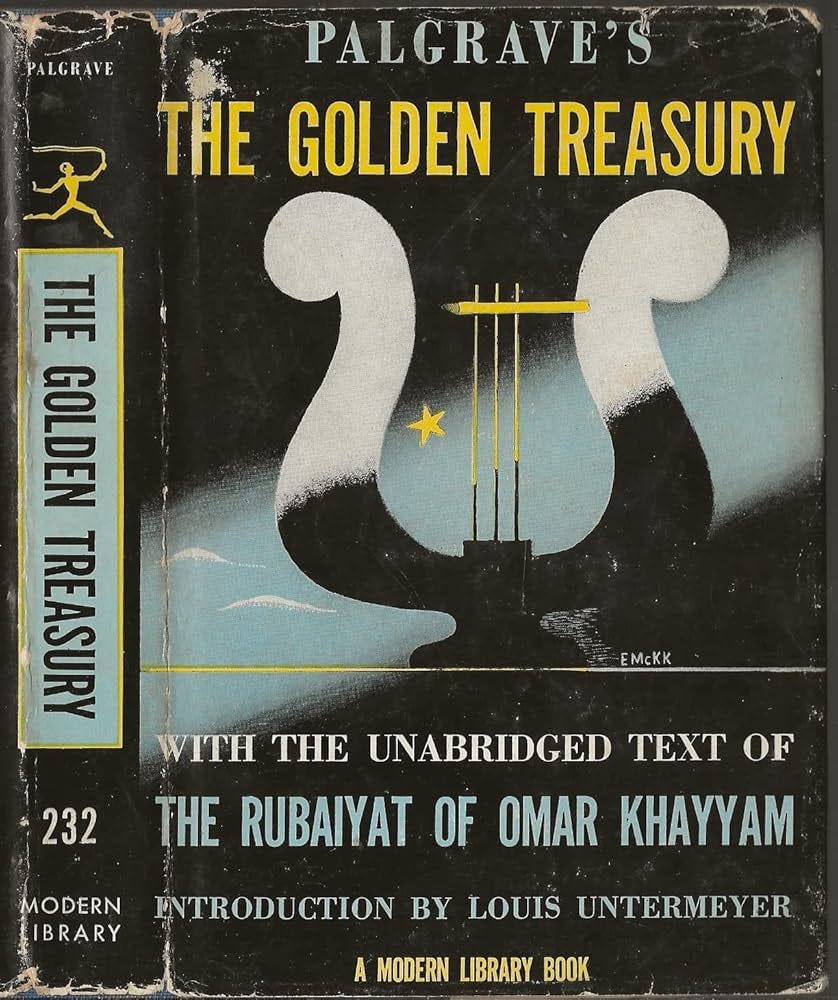

Pinks #22: A Golden Treasury Treasury

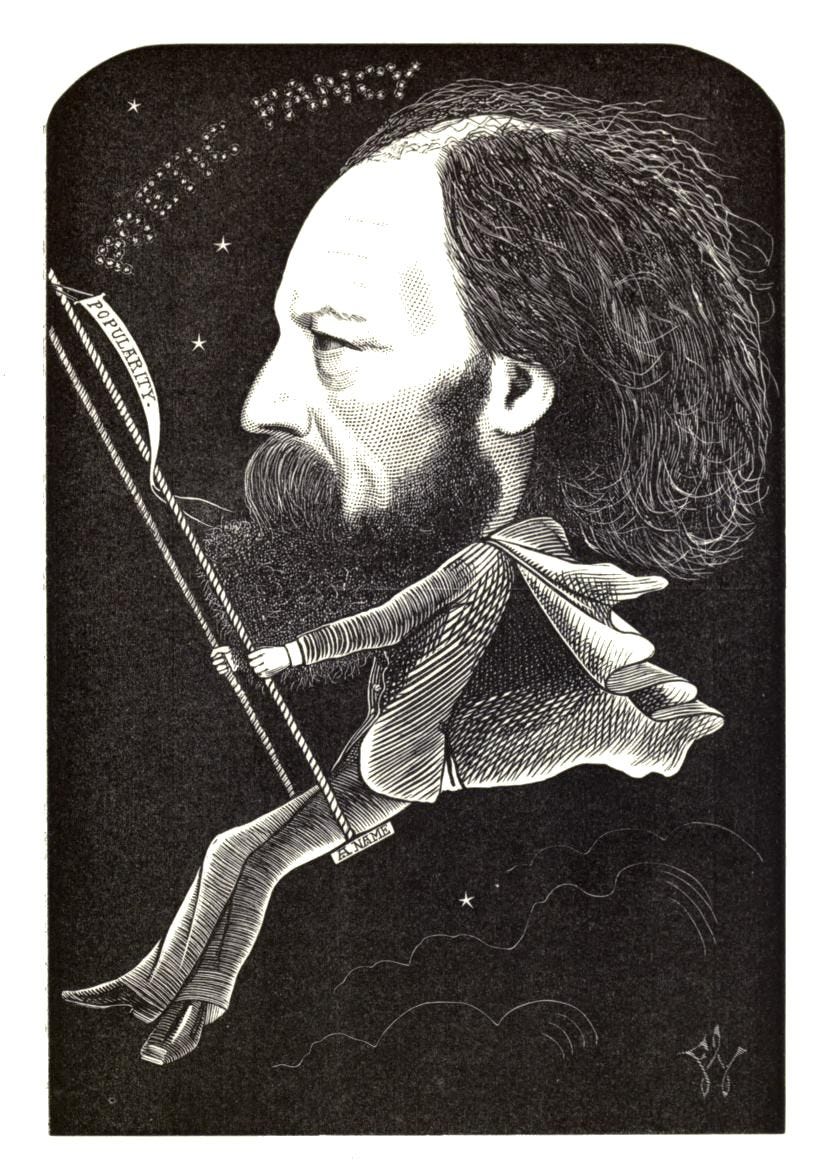

F.T. Palgrave, the most successful poetry anthologist ever

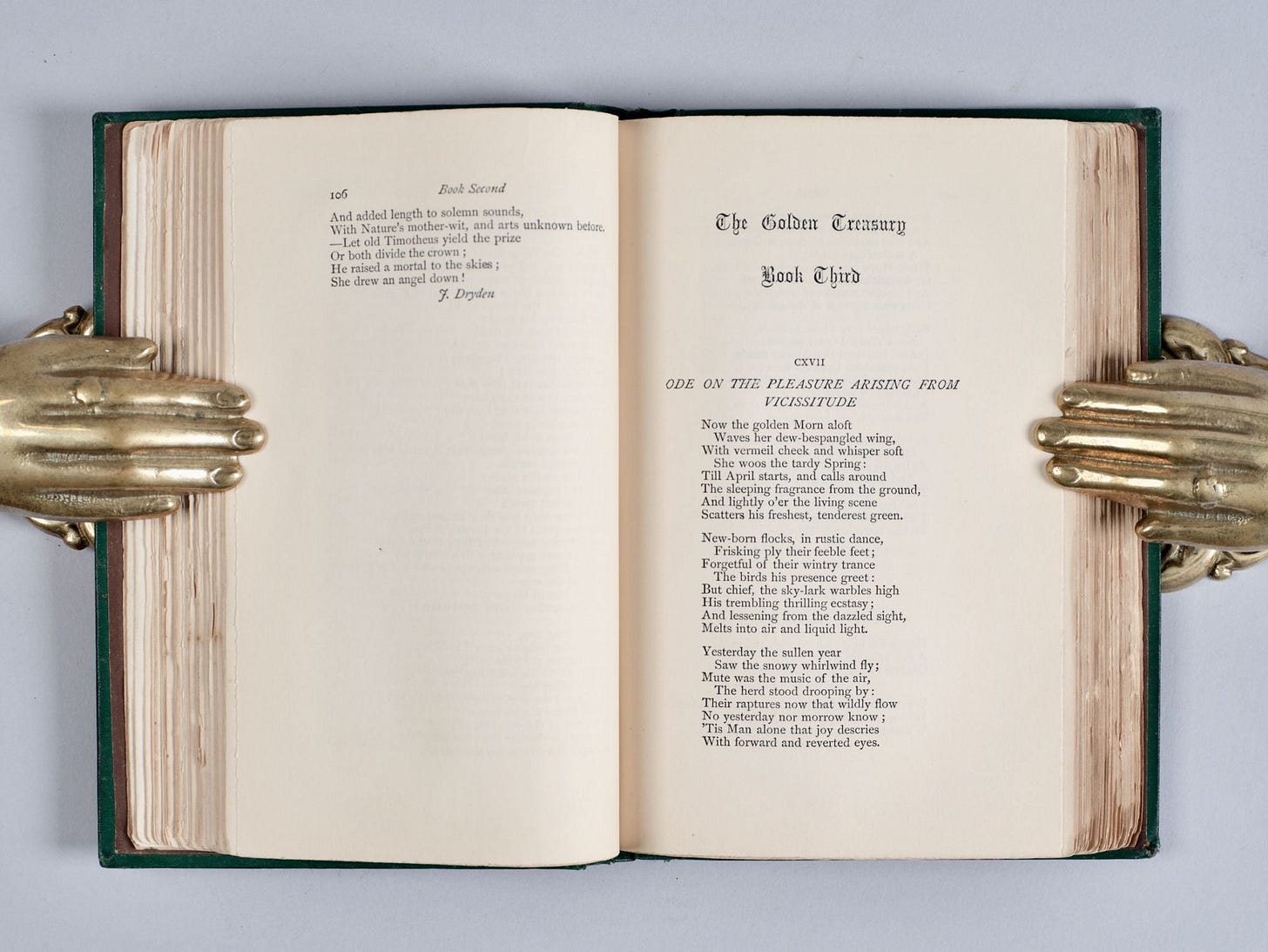

This little Collection differs, it is believed, from others in the attempt made to include in it all the best original Lyrical pieces and Songs in our language, by writers not living, — and none beside the best.

