A prize instance of comma-spraying indulged in without rhyme or reason

G.V. Carey, Mind the Stop: A Brief Guide to Punctuation (1946)

If my criticism has had any influence at all, it’s on how the Poet Laureate uses commas. When Simon Armitage appeared on BBC Radio’s Desert Island Discs in May 2020, I was listening, in Covid lockdown, doing the washing up. I almost dropped my sponge when I heard presenter Lauren Laverne ask: “How do you handle reviews?”

Simon Armitage: I can think of a couple of occasions where people have said something and I’ve thought: “They’re absolutely right, I need to stop doing that.”

Lauren Laverne: What kind of thing?

Simon Armitage: Somebody once pointed out that — [laughs] it’s going to sound so trivial — that I often used a comma in the middle of the last line of my poems, and…

[both laugh]

Lauren Laverne: … they’re really splitting hairs if they’re getting down to that one.

Simon Armitage: Yeah, but I looked back through a lot of my poems and I thought, “That’s a good point”.

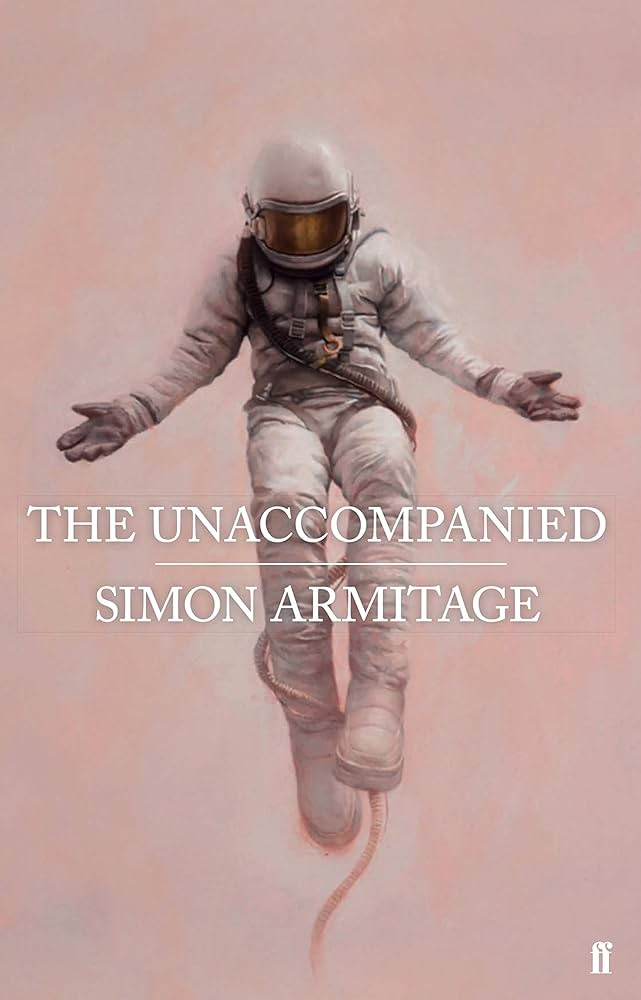

From my review of Armitage’s The Unaccompanied (2017):

The bulking-up of significance can lead to unsubtle underlining. “Prometheus”, for example, concludes with Armitage’s patented sign-off of two phrases spliced by a comma (“the glint in his eye, the makings of fire”), signalling the end of its riffing on the myth like a rock guitarist nodding to the band.

[Shortly after this review was published, I heard Armitage give a reading from some new work that I liked. I told him so afterwards, and he replied, drily: “No guitar solos.”]

Before I get too proud of this hair-splitting claim to fame, though, I also have to remember that I was once very wrong about a comma. One of the earliest reviews I wrote was of R.F. Langley’s Collected Poems (2000). I loved it, and would go on to edit Langley’s posthumous Complete Poems (2015). But as a finicky young critic, I also entered my caveats, querying the author’s “occasional weakness” for “private surrealism”, and citing the lines “Is it a comma’s wings / make such silky noise?” as “less convincing”. In a friendly letter Langley sent after the piece appeared, he kindly waited a page to correct me. The comma — as I did not know — is a butterfly. So, too, is the tortoiseshell, which whispers its wings when it hibernates. The question was not surrealism, but a speculation in natural history. I read up on butterflies, and whenever I’ve spotted the scalloped orange flutter of a comma since (its name comes from a white mark on the underside of its wings) I’ve remembered Roger Langley.

