The rich junk of life bobs all about us: bureaus, thimbles, cats

Sylvia Plath, “A Comparison” (1962)

For admirers of Sylvia Plath, the first days of February are a melancholy anniversary: according to the dates given on her drafts, we know that between 1st and 5th February 1963 she wrote the last six poems of the amazing, sustained streak of inspiration that produced Ariel (1965). On 11th February 1963, she killed herself.

A comment I heard in a lecture as a student has always stayed with me: we don’t know whether Plath’s “last poem” was the cold tragedy of “Edge” (“The woman is perfected / Her dead // Body wears the smile of accomplishment”) or the domestic comedy of “Balloons”, since both are dated 5th February. But we may be losing sight of something important if we assume — as many biographers and critics have done — that it was “Edge”, and read Plath’s life and writing as leading inevitably to that end.

As Marjorie Perloff argued in “The Two Ariels: The (Re)marking of the Sylvia Plath Canon” (1984), Ted Hughes — Plath’s estranged husband and posthumous editor — ended the first published edition of Ariel in a way that suggested her “suicide was inevitable”: the last three poems were the bleak trio of “Contusion”, “Edge” and “Words”. Yet Plath compiled the original Ariel manuscript before writing these last poems, and closed it with the more hopeful “Wintering”, which ends with a vision of women surviving, bees flying, and the word “spring”.

“Balloons”, in Hughes’s Ariel, was sixth from the end; you can read it here. The following notes suggest how it might be seen as an equally important and positive statement of Plath’s poetic vision as “Wintering” — a vision that, had she lived, she might have pursued well into our own time (her generation produced many octogenarian poets, and her centenary is still eight years away). That’s another melancholy thought — but “Balloons” is not a melancholy poem.

Globes of thin air, red, green

“Balloons”, to state the obvious, is about balloons: specifically, the kind of cheap, colourful rubber balloons that became popular party toys and decorations in the twentieth century — the sort you blow up and tie off round your finger (and not, as one critic oddly suggests, helium balloons). As far as I’m aware, this in itself is a claim to distinction: Sylvia Plath wrote the first (and only?) great poem about party balloons in English.

