bethlehem”, for example, has “The silent stars go by”, in order rhyme with “lie” (“O great classic cadences of English poetry”, quipped Denise Riley, “We blush to hear thee lie”). Or there is the reef-knot-like syntax that ends “Once in Royal David’s City”, which I always find unfortunately comic when it pulls tight:

Where like stars His children crowned

All in white shall wait around

— as though they were scrolling on their phones, wondering when dinner will be ready. And then there is Christina Rosetti’s great Zen line

Snow had fallen, snow on snow, snow on snow

in which “o” and “n” turn over like a snow globe.

But the one that gets people talking on social media every year (previously, Twitter; this year, Bluesky), is this:

The answers I’ve had are subtly various — asleep; safely stowed; over there; far distant; out of sight; on the road; at the back of the inn — and taken together illustrate how poetic effects are created by fine gaps of association around and between words. (And, speaking of rhyme, the echoic return of “away” in “the hay” at the end of the first verse is a nice verbal harmonic.) Further suggestions welcome. For now, that’s me away.

Lovely seasonal offering.

I like to think that it was originally a Geordie carol and “away in a manger” is broadly celebrative or as the dictionary puts it “(Tyneside) A general cry of encouragement” as in Howay the lads!

From Father Christmas to the strange use of prepositions in carols - this Christmas issue illustrates the range of your newsletter beautifully. Happy Christmas!