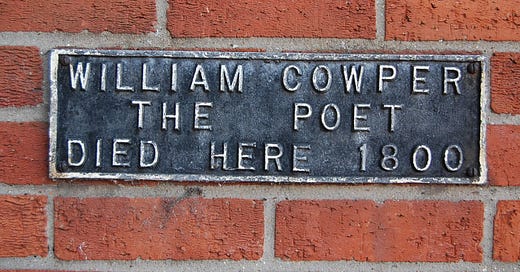

Living away from home at university in the Nineties, I was darkly amused to discover that the only famous poem ever written in the small town I had left behind is possibly also the most despairing in all of English literature. The poem was “The Castaway” (1799) by William Cowper (1731—1800) and the town was East Dereham in Norfolk.

Af…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Some Flowers Soon to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.