When literary critics talk about “echoes” of other writers in a poem, it can seem a dull business — as though the poet were writing with books propped open on the desk. But echoes in general are the life of poetry: the repeated sounds that give it depth and resonance as a thought process that happens in the ear. And in the best poems these two kinds of echo — the external and the internal — are blended: the borrowings become part of the sound world of the new poem.

W.H. Auden seems to have gone through life hearing potential poetry everywhere. The columnist Miles Kington once remembered him giving a lecture in which he said:

We must not make the mistake of thinking that poetry is only found in the work of poets. You can find it everywhere where words are creatively used. You can find it in a lot of advertising. Never underestimate advertisers. One of the most impressive lines of poetry I have ever come across was contained in an ad for a deodorant. This was the line, “It’s always August underneath your arms...”

Auden’s twenty-one line lyric “Look, stranger, at this island now” is a small miracle of blended echoes, turning borrowed words into new music. You can read the whole poem here:

https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.215337/page/n231/mode/2up

Written in lines of varying length, full of alliteration and assonance, and with a loose stanzaic rhyme scheme (abcdcbd), the poem imitates what it describes: “the swaying sound of the sea”. Nicholas Jenkins, in a superb close reading from his new critical biography, The Island: W.H. Auden and the Last of Englishness (Faber), admires its “rich verbal density” of “ceaseless inner joining”, a patterning he hears completed in the way the alliterating “s” words of the last line echo the “stranger” twenty lines above:

And all the summer through the water saunter.

That first line — “Look, stranger, at this island now” — also sets off an important external echo. The poem is often taken by critics to be “about” England, even though “this island” is not named. But that small word “this” tunnels back to Shakespeare, and John of Gaunt in Act II.i of Richard II, lamenting an idealised nation:

This royal throne of kings, this sceptred isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for her self

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in a silver sea

Which serves it in the office of a wall

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England

Gaunt’s anaphora (“This… this… this…”) suddenly runs out of things to call England — so he has to call it “this England”, which is only one step short of saying “this this”, the unnameable, essential thing. It’s a potent dramatic touch — eloquence meeting inarticulacy — and it has broken off into the language as a chip of national sentiment. There is a cosily reactionary magazine, for example, called This England which, as Wikipedia notes, “has a large readership among expatriates”.

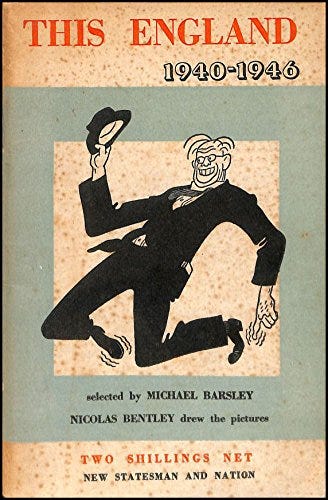

And there is also a long-running column of light-hearted British news stories called “This England” which the New Statesman magazine started in 1934 — one year before Auden (who was a New Statesman contributor) wrote the poem.

So to use the words “this island” in a poem is to echo the first and last syllable of a phrase filled with condensed patriotic feeling. Yet at the same time, by not saying “this England”, Auden also registers a difference. One way to read the title poem of Auden’s collection Look, Stranger! (1936) is as a meditation on the idea of “England” in the age of refugees from mainland Europe. On 15th June 1935, Auden — who was gay — had married Erika Mann, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann, so that she could gain British citizenship and escape Nazi Germany.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.