Pinks #7: Scientifically, Change Will Become Visible

The Incredible Shrinking T.S. Eliot Shortlist / The poetry of Sri Lanka

Welcome to Pinks: free poetry cuttings from Some Flowers Soon

I don’t mean to be all

Come in under the shadow of this red rock

but this week I did feel a little prophetic. Reviewing the shortlist for the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry back in 2017, I said:

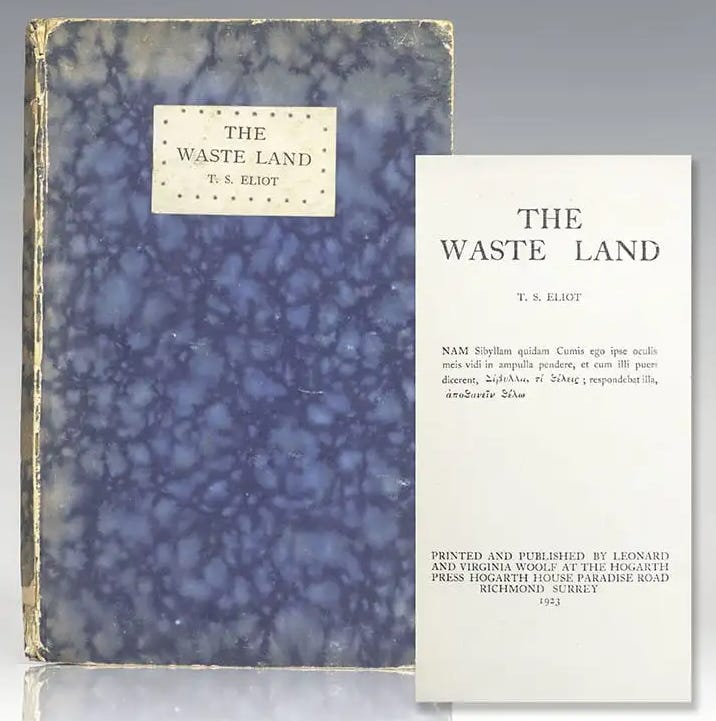

If he were starting out today, T.S. Eliot would not be eligible for the prestigious annual poetry prize that bears his name. The T.S. Eliot Prize is open to any book published in Britain and Ireland. According to the rules of entry, “a ‘book’ shall be defined as having at least 48 pages” — which would disqualify Prufrock and Other Observations, The Waste Land and Ash-Wednesday for starters.

Now, I’m not a voice in the wilderness anymore. This week, the 2023 shortlist of ten poetry books published in Britain and Ireland was announced. The judges noted:

We are aware that two of the titles on the list fall short of the 48 pages required. However, both are fully achieved poetry collections that merit their inclusion on the shortlist.

To which the prize organisers rather awkwardly added:

Katie Farris’s Standing in the Forest of Being Alive and Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin’s The Map of the World were submitted by publishers and put before the judges in error, but when notified of this, the judges declined to exclude them, citing their reason above.

Surely, if nobody bothers with it, it’s time to drop the rule altogether? This might allow a greater variety of work to be considered. As I wrote about the 2017 shortlist:

Eliot’s spectacular originality would also make him a rank outsider for his own trophy. In the last 25 years, the Eliot prize money — now £20,000 — has only gone to a handful of books written with anything like The Waste Land’s experimental daring.

Ironically, however, Eliot may also be to blame for the rule: when the Prize began in 1993, it was run by the Poetry Book Society, an initiative founded in 1953 by… T.S. Eliot, in his role as a poetry editor at Faber and Faber.

