Of all the things I might have posted about to generate correspondence, I didn’t expect it to be mugwort. But here we are: after last week’s wander through a wildflower guide — in which I doubted the claim that mugwort “has often been written about by poets” — I learnt some interesting things from readers who got in touch.

First was

, who pointed out that the traditional verse quoted in the guide on mugwort’s healing properties also appeared in Sylvia Townsend Warner’s novel Lolly Willowes (1926):Nannie Quantrell placed much trust in the property of young nettles eaten as spring greens to clear the blood, quoting emphatically and rhythmically a rhyme her grandmother had taught her:

If they would eat nettles in March

And drink mugwort in May,

So many fine young maidens

Would not go to the clay.Laura would very willingly have drunk mugwort in May too, for this rhyme of Nannie’s, so often and so impressively rehearsed, had taken fast hold of her imagination.

We both wondered if Warner had actually invented this rhyme — but I’ve subsequently discovered that it appears in Michael Denham’s A collection of proverbs and popular sayings relating to the seasons, the weather, and agricultural pursuits (1859) as “a piece of Scottish superstition”. You can more learn more about Lolly Willowes here:

Then there was Billy Mills (on Substack as

) who reported the “delightful discovery […] that the Irish name for mugwort is ‘Mongach meisce’, which translates as ‘drunken monk’” — possibly because it was used in brewing. Billy also suggested another poem on the powers of mugwort: the Old English “Nine Herbs Charm”, as translated by the poet and scholar Bill Griffiths, which begins:Recall, mugwort, what you declared,

what you established, at the Great Council.

”Unique” you are called, most senior of herbs.

You prevail against 3 and against 30

you prevail against poison and against infection,

you prevail against the harmful one that throughout the land travels.

As Griffiths comments, “this long verse charm is one of the most enigmatic of Old English texts”. The “Great Council” is baffling, but Griffiths’ footnote to the last line suggests the “harmful one” may be an epidemic, “perhaps the yellow plague [of 664], personified in Welsh sources as ‘a most strange creature from the sea marsh… his hair, his teeth, and his eyes being as gold.’”

Lastly, I heard from Ian Heames, who took up the challenge of my idle comment

I suspect you might be able to find [mugwort] mentioned somewhere in the prolific recent work of J.H. Prynne, which is absolutely abuzz with wildflower names. But I’m not combing through two dozen pamphlets to confirm this.

to report:

No mugwort it seems, but thirty-seven instances (by my count) of fourteen different worts, six of which are unique, and others that spring up all over the place.

As the publisher of many of Prynne’s recent pamphlets through Face Press, Ian is well placed to crunch these numbers. Stitchwort, it seems, is the most mentioned of all, and the pamphlet with the most worts in total (7) is At Raucous Purposeful (Broken Sleep, 2022) — whose stitchwort line I quoted in my piece on late Prynne for the Times Literary Supplement in 2023 (“Such watch nuthatch, acrobatic darting head-down fawn stitchwort. / Patchwork”.) So for paid subscribers this week, here is that piece in full.

Timelike delirium

cools at this crossing, with your head

in my arms. The ship steadies

and the bird also; from frenzy

to darker fields we go.

These lines, from the end of of J. H. Prynne’s “diurnal” sequence Into the Day (1972), have been much admired. The American poet George Oppen — an austere judge, his tastes formed on high modernism — wrote to its author: “Can scarcely credit the existence of the last poem [...] its incredible beauty.” Douglas Oliver, Prynne’s friend and contemporary, told him: “the sequence is patient and [...] that patience is beautiful”. Beautiful, but also true: “the most considerable thing I can say about the last poem is quite simply that it is correct”.

Being correct has been a passion for Prynne. Appointed a fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge in 1962, he spent his career teaching English and feeding his polymathic imagination with late nights in the library. An early correspondent was Charles Olson — another modernist of Oppen’s generation — to whom he sent long, arcane bibliographies. “Prynne is so — he’s knowing”, Olson marvelled, “knowing like mad.”