I began to think about commas this week after hearing the Dutch poet, Sasja Janssen, and her translator, Michele Hutchison, read from their new book, Virgula (Prototype), which was nominated for several prizes in Holland. Speaking afterwards, Janssen said that she began the sequence after reading this passage from Ben Lerner’s essay The Hatred of Poetry (2015) about the use of the “virgule” — or forward slash, or scratch comma, or solidus — to indicate line breaks in critical prose (e.g. “a red wheel / barrow”):

“Virgule”: from Latin virgula — a little rod, from virga : branch, rod. We hear in it the Virgula Divina — the divining rod that locates water or other precious substances underground, a rod that mediates or pretends to mediate between the terrestrial and the divine. We hear (although the etymology is disputed) the name of the ancient poet known to us as Virgil, Dante’s guide through hell. And we hear the meteorological phenomenon known as “virga,” my favourite kind of weather: streaks of water or ice particles trailing from a cloud that evaporate before they reach the ground. It’s a rainfall that never quite closes the gap between heaven and earth, between the dream and fire; it’s a mark for verse that is not yet, or no longer, or not merely actual.

In Janssen’s vividly inventive long poem, “virgula” — which also once meant the stem of a musical note — becomes both a muse to be invoked and the fleeting, breathing mark of the comma (French: virgule). In the penultimate poem she considers the poetic life of her “Virgulas”:

commas sway their way to a full stop, but mine never sway

to their end

they attack me from a line of sunlight between the curtains

jostling with amusement when they latch on

the shapes are already there, but you need to find the language

to capture them in,

I long for a full stop, but my Virgulas are wary

of employing them

As you can hear from this short extract — in which the commas might again be butterflies, at least in my mind’s eye — it’s an English translation with its own subtle energy and sound patterning. It’s great to see Prototype, an independent UK publisher, bringing genuinely contemporary European poetry to a wider readership.

Finally, to Lauren Laverne and all the haters: if you think I’m splitting hairs, I’m not alone. An illuminating new book on the writing process, Rosanna McGlone’s The Process of Poetry (Fly on the Wall Press), contains interviews with contemporary British poets about the drafting process of a single poem. Here are two quotations:

The commas in […] the tenth stanza took me some time to decide on. I wondered if a comma was required after “in the dark”, putting it in then cutting it again. Commas did feel necessary, however, after “at dawn” and “after sunlight”, for added gravitas. (Regi Claire)

I made one further change to the punctuation in the final line, introducing a comma between “multiply” and “strain”. I wanted to split the two words into two distinct actions. That way it would feel less glib. (George Szirtes)

On the other hand, I am also fond of Gertrude Stein’s rejection of the whole business model of Big Comma:

What does a comma do.

I have refused them so often and left the out so much and did without them so continually that I have come finally to be indifferent to them. I do not now care whether you put them in or not but for a long time I felt very definitely about them and would have nothing to do with them.

As I say commas are servile and they have no life of their own, and their use is not a use, it is a way of replacing one’s own interest and I do decidedly like to like my own interest my own interest in what I am doing.

NOTES

Virgula (Prototype): https://prototypepublishing.co.uk/product/virgula/

The Process of Poetry (Fly on the Wall Press): https://www.flyonthewallpress.co.uk/product-page/the-process-of-poetry-edited-by-rosanna-mcglone

Gertrude Stein on Punctuation: https://writing.upenn.edu/epc/authors/goldsmith/works/stein.pdf

This is lovely, and I enjoyed the definition of virgula as 'the divining rod that locates water or other precious substances underground, a rod that mediates or pretends to mediate between the terrestrial and the divine'. Hearing the word 'virgule' gave me a Proust-like flashback to French dictation classes at school, and the pleasure of turning that rather leaden word (as it seemed to me then) into a simple little flick on the page.

Or there’s Adorno’s essay on punctuation-marks in ‘Notes to Literature’.