Not all the poems we love are “great poems”. One of the more endearing moments in Ezra Pound’s critical prose is the essay “A Retrospect” (1918), which looks back on his early rules for Imagist poetry e.g. “to use absolutely no word that does not contribute to the presentation”. Such severe standards, Pound once believed, “would throw out nine-tenths of all the bad poetry now accepted as standard and classic”. But the end of “A Retrospect” admits there is a subjective element to taste. Naming “the few beautiful poems that still ring in my head” from the Imagist period, Pound comments:

These things have worn smooth in my head and I am not through with them, nor with Aldington’s “In Via Sestina” nor his other poems in “Des Imagistes,” though people have told me their flaws.

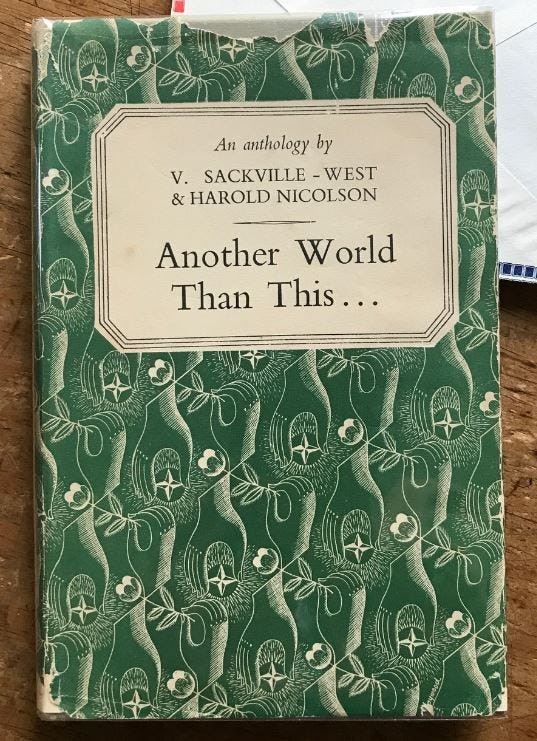

We can know a poem’s flaws and be a fan of it regardless. I feel similarly about the imperfections of a poem by an almost-forgotten seventeenth-century poet. I first read it in one of the small paperback anthologies published in the Penguin Popular Poetry series in the mid-Nineties. At the time, I was impressed that the editor had dug up such a rough diamond to include alongside Milton, Marvell and Donne. Subsequently, I discovered that the poem already had a long life as an anthology piece, going back at least as far as the 1930s, and coming to a wider readership through Harold Nicholson and Vita Sackville-West’s popular commonplace book, Another World Than This (1945), which — the editors said — was compiled from “underlinings” on their bookshelves. The manuscript which contains the poem, however, wasn’t printed until the 1950s. So to feature in a pre-war anthology, it must have been copied out by someone sitting in the British Museum who felt it was worth sharing. To quote the end of the original Dictionary of National Biography entry for its author, Ralph Knevet (1600—1671): “Some of the poems are worth printing.”

All of which confirms my feeling that there is something about this particular poem which warrants it a place alongside more skilful pieces of verse, both in anthologies and in my head. Knevet, said the historian Christopher Hill, was “a very minor poet”:

At his best, in his imitations of Herbert, he can produce an agreeable simple stanza […] At his worst, he perpetrates cacophony.

Hill is referring here to Knevet’s final work, A Gallery to the Temple, Lyrical Poems upon Sacred Occasions, which is self-consciously presented as a tribute to George Herbert, whose English poems appeared posthumously as The Temple in 1633. The poem I have in mind appears in A Gallery to the Temple. But it stands out in that sequence because it is not obviously an imitation of Herbert at all, or even a poem with a “sacred occasion”, beyond the coming of peace. And this subject matter reflects the fact that Knevet lived through something Herbert didn’t: the English Civil Wars (1642—1651). It is called, simply, “The Vote”, although there is no vote mentioned in it:

There are many things that a Pound-like editor might take a “pruning knife” to here. The first couplet, for example, falls into a pair of regular iambic pentameters (“The helmet now an hive for bees becomes”). But the snappy shorter couplet about turning pikes into rakes is less regular, and the following line veers even further from iambics as it tries to squeeze eleven syllables into ten: “And the keen blade, th’ arch enemy of life”. Then there is the aurally congested feeling of the rhyme sounds in the opening lines: “blade / degrade-” in lines 5-6 is a nice internal rhyme, but it is repeated immediately as “spade / made”, then followed by “retake / forsake”, a recycling from the “make / rake” couplet. It’s altogether too many long “a” rhymes at once.

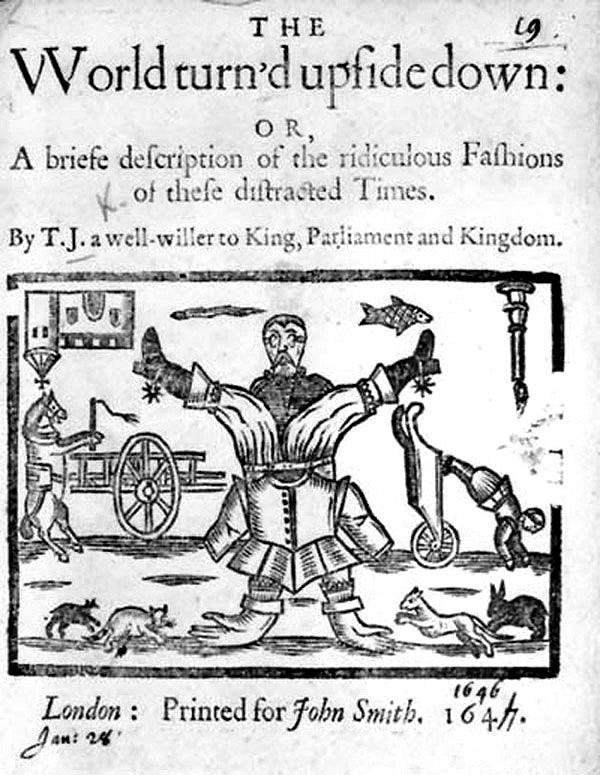

But in this rough texture I hear a kind of historical atmosphere: the poem’s jumbling-up of small animals and objects in these doggerel-like rhythms and tangled rhymes suggests the chaos of a world “turned upside down” by war. It’s a woodcut poem.

Another reasonable editorial objection to “The Vote” might be that it is repetitive. The critics who have commented on it note that Knevet elaborates the proverbial image from Isaiah 2:4 (“they shall beat their swords into ploughshares”) as well as similar images in Virgil’s Georgics (trans. Robert Fitzgerald):

Let me speak then, too, of the farmer’s weapons:

The heavy oaken plow and the plowshare[…]

A farmer with his plow will turn the ground,

And find the javelins eaten thin with rust,

Or knock the empty helmets with his mattock

The first sixteen lines of “The Vote” play a lot of variations on this theme. But they get away with it because they do so with a sense of on-the-spot improvisation. Knevet — who lived all his life in rural Norfolk, as a tutor to an aristocratic family and later a priest — sounds like a poet who has actually held a rake and a pruning knife, and seen swords and helmets lying around. As Alastair Fowler puts it in an insightful comment:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.