F.T. Palgrave, “Preface”, The Golden Treasury

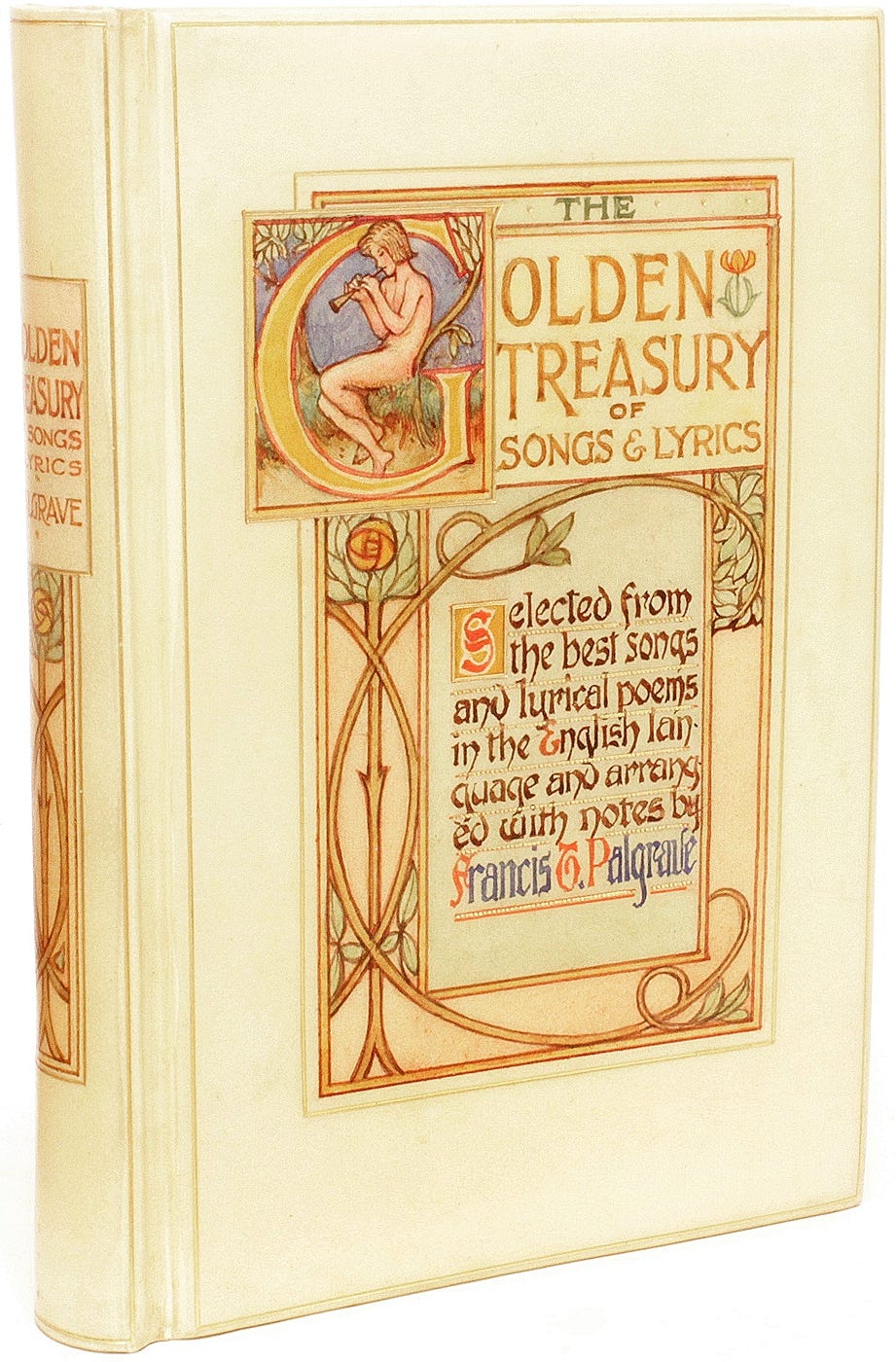

This weekend marks the bicentenary of one of the most influential editors in the history of English poetry: Francis Turner Palgrave. Born in Great Yarmouth, Norfolk, on 28th September 1824, he is remembered for an anthology that has never gone out of print: The Golden Treasury (1861) — or, to give it its full name, The Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English Language.

In The Treasuries: Poetry Anthologies and the Making of British Culture (2023), Clare Bucknell reports that a young Ezra Pound — with characteristic modesty — once approached a publisher with a proposal for a twelve-volume anthology “to replace that doddard Palgrave”. Unfortunately, the publisher Pound approached was Macmillan, whose fortunes rested significantly on the fact that they had published The Golden Treasury half a century earlier. It sold 10,000 copies in the first six months after publication, and by the Second World War more than 650,000 had been printed. The family money was inherited by Harold Macmillan, grandson of Macmillan’s founder, who became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. (Pound’s anthology never happened.)

Palgrave had an intensely high-minded early Victorian childhood. At three years old, his mother noted, with some disappointment, that he hadn’t yet learned to read:

Frank does not make a rapid progress in his book at present — he seems unable to understand that the letters are the symbols of the sound […] His memory is excellent, and he knows many little poems by heart.

