There’s your new life, blasted with milk

— Ted Berrigan

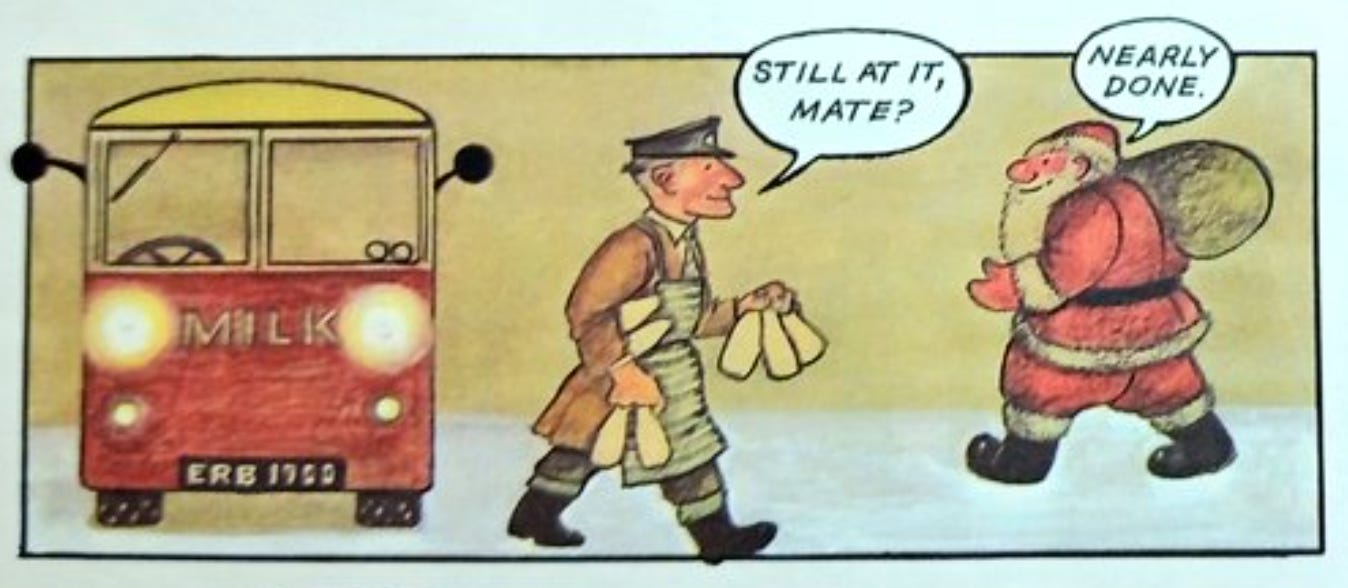

I’ve always felt we lost something with the demise of the glass milk bottle: it’s strange to remember that, half a century ago, every day in Britain began with a recyclable container of perishable liquid being delivered by electric vehicles.

The circular economy of milk bottles was already in decline in America by then, though, as the New-York-born novelist Nicholson Baker lamented in his first book, The Mezzanine (1988):

Home delivery […] managed to hold on for years into the age of the paper carton. It was my first glimpse of the social contract. A man opened our front door and left bottles of milk in the foyer, on credit, removing the previous empties — mutual trust! In second grade we were bussed to a dairy, and saw quart glass bottles in rows rising up out of bins of steaming spray on a machine like a showboat paddle as they were washed.

But paradise is soon lost: the dairy firms merge, the bottles become bigger and plastic. Eventually, the only people paying for milk delivery are “isolated sentimentalists” like Baker’s family, and the whole business ends for good: “I’ll guess and say that it was 1971”.

Around the same time, the New York poet James Schuyler published a prose poem called “Milk” (1969). It begins:

Milk used to come in tall glass, heavy and uncrystalline as frozen melted snow. It rose direct and thick as horse-chestnut tree trunks that do not spread out upon the ground even a little: a shaft of white drink narrowing at the cream and rounded off in a thick-lipped grin. Empty and unrinsed, a diluted milk ghost entrapped and dulled light and vision.

Then things got a little worse: squared, high-shouldered and rounded off in the wrong places, a milk replica of a handmade Danish wooden milk bat. But that was only the beginning. Things got worse than that.

Milk came in waxed paper that swelled and spilled and oozed flat pieces of milk. It had a little lid that didn’t close properly or resisted when pulled so that when it did give way milk jumped out.

Neither of these passages features in Peter Blegvad’s Milk: Through a Glass Darkly, which has just been published by Uniformbooks. But they address directly what the book approaches obliquely: the potent symbolism of milk as a poetic object at the heart of modern society.

Blegvad has been collecting quotations about milk for decades. Curiously, he is also a New Yorker by birth, and began his collection the year Baker gives as the death date of milk delivery: 1971. But his quest was inspired, he says, by reading about Alfred Hitchcock putting a light in a glass of milk for the film Suspicion (1941): “the image seemed portentous, freighted with meaning”.