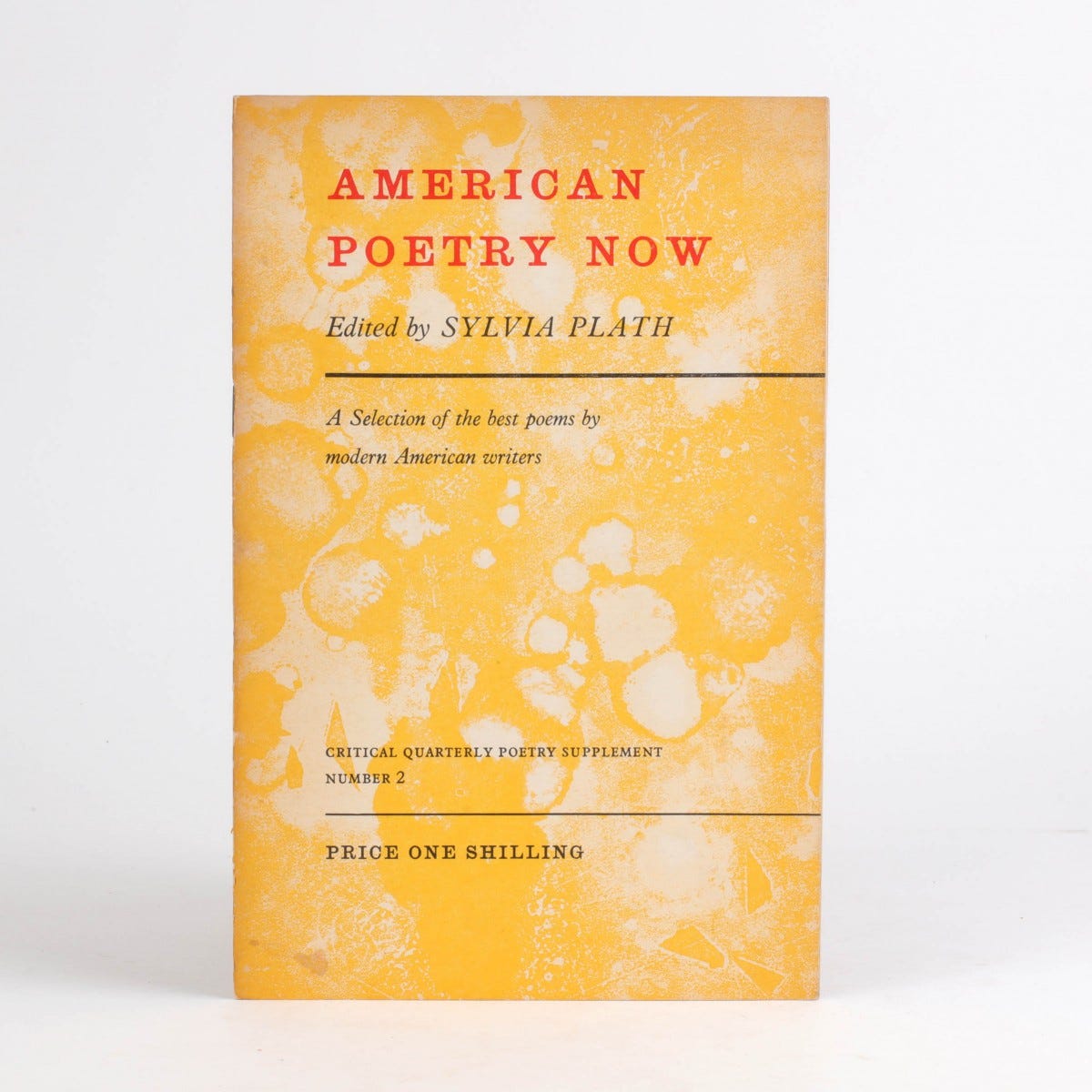

Plath left relatively few critical statements about what she valued in poetry. Her introduction to American Poetry Now, a pamphlet of poems that she compiled in 1961, simply reads: “I’ll let the vigour and variety of these poems speak for themselves”. But her short essay, “A Comparison”, broadcast on BBC radio in July 1962, gives a clue to one of her particular preoccupations. “How I envy the novelist!” it begins:

To her, this fortunate one, what is there that isn’t relevant! Old shoes can be used, doorknobs, air letters, flannel nightgowns, cathedrals, nail varnish, jet planes, rose arbours and budgerigars; little mannerisms — the sucking at a tooth, the tugging at a hemline — any weird or warty or fine or despicable thing.

Plath envies the novelist — pointedly gendered as female — because she can include so many more everyday things in her books than “the smallish, unofficial garden-variety poem”: “I have never put a toothbrush in a poem”, she laments. So it is notable that the smallish poems she selects to represent “American Poetry Now” include a dramatic monologue by Howard Nemerov in which an old widower contemplates a vacuum cleaner: “its bag limp as a stopped lung, its mouth / Grinning into the floor”.

The poem is about grief: the old man imagines that “when my old woman died her soul / Went into that vacuum cleaner”, and recalls how its bag would “swell like a belly […] and begin to howl” when full. It ends with an image of “the hungry, angry heart” which also “howls, biting at air”.

I hear several light echoes of Nemerov’s “The Vacuum” in the way that “Balloons” anthropomorphises its homely “soul-animals”, which somehow loom larger in the speaker’s mind than in reality (“Taking up half the space”). The balloons also have an alarming voice, making themselves known with a “shriek and pop” — and at the end of Plath’s poem, when the balloon bursts, we have an image of “biting at air”.

But the echoes are also an inversion: from the point of view of physics, a balloon full of air is the opposite of a vacuum; the balloons do not anger but delight “the heart”; and the poem is spoken not by an old man grieving for his wife but a young woman taking care of small children. Although we may know from Plath’s life that an implicit context for the first line of “Balloons” (“Since Christmas they have lived with us”) is the absence of Hughes, who does not live with his family, the poem does not tell us that. Instead, it resembles the image for poetry that Plath offers in “A Comparison”:

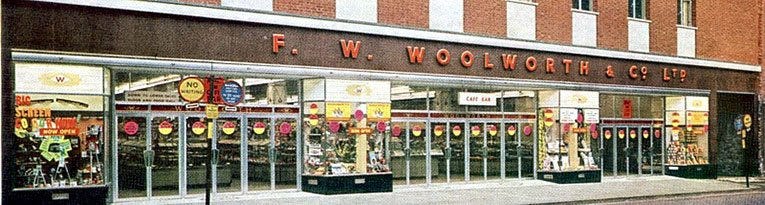

Those round glass Victorian paperweights which I remember, yet can never find — a far cry from the plastic mass-productions which stud the toy counters in Woolworth’s. This sort of paperweight is a clear globe, self-complete, very pure, with a forest or village or family group within it.