Prynne’s overwhelmingly generous erudition defines the dynamic of his correspondence with Oliver, which begins in 1967 with the latter tentatively introducing himself as a journalist from the Cambridge Evening News and enclosing poems for “frank criticism”. The next two letters, both from Prynne, comprise photocopies of Renaissance anatomical drawings and a reading list on body perception: “probably unuseful”, he comments, “you might shred it in your soup”.

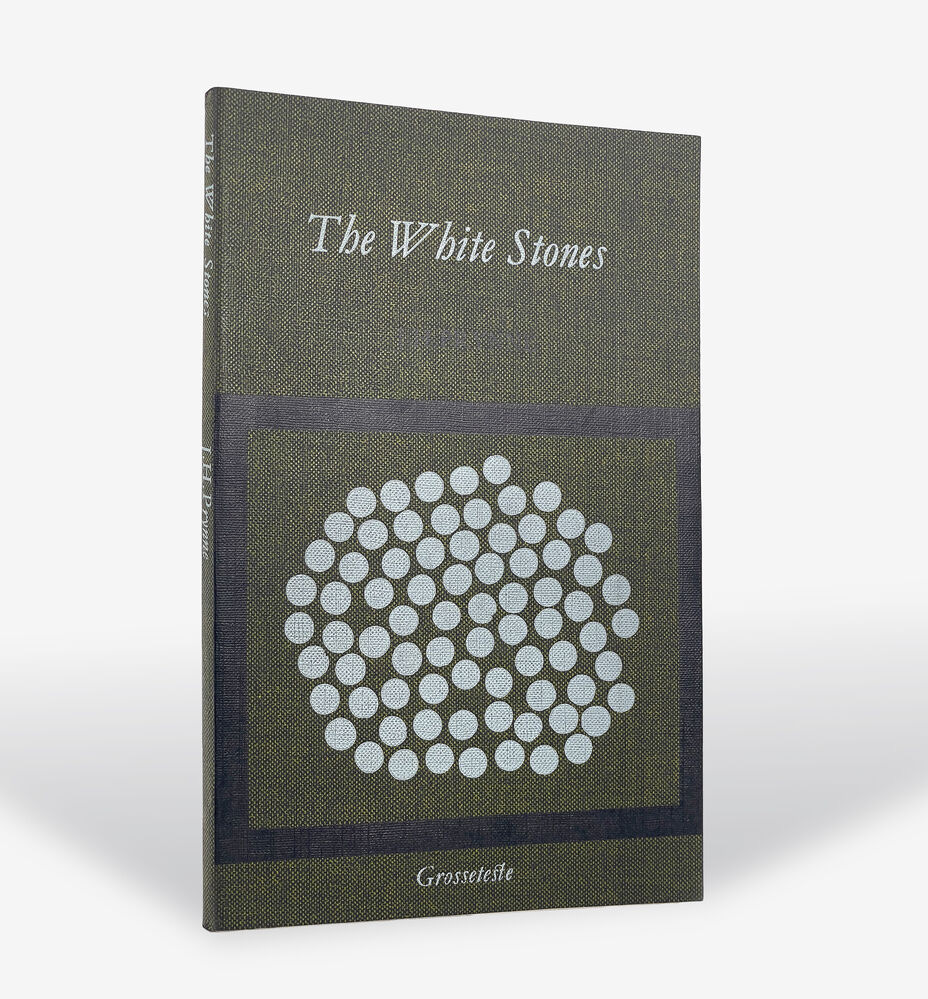

Thus, as Prynne began to make his reputation with his early masterpiece The White Stones (1969), Oliver was welcomed into his inner circle and its tone of high inquiry salted with jocularity. (Not coincidentally, the Cambridge of this time also produced Monty Python’s song about boozy philosophers). To anyone who has admired the Romantically ambitious verse that resulted, the recent volume of letters edited by Joe Luna — and produced to the usual fine standards of its publisher, The Last Books — could hardly be more absorbing and valuable.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.