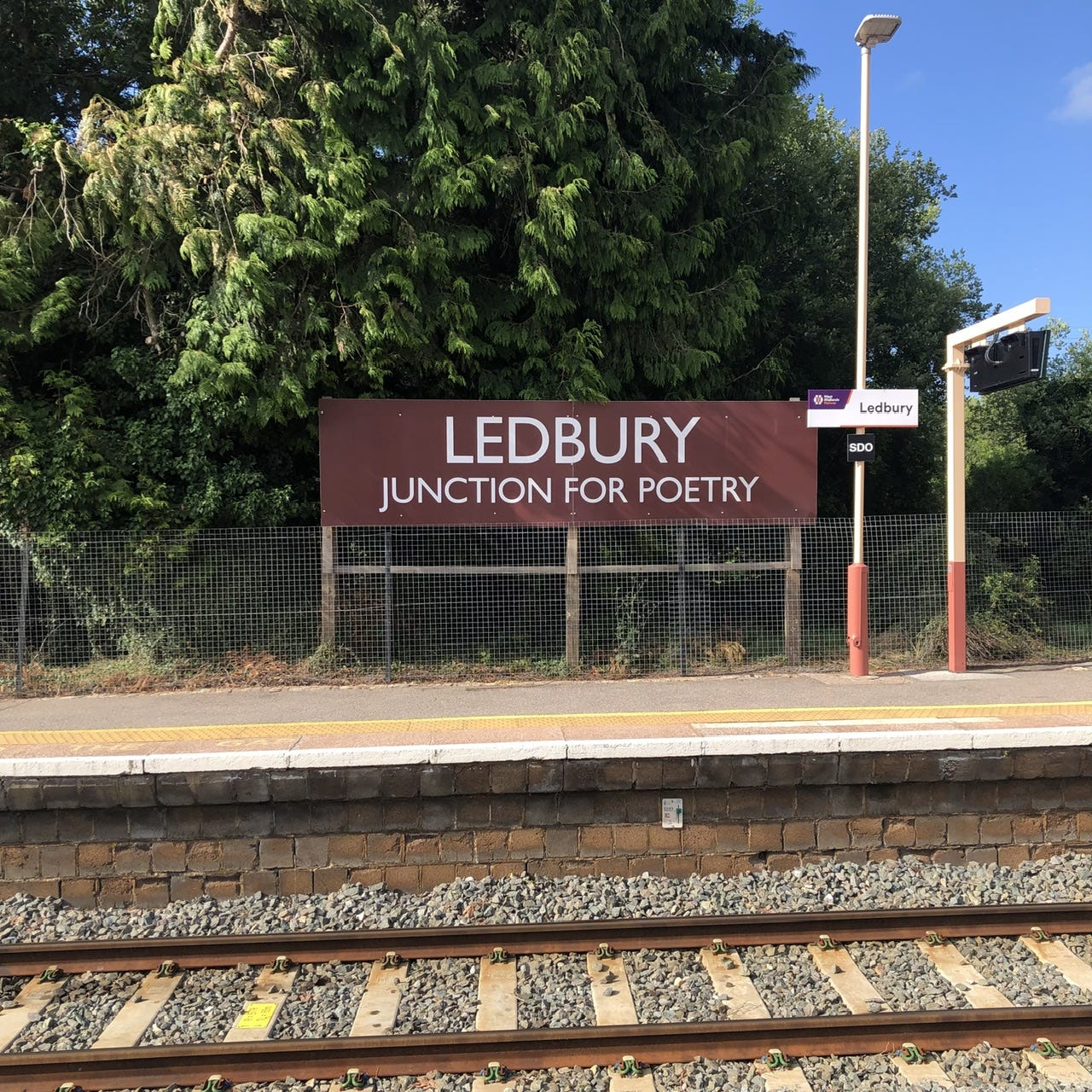

Last weekend, I went to Ledbury, Herefordshire for the annual poetry festival that’s been running there since the Nineties. It’s hard to think of an English town with more poets literally written into it. Not only do they have John Masefield High School, named after the long-running Poet Laureate (1930—1967) who was born in Ledbury in 1878; they also have the Barrett Browning Institute, built to honour the town’s most famous Victorian poet, and now known as The Poetry House; plus every other street name seems to commemorate a poet connected with the area, from The Langland (Piers Plowman begins in the nearby Malvern Hills) to Auden Crescent and Frost Close.