“Balloons” takes the cheap toys — very likely bought at Woolworth’s — that as a single parent Plath has allowed in the house for over a month to keep her children amused (struggling to arrange childcare was a constant issue) and transforms them into the “clear globe” of a “self-complete, very pure” lyric poem. The poem is the better present, the lasting toy. As she wrote at the end of “Morning Song”, her ecstatic lyric about a newborn baby, written two years earlier, and placed first in her Ariel manuscript: “The clear vowels rise like balloons”.

If “Balloons” offers a vision of what poems themselves can make out of breath, this has implications for the final stanza, in which the baby boy — seeing “A funny pink world he might eat” — bites and bursts one:

Then sits

Back, fat jug

Contemplating a world clear as water.

A red

Shred in his little fist.

Is it a moment of disillusionment, an admission that poems can’t sustain the “funny pink” (or, we might say, rose-tinted) world that they create? Clearly the sadness of this is one reading. But just as the poem excludes the bang of the balloon bursting, it also stops before the tears that will inevitably follow: for a moment, the “fat jug” of the baby has not spilled, even though the next line (“Contemplating a world clear as water”) suggests there are tears in his eyes. The way Plath tells the image, with its tone of tender humour, foreshadows the parental soothing that will follow. But there is also, for the poet, a note of triumph: a new poem, the first in the world, has recorded the reality of what happens when you give a baby a balloon (“sits / Back” implies that he was previously sitting forward, pressing his face right into the squishy thing). “A poem is concentrated, a closed fist”, writes Plath in “A Comparison”. And to a would-be poet who wrote to her in November 1962, asking for advice, she replied:

Let the world blow in more roughly […] You should give yourself exercises in roughness, not lyrical neatness. Say blue, instead of sapphire, red instead of crimson.

That “red / Shred” — an example of the kind of emphatic “hammer rhyme” that Plath’s later poems delight in (see also “Back, fat”) — is a symbol of the lyrical roughness that she sought to “let the world blow in”. To quote Andrew Shields, who wrote in PN Review 131 about the possibility that “Balloons” was Plath’s last poem:

This final punch, like the poem as a whole, has its violence, but it is neither suicidal nor distant. It is the red violence of life, of the breath which filled the balloons

As Will May notes in a thoughtful essay on “Dickinson, Plath, and the Ballooning Tradition of American Poetry” (2017), balloons are important to two of Plath’s favourite characters from children’s literature: Mary Poppins and Winnie the Pooh . The A.A. Milne story that introduces us to Pooh features the bear attempting to use a balloon to deceive bees and get his favourite food, honey, by pretending to be a cloud. It doesn’t work, and Christopher Robin has to rescue him by shooting the balloon down, which leaves the bear’s arms

so stiff from holding on to the string of the balloon all that time that they stayed up straight in the air for more than a week, and whenever a fly came and settled on his nose he had to blow it off. And I think—but I am not sure—that that is why he was always called Pooh.

A burst balloon, in other words, can be a happy ending — and the beginning of more stories.

In the draft of “Balloons”, Plath cancels a line:

Boons, you say, boons, boons

The speaker is her nearly-three-year-old daughter, Frieda — the “you” to whom the description of the biting baby is conspiratorially addressed with the words “Your small // Brother”. As Nephie Christodoulides points out in her study Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking: Motherhood in Sylvia Plath’s Work (2005), this closely echoes a line from Ted Hughes’ poem “Full Moon and Little Frieda”, which had just been published in the Observer newspaper on 27th January 1963:

Moon! you cry suddenly, Moon! Moon!

Did Plath cancel the line because she realised it would be read as a parody of her husband’s — even if not intended as such? If so, it’s a pity that the poem lost the lovely “boons”, with its punning on phonetic toddler speech and the old-fashioned word for a benefit or blessing, beloved of poets who needed a rhyme for “moon” (Keats: “Such the sun, the moon, / Trees old and young, sprouting a shady boon”).

