The Blue and the Dim and the Dark Cloths

Why the secret ingredient of W.B. Yeats' most memorised poem is rhythm

The speech of the people […] delighted in rhythmical animation

W.B. Yeats, What is “Popular Poetry”?

I was talking recently with someone who said they didn’t know much about poetry, but that Yeats’ “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven” (1899) had stayed with them since they copied it out on a piece of card as a teenager. I also wrote its eight lines out and memorised them at that age. “Tread softly because you tread on my dreams”, we said, together, pleased to have the last line by heart still.

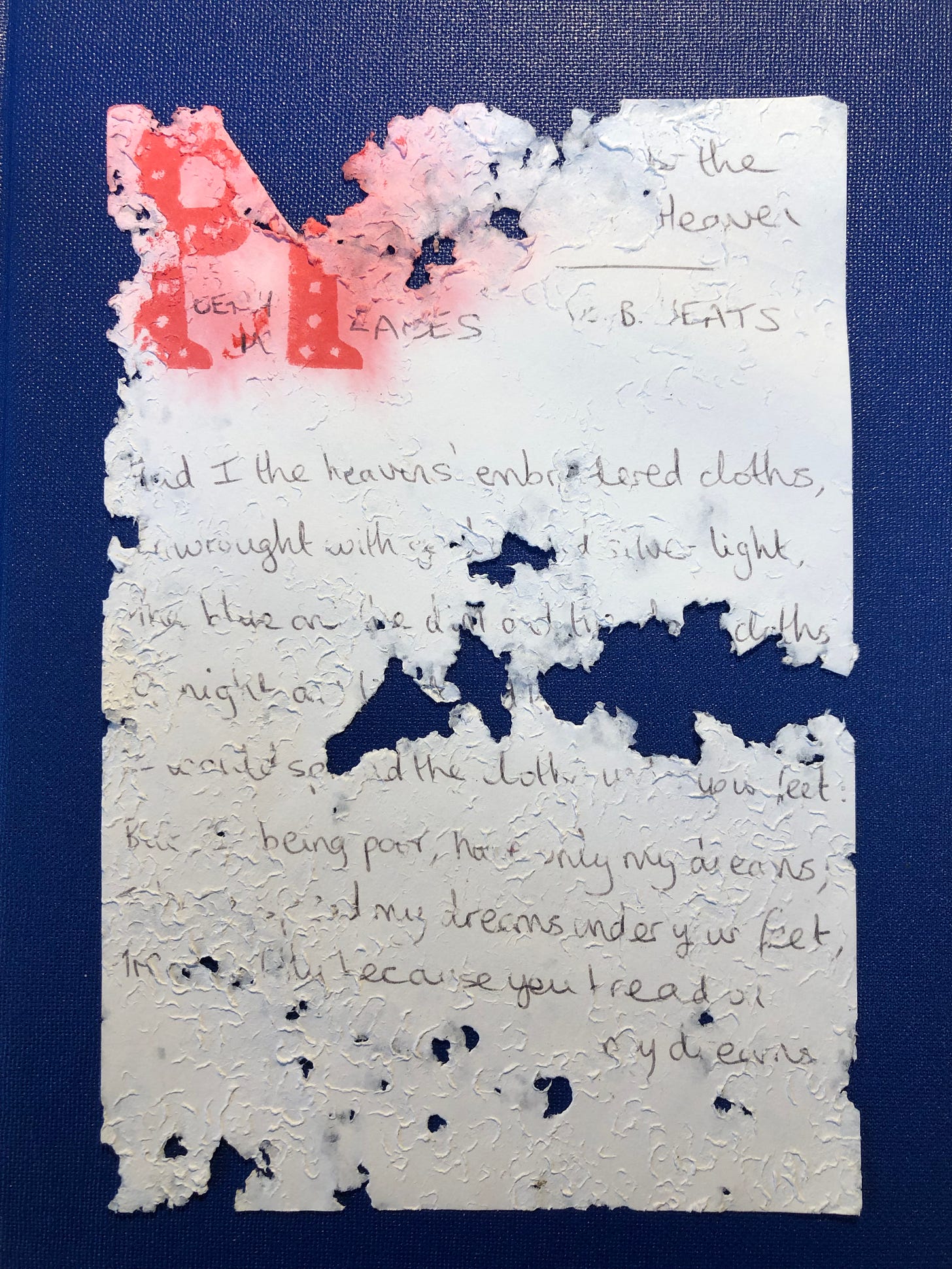

It reminded me that I once found a brittle, weather-bitten, handwritten copy of the poem in the street, which I have used as a bookmark in my copy of Yeats’ poems ever since. It also reminded me that, a couple of years ago, I asked people on Twitter if there was a poem they could recite from memory without hesitation. I got a lot of replies, and there were two clear winners: “Jabberwocky” by Lewis Carroll and “This Be the Verse” by Philip Larkin (“They fuck you up, your mum and dad”). But third among the nominations was “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven”.

It’s fairly obvious why the poems by Carroll and Larkin should be popular to recite. They are both party pieces, intended to make people laugh: one with its made-up words and one with its rude one. They also have a similarly memorable form: rhyming quatrains of regular four-stress lines (iambic tetrameter), which Carroll varies with the ballad measure of an internally rhyming third line (“O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!”) and a final three-stress line (“He chortled in his joy”).

The Yeats poem has none of this except the four-stress line. In fact, its form may be unique: an eight-line stanza which instead of a rhyme scheme repeats the same words ababcdcd. Here it is:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Why does this appeal to memorisation like the Larkin and the Carroll? I think the common mnemonic ingredient of all three poems is symmetry. In the case of “Jabberwocky”, the poem begins and ends with the same nonsense quatrain (“‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves”), enclosing a concentric narrative of two stanzas of speech around three of action. “This Be the Verse” declares its shock truth with tongue-in-cheek neatness over three stanzas, each of which begins with a restatement of the same idea of inherited unhappiness (“They fuck you up, your mum and dad” / “For they were fucked up in their turn” / “Man hands on misery to man”). In the Yeats, meanwhile, the formal conceit of symmetry is most pronounced of all, overriding rhyme with almost-pure repetition: “I would spread the cloths under your feet” / “I have spread my dreams under your feet”.

Yet, remarkably, in an eight-line poem built on repetition, only the two lines I’ve just quoted have exactly the same rhythm — and this, I think, is what makes it so addictively recitable. Getting to the end of “He Wishes for the Cloths of Heaven” is like solving one of those sliding tile puzzles, as all the little pieces click into place.

The following discussion will be a bit technical, but I will try to explain everything as we go. What I want to show is how subtle metrical variation — for which Yeats had a genius — can appeal to readers who have no interest in analysing it. You memorise a poem because it moves you, not because of how it deploys the anapaest (da da DUM) among iambs (da DUM). And yet all this is part of how it moves you.

We can see Yeats fine-tuning the phrasing of his lines in a notebook draft of the poem. Lines 1, 2 and 4 seem to come quickly. But for the third line, he has

The grey & golden & purple cloths

which then gets crossed-out and toned down to

The dim & the blue and the grey cloths

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.