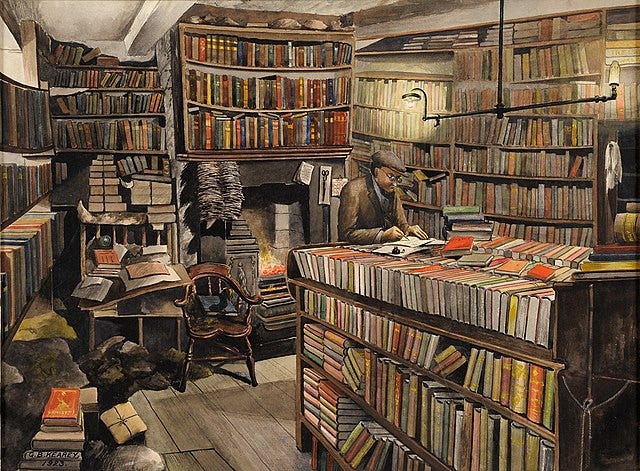

Seventy years ago, buying a new book of poetry required more effort on the part of the customer than clicking a couple of links. By selecting and sending four books a year to their members, the Poetry Book Society hoped that it would be

of special benefit to those who live in isolated parts of the country, or overseas, and find it difficult to be in touch with a good bookseller

The 48-page definition of a “book” has a bit more justification in this historical context: booksellers, and publishers, wanted a spine big enough to stand out on shop shelves.

For years, the four annual Poetry Book Society selections were given an automatic place on the Eliot Prize shortlist. But times change: it’s no longer necessary to know a good bookseller to buy a good poetry book; the PBS no longer runs the Eliot Prize; and books of poems come in all shapes and sizes, from all sorts of presses.

So it’s good news that the bending of the rule has allowed two smaller poetry imprints — Pavilion Poetry and The Gallery Press — onto the shortlist. What’s odd, though, is that both books are currently listed on their publishers’ websites as having, respectively, 58 pages (Standing in the Forest of Being Alive) and 64 pages (The Map of the World). Did the proofs shrink at the printers?

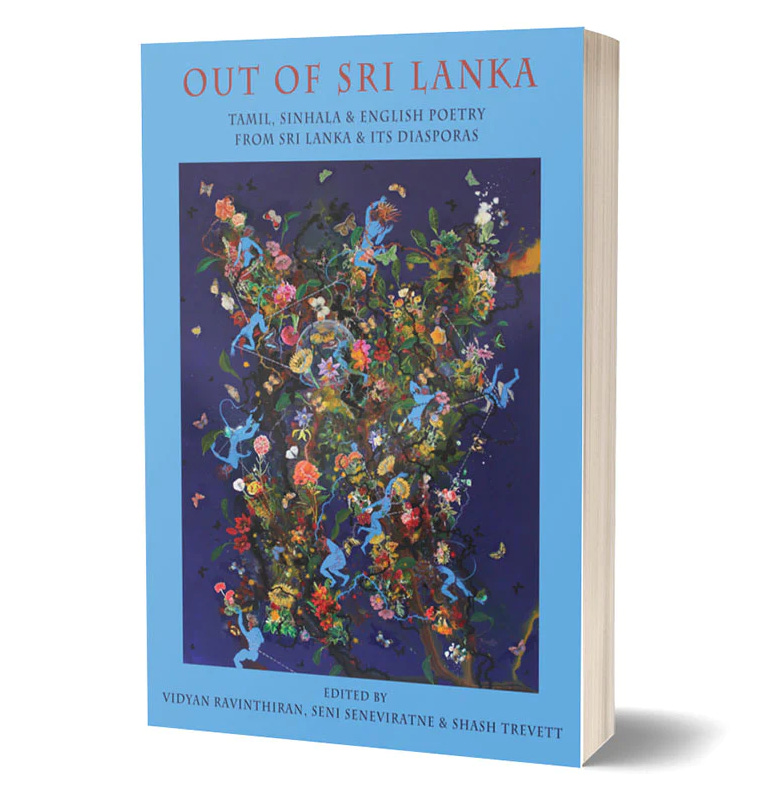

There are too many books one might pick up to mark National Poetry Day this year, with its theme of Refuge. My recommendation is one of the most important anthologies to have appeared recently: Out of Sri Lanka: Tamil, Sinhala and English Poetry from Sri Lanka and its Diasporas (Bloodaxe, 2023). It’s a huge achievement by its three editors — Vidyan Ravinthiran, Seni Seneviratne and Shash Trevett — who have placed 400 pages of poetry into an enormous gap in Anglophone literary culture.

