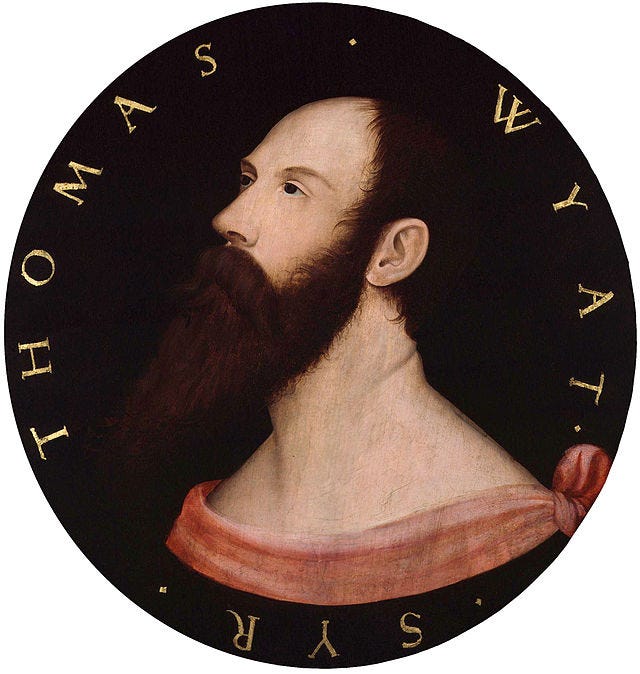

“When Wyatt writes, his lines fledge feathers, and unfolding this plumage they dive below their meaning and skim above it […] You are deceived if you think you grasp his meaning. You close your eyes as it flies away.”

Hilary Mantel, Bring Up the Bodies

We are used to talking about imagery in poems, rarely how that imagery is lit. Yet lack of light is what is metaphorically implied when we speak of poetry as “obscure”. We use the metaphor as a way of expressing the unclear meaning of words. What, though, if we also thought about the darkness of poems literally, as a fact of time and place?

I began to think about historical darkness on Sunday night, as I watched the opening episode of the BBC adaptation of The Mirror and the Light, the last of Hilary Mantel’s novels on the rise and fall of Thomas Cromwell at the court of Henry VIII. It’s finely acted, scripted and directed. But what I found fascinating on the screen over the course of an hour were the contrasts of light and dark, as the camera moved from the glitter of royal ceremony to candlelit diplomacy to the shades of Cromwell’s midnight study. Whether things were to be done by day or night must have been a constant consideration in such a world, where walls were thick and windows a luxury.