Now, Blegvad has arranged 342 of his quotations into “a cento or literary collage” to express his feeling that

milk, even without a light in it, and despite the normalising efforts of dairies and marketing boards, is numinous, psychically active

There are plenty of poets in the mix: Anne Carson, Gregory Corso, Francis Ponge, Gertrude Stein, Dylan Thomas, Louis Zukofsky. But the associative method of arrangement — which anonymises its quotations — simultaneously draws poetry out of other texts while adding milk to dairy-free ones. Here is the first page:

Marvellously many materials make milk! Much too many to mention.

You can’t imagine how much milk is in a glass of milk…

… the glass corresponds to the unum vas of alchemy and its contents to the living, semi-organic mixture from which the lapis, endowed with spirit and life, will emerge.

Its cylindricality makes it phallic, while its hollowness makes it uterine.

I put a light in the milk.

You mean a spotlight on it?

No, I put a light right inside the glass because I wanted it to be luminous.

In a hollow rounded space it ended

With a luminous Lamp within suspended…

What does light do specifically to milk? In a matter of minutes it destroys Vitamin A, C and B2, accelerates oxidation of fatty matter, and causes distinctly unpleasant sensations known as “oxide taste” or “fishy taste” or “metallic flavour”.

What about the smell of light?

These quotations are from: Lewis Carroll, Tammy Faye Baker, C.G. Jung, David Sylvester, Alfred Hitchcock, Edward Lear, Daniel Spoerri and John Ashbery. Blegvad himself appears as 271, asking, “Does milk want to express itself through me?”, and answering with a twist on Rimbaud’s “Je est un autre” (“I is an other”): “I is an udder”.

Milk: Through a Glass Darkly is available directly from Uniformbooks, who bring their usual gold-top production values to a rich and unique little anthology: https://www.colinsackett.co.uk/milkthroughaglassdarkly.php?x=73&y=200

This week sees the return of students to universities all over the UK, including the University of East Anglia, where I work. I’ve been teaching literature every September since 2003 and it’s still one of my favourite times of year.

Reading campus fiction, though, is a good way of tempering naive enthusiasm for what the new semester will bring. One classic is Vladimir Nabokov’s Pnin (1957):

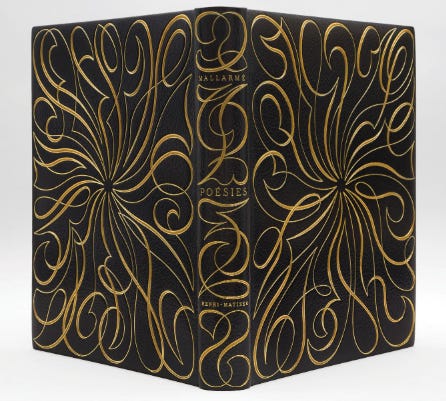

The 1954 Fall Term had begun. Again the marble neck of a homely Venus in the vestibule of Humanities Hall received the vermilion imprint, in applied lipstick, of a mimicked kiss. Again the Waindell Recorder discussed the Parking Problem. Again in the margins of library books earnest freshmen inscribed such helpful glosses as “Description of Nature”, or “Irony”; and in a pretty edition of Mallarme’s poems an especially able scholiast had already underlined in violet ink the difficult word oiseaux and scrawled above it “birds”.

But this year — after months in the limbo of a redundancy “consultation” process, only recently concluded — I have also been reading Srikanth Reddy’s Underworld Lit (Wave Books, 2020), a long episodic prose poem about a humanities professor who tries to teach his students about death:

While outlining the requirements of our first critical essay of the term, I notice a hand rising in world-historical time at the back of the classroom.

“What if I’m ideologically opposed to revision?” asks the red-headed boy in a “New Slaves” t-shirt.

A city bus unloads its pageantry outside the window. A handful of sparrows erupts from the equestrian statue on the quad. I remember Sun Tzu’s advice to humanities instructors, which I review on index cards at the outset of each academic quarter.

Hold out baits to entice the enemy. Feign disorder, and crush him.

The syllabus for the class — “HUM 101. Introduction to the Underworld” — promises:

In this course, students will be ferried across the river of sorrow, subsist on a diet of clay, weigh their hearts against a feather on the infernal balance, and ascend a viewing pagoda in order to gaze upon their homelands until emptied of all emotion […] The goals of the seminar are to introduce students to the posthumous disciplinary regimes of various cultures, and to help them develop the communication skills that are crucial for success in today’s global marketplace.

I’d like to see them teach that in STEM.

My only connection to milk in bottles is that my father worked as a milkman during summers in the 1950s, when he was an undergraduate. (I was born in 1964.)