As they write in their introduction:

In terms of media, literary and political representation, Sri Lankan and disaporic people are more than minoritised: they are hyperminoritised. They are neglected by diversity initiatives, they have no commemorative events dedicated to their histories, their inheritances (both traumatic and cultural) are simply not talked about or understood.

The result is what they call a “peculiar sense of isolation” — something that emerges acutely in the many poems written in the book out of an experience of exile. One haunting instance is “Fire” by Sharmila Seyyid, a Tamil writer forced into exile due to her activism for women’s rights in Sri Lanka. The translation is by Pramila Venkateswaran:

The day before yesterdaywhen I ran toward the streetsome chased the fire that boundedlike a peeled papaya.This illusory fire cannot be cradled in your hands,nor does it abide in your focus.It does not have the habit of impinging on youit does not burnit does not adhere.The fire escapes its pursuers somehow,enters through the back door into the houseto stay.I am sleeping in a fire-lit room,embers I secretly keep hidden in my bag.Three times a day,half an hour ahead or behind my meal time,I eat a handful of embers.In the coming days,scientifically, change will become visible.

That single word, “scientifically”, suddenly sharpens the irony and poignancy of the fable, as the image of fire like a “peeled papaya” shrinks to embers that are hoarded like the self-medication of vitamin supplements.

I was also moved by the poem chosen to represent (Meary James Thurairajah) Tambimuttu, whose name I knew mainly from his association with Eliot (he was said to be able to recite “yards of The Waste Land”). Coming to England in 1938 at the age of 22, Tambimuttu almost immediately founded the magazine Poetry London, and in the Forties published books by writers such as Keith Douglas, Vladimir Nabokov and Elizabeth Smart.

His poem, “My Country, My Village”, begins with happy, playfully rhymed memories of childhood —

I was four or five, and grandfather, the poet,

In turban of gold and coat of black was a prince

Who was kind to us; he flicked the coiled whip,

And off we went down limestone white roads

Fringed with lantana eyes; from prints

He cut us paper dolls, with a clever snip.

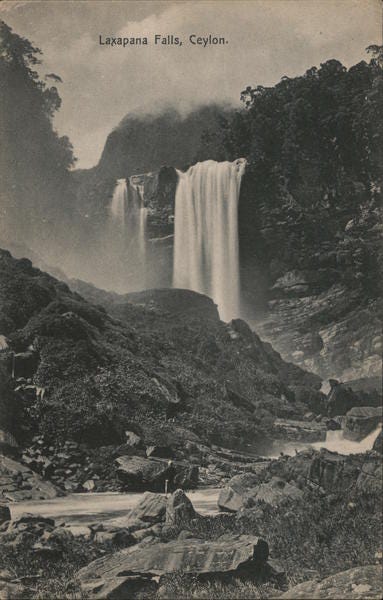

and ends by evoking the island of Ceylon as the woman of the Sri Lankan national anthem, originally titled “Namo Namo Matha” (“Glory to thy name, O Mother”):

Her eye a blackbird among tumbling bushes,

Her lashes, the black silk of a deep night,

Her body the pure long scarf of Laxapana,

Lights of an ocean liner in her tresses,

Black tresses, filled with dark and light;

Cry, O cry, Namo, Namo Matha.

NOTES

More coverage of the Out of Sri Lanka anthology, including reviews and interviews, can be found here:

https://www.bloodaxebooks.com/news?articleid=1310

Although the Poetry Book Society is no longer involved in the T.S. Eliot Prize, it continues to be a good place to find out about and buy new poetry books (including those under 48 pages):

https://www.poetrybooks.co.uk/

Famously, Eliot added his Notes to The Waste Land to bulk out the first American edition, resulting in 64 generously-spaced pages. But the first British edition in 1923 — printed and published by Leonard and Virginia Woolf — was a modest 35, including blanks.

You can read more fun facts about Eliot here:

Practical Chat

It’s now one hundred years since T.S. Eliot published The Waste Land, and there will be no end of talk about it, especially in April. So we’re all going need some better ice-breakers than ‘did you know his name is an anagram of TOILETS’. Here, culled from years of research, are a handful of little-known Eliot facts to throw into any centenary conversatio…