At four and a half, he began to learn Latin vocabulary; by the age of ten he was memorising the first book of the Aeneid; and one of his favourite games to play with his brothers was to re-enact scenes from Homer. He also spent happy seaside summer holidays at Bank House, his grandparents’ home in Great Yarmouth. His daughter, Gwenilian, later remembered how

he was keenly alive to Nature’s sounds, and delighted in reading Lucretius or Virgil within hearing of a trickling stream or the breaking of waves on the shore

So it’s perhaps not surprising that his masterpiece was a book of poems to learn by heart. But the success of The Golden Treasury was also due to the rise of English Literature as an academic subject in the Victorian era, displacing the Classics at home and across the empire as a founding text of national identity and an instrument of soft power. Schoolchildren recited poems from Palgrave, and soldiers took him to the trenches. In Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter (1948), the British intelligence agent Edward Wilson reads poetry “secretly, like a drug”, carrying The Golden Treasury with him through colonial Africa, to be “taken at night in small doses”.

In his mid-twenties, Palgrave met Alfred Tennyson, and became a devoted friend of the future Poet Laureate. Tennyson wasn’t quite so devoted in return: on a walking tour of Cornwall in 1860, he complained in a letter that

All day long I am trying to get a quiet moment for reflection… but before I have finished a couplet I hear Palgrave’s voice like a bee in a bottle, making the neighbourhood resound with my name.

