“March” is a sharp word, brusque and bracing, like its month. “January”, “February”; they meander like rivers; “April” is like the sound of raindrops on the windowpane; but “March” is a gust of wind flinging grit.

Adrian Bell, 1 March 1958

The anniversary of the Covid lockdown in the UK last week took me back to this post about the poem that I thought of when it was announced: Edwin Muir’s “The Horses”.

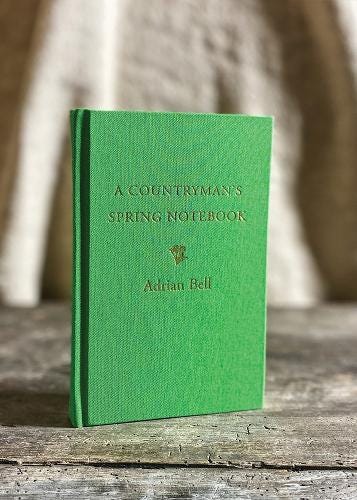

And thinking about the historic shift from horses to tractors took me back to Adrian Bell, one of my favourite writers about rural life. I first read Bell’s newspaper columns, “A Countryman’s Notebook”, in my local paper, the Eastern Daily Press, when they were being reprinted about fifteen years ago. The original series ran from 1950—1980, and seems to me one of the great literary achievements of the newspaper column as a form — perhaps not to be compared with Baudelaire’s feuilletons, which became the “little poems in prose” of Paris Spleen (1869), but an enduring contribution to the art of the sentence nevertheless, written with a poet’s feeling for words.

One thing I enjoy about “A Countryman’s Notebook” is how many light-hearted allusions to English poetry Bell manages to work into a column ostensibly about life in the Suffolk countryside, to be read over East Anglian breakfast tables each Saturday morning. As he told his life story, at the age of sixteen he read Tennyson’s lines about “The moan of doves in immemorial elms / And murmuring of innumerable bees” and decided to dedicate himself “to the plough and poetry”. His allusions are often to such Golden Treasury-style touchstones, but his range is wide. In April 1965, for example, he begins a column by quoting Henry Reed’s World War Two poem about being trained to use a rifle (“this is the piling swivel, / Which in your case you have not got”):

But how many BBCs are there? […] I reminded rather of that poem called “The Naming of Parts”. There is BBC 1; there is BBC 2 “which we have not got”.

The joke was that the BBC 2, launched in 1964, could only be watched on more up-to-date TV sets, which were presumably in short supply in Suffolk in 1965.

The tone of Bell’s newspaper columns is gentle and homely, but he had a quick wit, and said of his writing that he wanted “to put into words the way unrelated things came together and formed a relation” — a well-considered definition of the poetic impulse (compare T.S. Eliot in “The Metaphysical Poets” (1921) on how, “a poet’s mind […] is constantly amalgamating disparate experience”). In the same year as he published Corduroy (1930), his first autobiographical book about farming, Bell also set the first Times crossword, which he said was “the ideal job for a chap with a vacant mind sitting on a tractor harrowing clods”. He continued to set Times puzzles throughout his life; classic clues include “This cylinder is jammed” (5, 4). The answer appears in this Surrealist painting from 1939 by the poet Humphrey Jennings:

