Earlier this year, I shared an extract from my book-in-progress on the prose poem in Britain and Ireland:

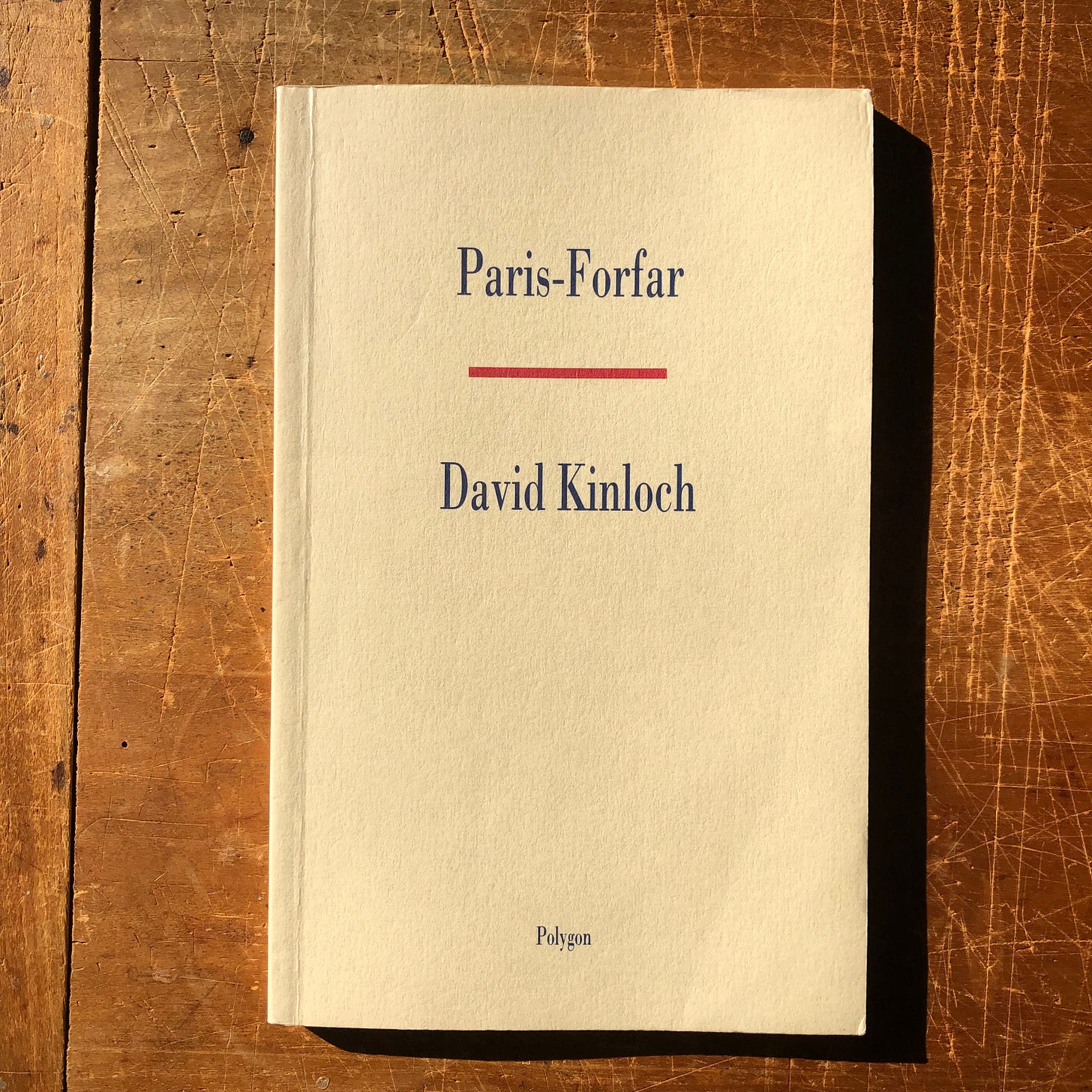

As far as I’m aware, only two previous histories of this subject have been published, and one of them is in German — which tells you something about how it has been neglected by literary critics here. Neither of those histories, however, covers the last fifty years, so there’s also a lot of new writing to consider. One book that I’ve come to admire more and more as I write about the prose poem in the Nineties is David Kinloch’s debut collection, Paris-Forfar (1994), which thirty years later looks like an early landmark for the kind of formally experimental cartography of identity that characterises much British poetry now. To quote the cover of the first edition:

Mixing Scots and English, verse lyrics with prose poems, David Kinloch’s poetry explores with brio areas of sexual and linguistic marginality, suggesting the strange and haunting links between them.

To write, as Kinloch did, about being gay in the Eighties — and about the AIDS crisis — was to write in and about an atmosphere of fear and hostility. The coming-out scene of Andrew Scott’s character in Andrew Haigh’s film All of Us Strangers (2023) captures this well in the frozen anxiety of his mother, played by Claire Foy. And that adjective, “frozen”, lies behind the whole of the poem below.

Paris-Forfar is out of print, and quite rare second-hand. It would be great to see it republished to take its place on the shelves alongside other classic collections from the Nineties that remain available. In the meantime, a selection can be found in Kinloch’s Greengown: New and Selected Poems (2022): https://www.carcanet.co.uk/cgi-bin/indexer?product=9781800172791. I’m grateful to Carcanet Press for permission to reprint the title poem in full here; my discussion of it follows.

PARIS-FORFAR

From the window of the Hardie-Condie Café, I see the ghost of a rich friend of my grandmother drive down Forfar’s Main Street in a Rolls-Royce I was sick in as a child. Behind me the watercolours of stick girls walking through trees are misted blobs percolating in coffee steam. Mother comes in like Scott of the Antarctic carrying tents of shopping. The garçon brings a cappuccino and croissants on which she wields her knife with the off-frantic precision of violins in Hitchcock’s shower scene. Soon I will tell her. Show her dust in the sugar spoon. Her knife gouges craters in the dough like an ice-axe and she tells the story of nineteen Siberian ponies she queued behind in the supermarket. Of Captain Oates who boxed her fallen “Ariel”. The chocolate from the cappuccino has gone all over her saucer. There is a scene and silence. Now tell her. Tell her above the coffee table which scrapes with the masked voice of a pier seeming to let in some waters, returning others to the sea, diverting the pack-ice which skirts around its legs. Tell her a fact about you she knows but does not know and which you will tell her except that the surviving ponies are killed and the food depot named Desolation Camp made from their carcasses keeps getting in the way. From this table we will write postcards, make wireless contact with home and I will tell her of King Edward VII Land, of how I have been with Dr Wilson and then alone, so alone, in day-blizzards just eleven miles short of the Pole and ask her to follow me. I am afraid she has been there already. She smiles like the Great Beardmore Glacier and goes out into the street with stick girls to the thirty-four sledgedogs and the motor-sledges. You are too late. Amundsen is in Forfar. She has an appointment. Behind me I can sense the canvases, the dried grasses pressed into their grain like eczema on an open palm. Later I will discover her diary and what I told her.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.