On the same trip, Palgrave first told Tennyson about his plan to make an anthology which would supersede all others by containing only the best lyric poems in English. Tennyson helped by advising on the selection, reading a draft version aloud to test each poem over the Christmas holidays in 1860. Palgrave wrote each expert verdict down.

Palgrave was also friends with Pre-Raphaelite painters and sculptors. Shortly after The Golden Treasury appeared, though, this got him into trouble. Commissioned to produce the Official Catalogue of the Fine Art Department of the International Exhibition of 1862, he took the chance to praise his friend, the artist Thomas Woolner, while rudely criticising other, more famous names. Letters were written to The Times objecting to his “discourteous tone” and “insolent language”. One correspondent even tracked down his London address, and discovered that it was the same as that of… Thomas Woolner, who, as Palgrave’s housemate, had suggested the title of The Golden Treasury and designed the frontispiece for the first edition (later used for the Penguin Classics cover, above).

Palgrave dedicated The Golden Treasury to Tennyson, with a note that ends in the hope that the book may prove “a storehouse of delight to Labour and Poverty”. This reflects the concern of his day job as a civil servant in the Education Department, whose first job was to train teachers to go into workhouses. The Golden Treasury aimed at, and reached, a working-class readership, by mixing popular songs and ballads with Shakespeare, Milton, the Metaphysicals (though not Donne) and the Romantic poets (though not Blake). Palgrave excluded “blank verse” as unlyrical, however, meaning that the book was entirely made up of rhyming verse — which I suspect may have influenced the enduring belief in Anglophone culture that poetry “ought to” rhyme.

You can read an excellent scholarly essay on The Golden Treasury here which explores, among other things, how Palgrave’s attention to detail helped to make his book a bestseller. It was his idea for Macmillan’s advertising to highlight the ongoing number of copies sold: 12,000 in August 1862, 14,000 in December 1862. And he even took pains over the paper it was printed on:

In letters of 24 January, 4 February, and [16 February 1861] he expresses concern about the paper, suggesting in the first that Macmillan try “some good French or German paper [...] because they are thin & unsized, qualities which make a book portable & clear in impression; & because I fear an English paper, at once thin & firm, is not to be had.” In the second letter he thinks “that the paper should be in tone about halfway between the piece sent, & pure white. It is now a decided buff — all one wants is a no-colour — a white subdued.”

The best poems in English were not to be displayed on a decided buff.