There is, I think, another male poet haunting “Balloons” whose presence is more welcome. The only stanza to leave the domestic setting is the fourth, which compares the way the balloons delight the heart to

… wishes or free

Peacocks blessing

Old ground with a feather

Beaten in starry metals.

There is a precision and beauty to this simile: a colourful peacock feather may be imagined falling to the ground with the same gentle momentum as a settling balloon. But otherwise, this grand image seems to have come from another poem entirely — specifically, I think, one by W.B. Yeats, about the satisfaction of capturing life in art:

What’s riches to him

That has made a great peacock

With the pride of his eye?

[…]

His ghost will be gay

Adding feather to feather

For the pride of his eye.

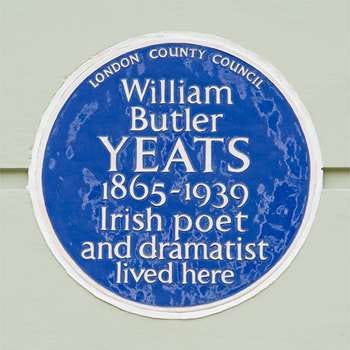

Famously, when Plath moved to London with her children in December 1962, the flat she found had a blue plaque over the door indicating that it had been Yeats’ childhood home (or “Old ground”). The feather “Beaten of starry metals” that floats into “Balloons” on 5th February 1963 feels like a “blessing” from the “free” ghost of the poet who wrote, in “Sailing to Byzantium”, of wanting to be immortalised through art, in “such a form as Grecian goldsmiths make / Of hammered gold” — and who Plath nominated, in a letter written on 4th February, as the “universal name for the lyrical”.

I want to give the last word of these notes on “Balloons” to Eavan Boland, who in her essay “Making the Difference: Eroticism and Aging in the Work of the Woman Poet” (1994) offers the most imaginatively and emotionally insightful reading I know of a poem that has often been neglected by critics seeking a more “fixed” reading of Plath:

[“Balloons”] occurs in an original and powerful sensory world, poised somewhere between treasure and danger. Obviously — since they are unconnected to a sexual perspective — the balloons are not erotic. Yet, as images, they operate in that territory where the strongest love poems take hold: where spirit and sense are seeking one another out […] Far from being possessed by the perspective which creates them, the balloons are set free within the poem as they might be outside it: to ride out a current of association and surrealism which ends in their destruction and the end of the poem. And the balloon which ends up as “a red shred” has had, by the end, a joyous, rapid mutation: has been a cathead and a globe, has been held by a child and has squeaked like a cat. Above all, it has not been fixed. The dominant impression left by the poem is of an imagination which has surrendered generously to the peril and adventure of the sensory moment.

NOTES

“A Comparison” and “Context” are both reprinted in Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams (1977). The quotations from Plath’s letters on poetry are taken from Heather Clark’s indispensable Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath (2020), and can be found under the entries in the index for “Carey, Father Michael”.

You can read Howard Nemerov’s “The Vaccum” here:

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42688/the-vacuum-56d2214e3c66c

For an illuminating post on Plath’s domestic life, including the insight that “Hughes complained bitterly about Plath needing four hours a day in which to write, and saying he had been generous in allowing her this time”, see:

I loved this reading of 'Balloons', particularly the vacuum-balloon connection! For me, the most curious thing about the publication/editing of Plath's poems is why no-one has ever collected the last poems, the ones Hughes seemed to think she was saving for a third book. This would include those last twelve poems from the completed 'Sheep in Fog' to 'Edge' and 'Balloons.' Given how Plath sells, why no last poems collection? I cannot understand it. It can be persuasively argued that we have the beginnings of what Plath’s intended as her third book -- a very different prospect to seeing them as a chunk of the Collected - why has this never been made available as a slim volume of its own? They are a hard-earned (See Hughes on the revisions of 'Sheep in Fog’) departure from Ariel and I think such a volume could change our reading of her work as a whole. That’s my (lengthy) two pennyworth, anyway. Cheers.

This is a lovely piece. There's another balloon in Winnie the Pooh – the present that Piglet gives Eeyore but excitedly bursts before he hands it over. Eeyore finds something to enjoy in what's left of it.