‘I / fucking love you sonnets’ (Jeff Hilson). I couldn’t have put it better myself. And I’ve realised recently that what I really love is lots of sonnets.

It’s the start of the university term, and for the last two weeks I’ve been talking with my first-year students about Terrance Hayes’ American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin (2018). Written every day after the election of Donald Trump, Hayes responded to the victory for white supremacy it represented with driven, mercurial energy. Every time I pick the book up, the pages seem to start moving with living rhythms, like videos on auto-play. It’s a work of unfakeable inspiration.

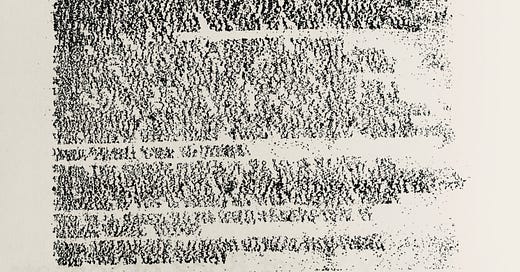

The way that Hayes has said he wrote American Sonnets — using the same poem title, so as not to know what the next day would bring — also makes me wonder if one of the deepest appeals of the sonnet is its dailyness. Is there something about fourteen lines that reminds us of the rise and fall of the sun, with the volta intervening between the eight-hour working day and the six free lines of evening? (Am I wondering this because autumn begins in the UK as we fall below fourteen hours of daylight?) For pure visual punning, you can’t beat Bob Cobbing’s sunset-sonnet ‘Sunnet’:

Among the sonnets I have enjoyed this year are those spread through Ken Babstock’s Swivelmount (Coach House Books, 2020), including the beautifully gloomy allegory ‘Wetterhaus’, where the tension between the male and female figures in an old-fashioned weather house holds across the volta (‘blue breaking through grey. Another thin day’). And perhaps it is the volta, the turning moment of the mind, when the sonnet’s day becomes a diary entry, that makes it such an addictively all-purpose form.

That’s what I’ve been thinking as I read Hannah Lowe’s third collection, The Kids (Bloodaxe, 2021), which looks back on the decade she spent as a teacher at an inner London sixth-form college. Like Mimi Khalvati, to whom the final poem of the book is dedicated, Lowe writes what might be called realist sonnets, where a muted but ranging rhyme scheme generates the random details of a telling story.

The sestet of ‘Balloons’ runs:

But the kids I taught, who came to me at the edge

of childhood — was it really then too late?

In the common room we said it only took

one class, one hour, to know the grades they’d get,

as though there were a Magic 8 ball, wedged

at one conclusion, no matter how hard you shook.

The Magic 8 ball is a wonderfully solid trouvaille, an image found between ‘edge’ and ‘wedged’, which transforms the children’s balloons of the octave into a different kind of eight: a cheap fortune-telling toy that answers, ‘Don’t count on it’.

Lowe’s sonnets achieve their lucid acuteness through these twists, as the volta’s ‘loud // clack-snap of steel’ (‘Sonnet for the Punched Pocket’) starts a turn against the inevitability of injury and injustice: a hard shake of the fixed scheme.