This week, in honour of Peter Gizzi winning the T.S. Eliot Prize for Poetry 2024 for his collection Fierce Elegy (Penguin), I have revised a reading of a poem from an earlier book, Threshold Songs (2011), which thinks, imaginatively and memorably, about Eliot’s idea of “tradition”. It’s from the same long essay about Gizzi’s love of British modernist poetry (and particularly, W.S. Graham) that I also revisited here:

The poem is a bit too long to reprint in full, but you should be able to read it here or, with JSTOR access, here. For ease, I’ll put these links at the end of the post too.

The title of Peter Gizzi’s poem “Tradition & the Indivisible Talent” announces its intention to engage with T.S. Eliot, the American who became an English poet. But it does so via Jack Spicer, whose lectures Gizzi edited and published as The House That Jack Built (1998). In his afterword, “Jack Spicer and the Practice of Reading,” Gizzi offers a definition of the concept of “tradition” in Spicer’s work:

His poems create a space that both the living and the dead share in the act of reading. […] Hence the poem is always in the present; its time is outside time. The poem is not immortal because it endures through the ages but because it exists in all ages at once. For Spicer this constitutes “tradition”.

Gizzi’s phrasing here (“the living and the dead”) echoes Eliot’s famous vision of a transcendent canon in his 1919 essay “Tradition and the Individual Talent”, which ends by warning that that the poet must be conscious “not of what is dead, but of what is already living”. But there is implicit disagreement, too, with the way that, for Eliot, the present is “directed by” the past — an idea that Spicer resisted. Asked about his notion of “the Outside” as a mysterious force that dictates poetry to poets, and whether this has “anything to do with former poets”, Spicer replied, equivocally:

I think in some senses it can [...] I think it’s more a tradition of the past [...] I think when you pay attention to tradition like Eliot does, you get into all sorts of the most soupy static that you can possibly have, so that you don’t know what is your reading of English literature and what is ghosts.

Spicer’s notion of “soupy static” alludes to his belief that “the poet is a radio,” receiving all sorts of signals from the Outside. By concentrating too consciously on canonical poets, Spicer suggests, Eliot is in danger of tuning out other voices.

The inclusive spirit of this argument informs Gizzi’s diction of “Tradition & the Indivisible Talent,” which is sprinkled with American vernacular quirks. The first stanza introduces the poem’s voice as a kind of comic bickering about wisdom:

If all the world says something

we think then we know something

don’t we? And then the blank screen

or memory again. You crazy.

No, you crazy.

The Romantic lyric “I” that haunts so much of Gizzi’s writing recovers its poise sufficiently to then make an elegant statement about its own organic and inspired nature:

I am rooted but alive.

I am flowering and dying.

I am you the wind says, the wind.

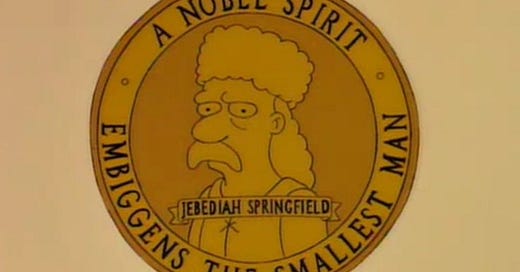

But the next stanza wobbles off into the diction of comedy again: “The embiggened afternoon / was just getting started.” “Embiggen” is a neologism from The Simpsons, which sends up the pomp of the American dream as embodied by the small town of Springfield. The motto of Springfield is “A noble spirit embiggens the smallest man,” and the “Springfield Song” includes the lines “That a people might embiggen America, / That a man might embiggen his soul.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.