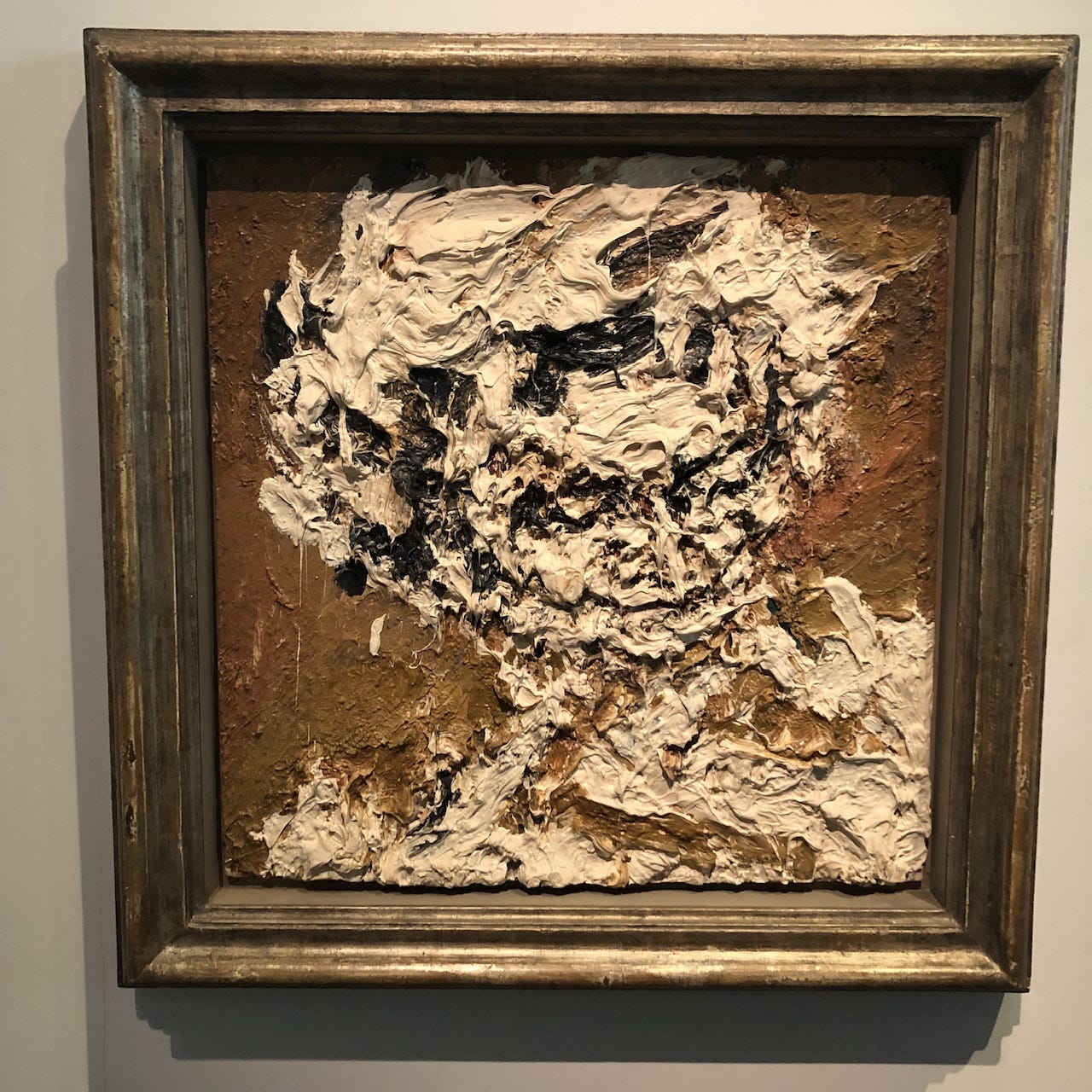

Then, on Monday, the great painter Frank Auerbach died. Two of his portraits are in the permanent collection of the Sainsbury Centre at the University of East Anglia, a few minutes walk from where I work. Being able to stand in front of one of these masterpieces on my lunchbreak, with their amazingly living light and shade — one in charcoal, one in oils — is a luxury that still seems a little unreal.

Looking this week at “Head of Gerda Boehm” (1956), with its thick, creamy oils that seem almost to run away on the wind, I remembered Auerbach’s fondness for what Robert Frost said about poetry:

Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting

A painting, Auerbach said, should be

a shape riding on its own melting into light and space; it never stops moving backwards and forwards

Auerbach made this remark to the art historian Catherine Lampert. He also quoted Frost in an interview for the arts documentary series The South Bank Show in 1978, where he followed it with another quotation — from Sir Thomas Wyatt:

Robert Frost said that a poem was like ice on a stove — it rode on its own melting. And I take that to be that there are these firm words on the page, as it might be,

They flee from me that sometime did me seek

stepping with naked foot within my chamber.

A few words, absolutely stark and clear on the page, and the reverberations and inner melodies and the possibilities of interaction are so great, that these few black shapes on a white sheet of paper can lead to a whole world of complex, subtle sensation.

Auerbach’s slight misquotation of the second line (“With naked foot stalking in my chamber”) can be forgiven for the subtlety of his response, which reflects on the visual alchemy whereby print is silently transformed into sound and feeling. Thinking about it again this week, with the weak light and heavy shade of the Tudor court in my mind’s eye, I felt perhaps that I saw why these lines should resonate so much with a painter. From “black shapes on a white sheet of paper” the startling negative of a “naked foot” emerges: a white shape moving through the black space of a chamber.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.