At the end of a very hot day two weeks ago, I stood in a cafe in Norwich, the city where I live, to give a talk about poetry. The occasion was a new book I’ve just edited: Ron Nevett’s Norwich Sonnets and Other Poems. Ron, who began his career in the Poetry Corner of the Norwich Evening News, shares Wallace Stevens’ view that

I am not a troubadour and I think the public reading of poetry is particularly ghastly

— which is a shame, because his poems, and their sometimes surprising rhymes, sound best in his own Norfolk accent (as you can hear from the recording below). Instead, I offered to speak about Ron’s poems in relation to some research I’ve done that promises to have far-reaching consequences for English Literature as we know it.

Several of the Norwich Sonnets previously appeared in an anthology of Norfolk poetry that I wrote about here:

Now, the full sequence has been published by Waterland Books, alongside other poems on Norwich themes (Ron writes of nothing else). In my talk, I proposed “the Norwich sonnet” as a term with a history that could unseat the “upstart crow” Shakespeare from his dominance of the form. Here is part of what I said that evening.

First of all, I’d like to thank everyone for coming out on this very warm evening for the sake of poetry. W.H. Auden said “Poetry makes nothing happen”, and I’m afraid it’s not about to cool us down. But I want you to imagine instead that you are warm because you are sitting very close to the fire on Christmas Eve in King’s College, Cambridge. The provost of the college, Montague Rhodes James, better known as M.R. James, is about to read you his latest ghost story, which will, characteristically, begin as the confession of an obsessive scholar who has stumbled upon something inexplicable in the wilds of East Anglia. Here are the opening paragraphs:

During the summer of 1960 I was in England searching for evidence of the authorship of a manuscript in the Folger Library, The Famous History of St George, by G.B. I believed G.B. to be Gawdy Brampton of Blo Norton, Norfolk. My case needed the proof that only a signature or other holograph might provide. A suggestion in the work of Francis Blomefield, the eighteenth-century antiquarian, led me to try the Norfolk Record Office in Norwich. As I stepped off the bus in Norwich, a sudden shower sent me into the nearest doorway, that of Norwich Public Library. After a few minutes I recalled that Francis Blomefield’s commonplace book was kept in this library.

Receiving the book from the librarian, I learned that Blomefield had had this miscellany bound in 1726. Much of the material was in the collector’s hand, but some had been contributed by others. There were epitaphs, descriptions of churches, wills, and notes on Norfolk families. There was also “A little book written by Gaudie Brampton” in handwriting which was identical with that of the photostat of the Folger manuscript I had brought along for comparison. The autobiographical poetry in “A little Booke” provided solutions to all of the problems which had seemed insoluble.

Afterwards I glanced briefly through the remaining manuscripts bound in the back of the commonplace book. One looked vaguely familiar, but I passed over it to examine law lectures, a legal case, and a short necrology which completed the collection, resolving to study all of the materials more closely on my next visit to Norwich. I did not return that summer.