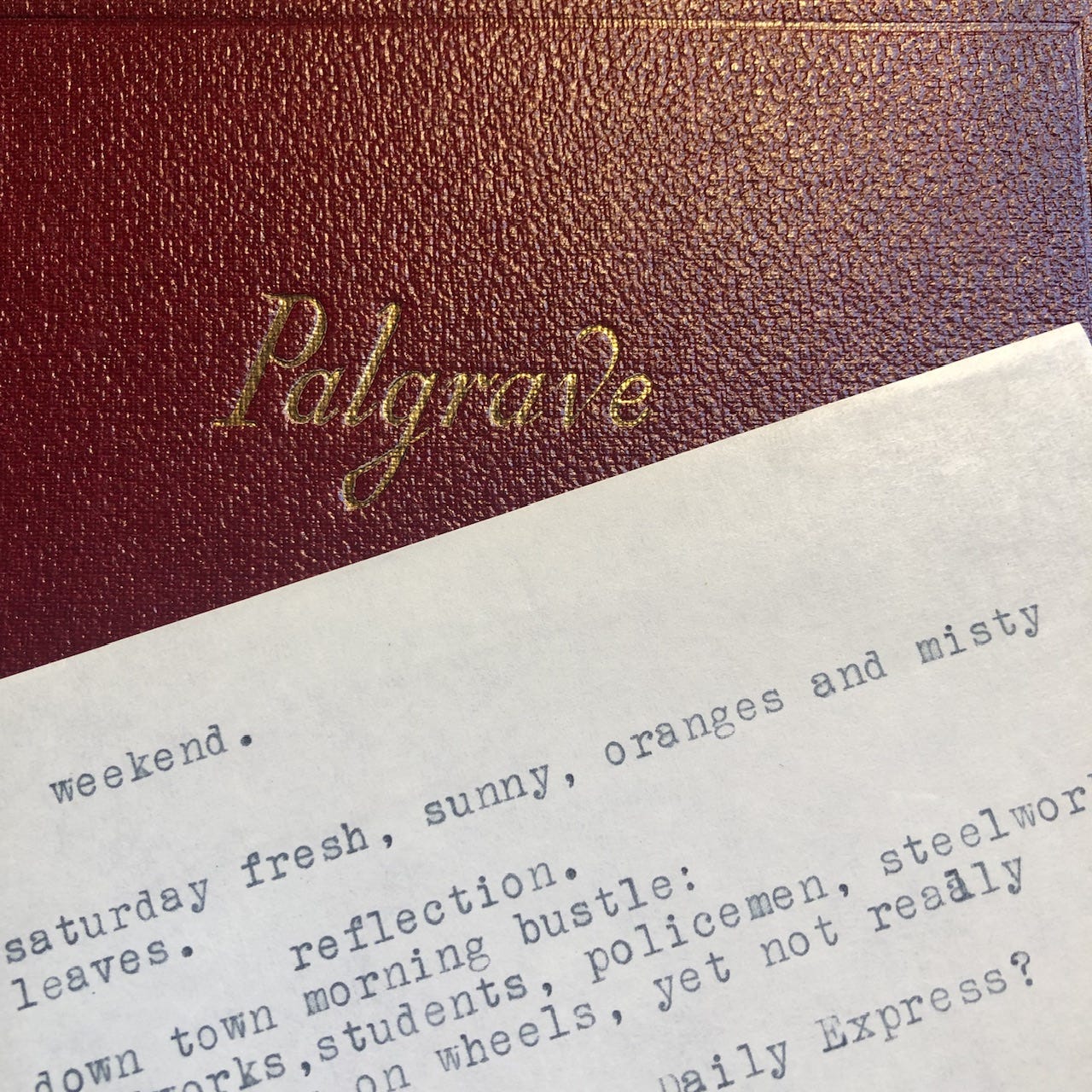

My copy of The Golden Treasury belonged to my Mum, who won it as a school prize. Tucked in the back is the only poem I’m aware that she wrote, typed in the all-lower-case lettering that was cool in the Sixties. It’s called “weekend”, it doesn’t rhyme, and I assume it dates from when she was studying to be a teacher in Sheffield, because it mentions the “morning bustle” of “students” and “steelworkers”. It ends:

smoky grey evening; the stone houses are dark and home.

monday…

It’s three years this week since I started writing Some Flowers Soon, and I’d like to thank everyone who has read and supported it along the way. These occasional Pinks posts are free, with full weekly posts for paid subscribers. If you’d like to become one of those, you can upgrade here:

I write these posts in the spare time I used to use for freelance reviewing, because I enjoy them much more than just passing judgement on books. As always, if you’re a student / precariously-employed academic / under-paid poet / reader of limited means, let me know and I’ll add you to the free list.

I shared this piece with my Mum, who was 91 on Wednesday. She learnt a lot of poetry by heart as a child, often from Palgrave, and can still quote reams of it. (She also, as a student, shared a stage at the Playhouse with Maggie Smith!). Mum says: Yes, I did enjoy this piece! I must say, the young Palgrave sounds a bit of a prig. it is very cheering that people still enjoy poetry in this tediously prosaic world.

Reading William Carlos Williams' semi-autobiography 'I wanted to write a poem' I noted how much he said he was influenced as a young poet by Palgrave. "The books that influenced me were my own discoveries. I knew Palgrave's Golden Treasury by heart." and then a few pages further on "The poems in this period, short, lyrical, were more or less influenced by my meeting with Pound, but even more by Palgrave's Golden Treasury. I was budding, had no real confidence in my power, but I wanted to make a poetry of my own and it began to come." Williams apparently conceptualises Palgrave as a whole, as he does Keats or Whitman - Palgrave is not portrayed as an anthology containing many different poets and approaches, but rather as a single poet with a style of his own.