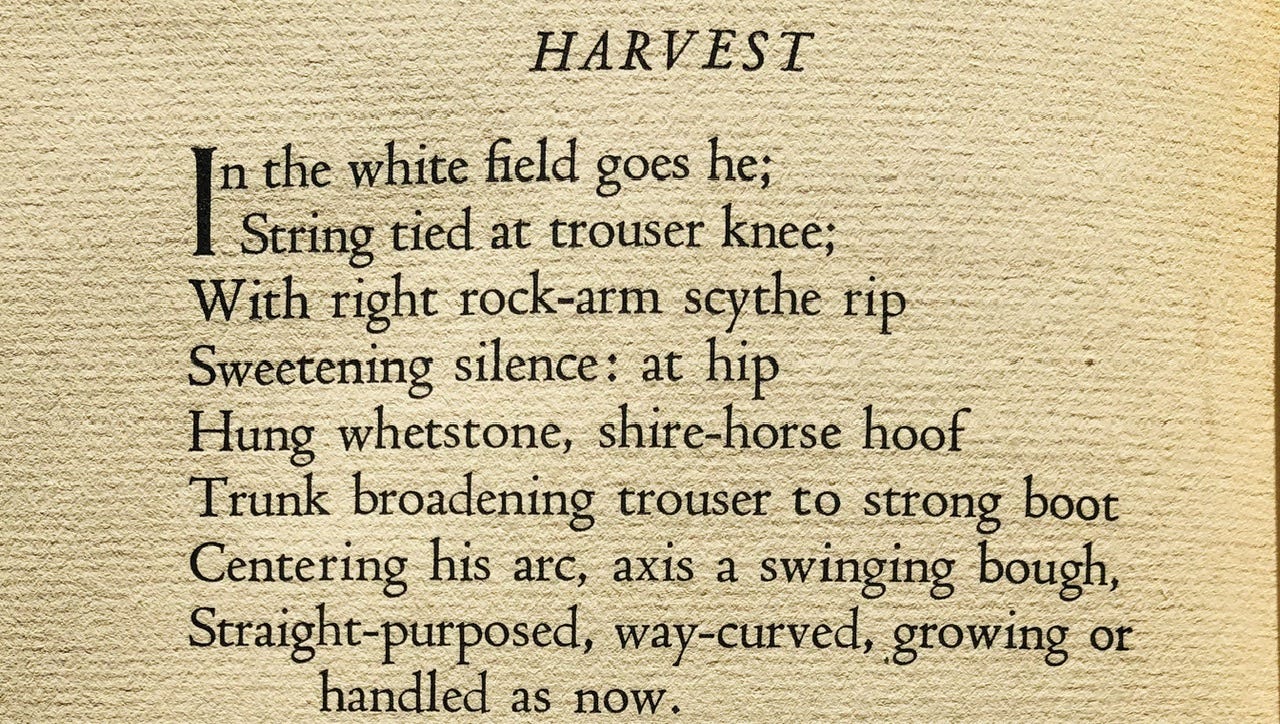

For all the poetry in his head, however, Bell only published one book of verse, Poems (1935), which epitomises the “slim volume” in its generous spreading of 14 poems over 23 pages. Like other English poets of his generation, Bell was influenced by two Victorians who became honorary moderns: Thomas Hardy, who lived until 1928, and Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose experimental prosody was only appreciated after the posthumous publication of his poems in 1918. Bell’s poem “Harvest” echoes the heroic magnification of the farm worker in “Harry Ploughman”. Compare the bodily solidity of Hopkins’ “Hard as hurdle arms” and “Rope-over thigh; knee-nave; and barrelled shank” with Bell’s “shire-horse hoof / Trunk broadening trouser to strong boot”, which blends the tapering shapes of man and animal:

But it is easy to get carried away by Hopkins’ sprung rhythms and percussive rhymes, as Bell does in the next sentence, when he describes scything by hand:

Mind no more daunted than young shoots that swerve

Round irremoveables, makes life’s curve serve

To sever at the base and lay all trim

With “curve serve / To sever” the crossword setter takes over, playing with words more than the poem needs. There are no wholly successful pieces in the book, but there are flashes of phrase and image that show Bell’s talent for resonant word-painting: “the hound insouciant / Shadowed fantastic on sunrisen frost”; “that sliced stack bright and blind”; “hay swathed over the graves”.

Reading Bell’s promising but stilted poems has left me with an even greater appreciation of how he wrote about the same subjects so warmly, thoughtfully and naturally for the local newspaper reader, perfecting an erudite but friendly voice whose verbal ingenuity is gently tamped down below the surface of each sentence. Here are some paragraphs that I admired this month in A Countryman’s Spring Notebook, one of a set of four recent seasonal collections of Bell’s columns. The cadenced phrases of the prose are unemphatically pointed by alliteration and assonance, and surprising and precise images shine out from the fluent wash of countryside evocation (“tabby pattern”, “fluorescent dot”, “five o’clock sun”):

March is a month beautiful for shadows. The sun, glittering now through the keen air, casts shadows of bare boughs on thatched roofs in a tabby pattern. It lays them across harrowed fields, dark upon their lightening brown: where there is young corn, the gleam and stir of the green blades gives the shadows life.

1 March 1958

Now the day which began with a gale and a gallop of old leaves, is dying in a sunset such as Samuel Palmer in his notebook called “raving-mad splendour of orange twilight glow” — yet not more splendid than one spot of fungus I saw on a rotten gatepost this afternoon. That fluorescent dot, that total sky; and a smell of cut grass (yes, I mowed it), and now no wind at all.

12 March 1977

Next a bonfire. Bonfires are in the air on this first day that has really felt like spring. Then, the job done, I can sit watching the river making wriggling snakes of reflected boughs. The mildness makes small birds sing and rooks so pugnacious that they tumble to the ground in a black tangle, disputing over an old nest. The beech buds are pointed, barbing their delicate boughs. An amber cloud lit with five o’clock sun stands behind them. The upper sky is filled with small puffs of sunlight on clouds, though on the horizon behind the willows is that thickening greyness which is the aftermath of a warm day in March. The river pulses with slow bars of light and shadow, perhaps by some contrary urges of light wind and slow tide.

24 March 1956

The final sentence here catches the encounter of water and wind using the rhetorical figure of chiasmas, in which words are repeated in reverse order: “slow bars of light… light wind and slow tide”. And there is a crossword setter’s touch to the way that one kind of “light” becomes another: subtly, as twilight falls, the sun gives way to the cold.

NOTES

Bell’s Countryman Notebooks are published by Slightly Foxed. This extract begins with a story about meeting T.S. Eliot — “as townee a poet as ever lived” — and telling him “why April is the cruellest month to us country people”: https://foxedquarterly.com/adrian-bell-hungry-gap-countrymans-spring-notebook/

The quotations about Adrian Bell’s life as a crossword setter come from Alan Connor, Two Girls, One on Each Knee: The Puzzling, Playful World of the Crossword (2013).

Here are the answers to the Times Crossword No. 1:

Oh my heavens, that first footnote at the end! My jaw dropped. So many things one thinks of as wholly original turn out to have a source of some kind, and each one comes as a shock, somehow. Loved this whole piece, and might read the columns collections now. Have been enjoying Ian Richardson's A Country Diary on Substack, which feels a little related.

Thank you for this post - absolutely fascinating insight.