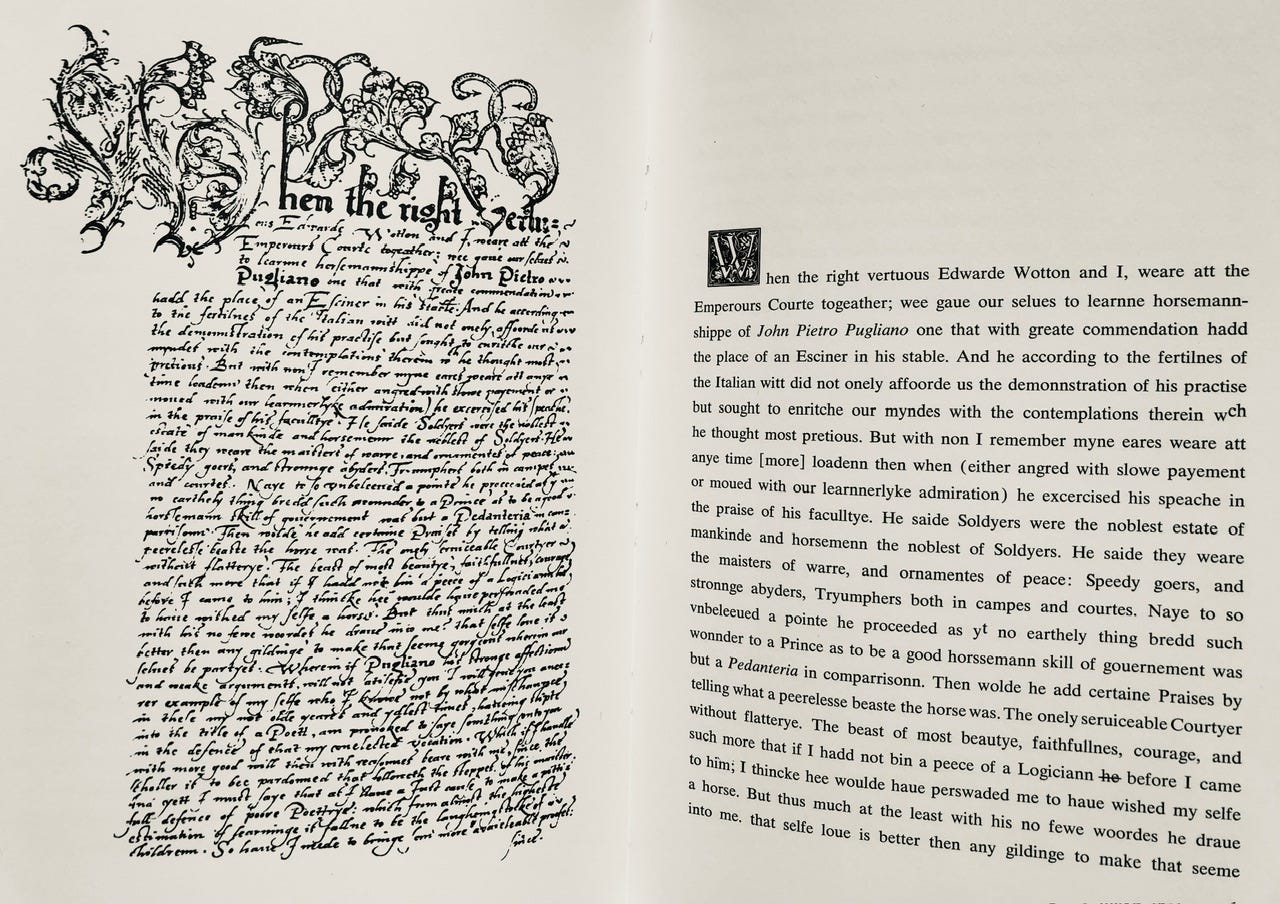

One night in March, 1966, I suddenly recalled the commonplace book. Wondering what I had seen in it that had seemed so familiar, I wrote to the City Librarian of Norwich requesting a microfilm of the entire volume. The book had been transferred to the Record Office, but in time I was provided with the films. The first line of the manuscript immediately following the Brampton poetry was “When the right vertuous Edwarde Wotton and I weare att the Emperours Courte together…” Of course this had been familiar back there in 1960: it was Sir Philip Sidney’s Apology for Poetry.

I hope these strange paragraphs may have sent a cooling chill down your spine. They are not in fact from an M.R. James ghost story, but the introduction to a facsimile edition of what is now known as the Norwich Sidney Manuscript, which contains The Apology for Poetry by Sir Philip Sidney. The scholar I have been quoting is Mary R. Mahl, who established that her discovery was the earliest text of Sidney’s Apology yet discovered, “no more than one step removed from Sidney’s holograph” — a scribe’s copy, that is, of the lost original. It had disappeared from view for years in Norwich Library because the badly water-stained manuscript had been confusingly listed in the commonplace book as “A treatise of Horsmann Shipp” — presumably because Sidney’s long, learned essay on poetry opens with a paragraph describing how he and Edward Wooton were instructed in the ways of horsemanship by a teacher so passionate that “I think he would have persuaded me to have wished myself a horse”.

These, however, are only Sidney’s opening remarks, made to illustrate the proposition that the best way to advocate for something is to speak passionately from experience — and he goes on to propose that “having slipped into the title of a poet” he will “say something unto you in the defense of that my unelected vocation”. I won’t summarise the rest of Sidney’s apology, but I will give you an abbreviated version of the conclusion:

But if—fie of such a but!— […] you cannot hear the planet-like music of poetry; if you have so earth-creeping a mind that it cannot lift itself up to look to the sky of poetry […] yet thus much curse I must send you in the behalf of all poets:—that while you live, you live in love, and never get favour for lacking skill of a sonnet; and when you die, your memory die from the earth for want of an epitaph.

Here, in a rousing rhetorical period, Sidney gives us two of the ways that poetry might have an enduring and important place in our lives. The first is the idea that it may move us to love — a love sonnet may find favour with a lover — and the second is that it may move us to remember, in the form of a finely turned epitaph.

It feels appropriate to me that the earliest known manuscript of Sidney’s argument should have survived in Norwich. Because the argument that I want to make this evening is that Norwich is, in fact, the spiritual home of the English sonnet, as the enduring poetic form of both love and memory.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.