The Polish'd Pewter

The unique poetry of an eighteenth-century servant

‘Tis true our Parlour has an earthen Floor,

The Sides of Plaster and of Elm the Door:

Yet the rub’d Chest and Table sweetly shines,

And the spread Mint along the Window climbs

Mary Leapor, “The Month of August”

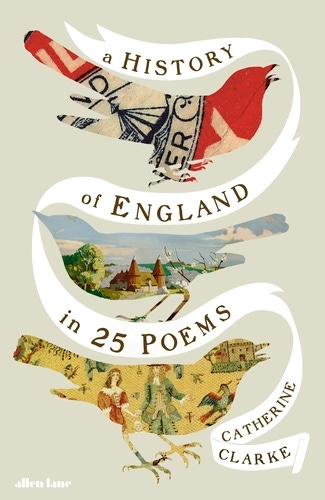

In this month’s Prospect magazine, I reviewed Catherine Clarke’s A History of England in 25 Poems (2025). If you create a free account, you can read the piece here:

I thought the book was a mixed success in treating poetry as history (publishing really needs to give up the neat structuring number!) But I was grateful for the discoveries to which it led. These included a poet who will now be a permanent part of my imaginative response to the words “eighteenth-century England”. Here is what I said:

The best chapters of this book are those where a lesser-known but skilful poem is recovered from neglect: there is pleasure to be had in the verse, and pleasure in the way it illuminates an era. It’s good, for example, to encounter John Dryden’s superb Annus Mirabilis (1667), with its documentary quatrains of the Great Fire of London (water to extinguish fires was traditionally kept in churches, hence the line “Some run for buckets to the hallowed choir”). And it’s even better, after this, to meet “Crumble-Hall” (circa 1745), a long poem by a domestic servant, Mary Leapor, who used the pungent mock-heroic couplet of Pope and Swift to describe someone doing the washing-up:

The greasy Apron round her Hips she ties,

And to each Plate the scalding Clout applies:

The purging Bath each glowing Dish refines,

And once again the polish’d Pewter shines.Virginia Woolf, who famously imagined the failed literary career of “Shakespeare’s sister”, would have loved Mary Leapor. Sadly, like Judith Shakespeare, Leapor also died young—and here Clarke’s historical close-reading hits a bullseye that resonates around the 18th-century world. Explaining why burial in a woollen shroud legally signified her relative poverty, Clarke contrasts the dead poet with her employer, Richard Chauncy, a textile merchant with the East India Company, who imported the luxurious fabrics that only the rich could afford to take to the grave.