I did a double take, though, when I saw the Day Lewis Pharmacy, just down the road from the Poetry House — surely not the family business of Cecil Day-Lewis (1904—1972), who succeeded Masefield as Laureate? I began to feel as though I had slipped into the kind of dream I have after reading too many anthologies before bed. Google told me there was a connection, but not via Ledbury: the Day Lewis Group, one of the largest independent pharmacy chains in the UK, was founded in 1975 by Kirit Patel, who named his business after the late laureate. There are now over 250 branches across England — but almost none where I live in East Anglia, hence my double take.

From East Anglia to Herefordshire is a long journey, so this week’s post is a selection of poems from new books that I enjoyed reading on the train, plus one that I was reminded of by another landmark Ledbury building. I was at the festival to talk about the excellent Ledbury Poetry Critics programme, whose latest report on diversity in poetry reviewing is now available: https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/new-and-international-writing/emerging-critics/ledbury-poetry-critics-report-2025/. The next day, it was a nice surprise to learn that my anthology, The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, was also knocking around town in the form of a handout for a workshop by the poet Caleb Klaces. So, as a prelude to the prose poems below, here’s my introduction in a nutshell:

One souvenir I brought back from Ledbury was a little Versopolis pamphlet by the Cypriot poet Alexandros Chronides. It contained facing-page versions of the same poems in Greek and English, but with a twist: the poems were originally written in English (Chronides studied Philosophy and Economics at Edinburgh) and later translated by the poet into Greek. I like the snack-like nature of this short piece:

Also on the Ledbury Poetry Critics panel was Isabelle Baafi, who took part in the scheme, and has just published her first collection, Chaotic Good (Faber). This unrhymed sonnet packs a lot into its long lines, comedy and tragedy counterpointed in the “maelstrom” of its compelling but unpredictable sound patterning:

One Ledbury event I enjoyed being in the audience for was a discussion by Kimberley Campanello and Philip Terry of their in-progress experimental translations of Dante. Campanello explained how her Divine Comedy will change all proper names to pronouns, bringing out the lyric in the epic. The final prose poem from her new collection, An Interesting Detail (Bloomsbury), also touches movingly on this idea:

I’m a fan of everything Will Harris has written, in verse and prose. So as I caught the branch line from Birmingham to Ledbury, heading into what might be called Deep England, it was a pleasure to read and re-read Speakee Stonehenge (Blown Rose), a prose poem sequence which brilliantly gathers and scatters ideas of national identity into “many dispersed points speaking” across its ingeniously interwoven paragraphs:

A pocket-sized publication that provided the ideal alternative to scrolling on my phone as I waited on platforms was the first issue of

, a new print poetry magazine which is also on Substack. The reviews section is happily snappy and eclectic. Ira Lightman’s discussion, for example, of Lyn Hejinian’s uncollected poems — largely written before her great prose poem My Life (1980) — calls them “early bitty pieces” by “the widest eye of her generation”, but ends generously with a whole short poem “which may take some reader’s fancy”, as it did mine.Finally, a poem that I liked when I first read it in Hwaet! 20 Years of Ledbury Poetry Festival (Bloodaxe), by the American poet Kay Ryan, who wrote it on the spot and read it at the festival in 2012. It’s about the posts that support the raised seventeenth-century timber Market House. John Masefield recalled in a poem on his early life in Ledbury how “a market building stood / Propped upon quarres of of chestnut-wood”. But he was wrong about the tree: it was later found the posts were made of oak. His use of the archaic word “quarres” though (“the carcass of a hunted animal”) suggests a metaphorical affinity with Ryan’s riddling image of an elephant tamed by the unseen violence of tools to a “patient beast” on “anchor stone”. There is always more to a Kay Ryan poem than its short lines and zigzag rhymes at first imply, and here I think it is the history of British imperialism through which the Market House has “stood and stood” — as a place where you might buy the wares of Masefield’s famous “Cargoes”.

NOTES

I wrote about my own experience of growing up in a small town that commemorates a once-famous poet here:

The Winner of Sadness

Living away from home at university in the Nineties, I was darkly amused to discover that the only famous poem ever written in the small town I had left behind is possibly also the most despairing in all of English literature. The poem was “The Castaway” (1799) by William Cowper (1731—1800) and the town was East Dereham in Norfolk.

And I wrote more about Kay Ryan’s use of rhyme here:

![Six Tendencies of the Prose Poem (Adapted from the Introduction to The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, ed. Jeremy Noel-Tod) 1. Drawing on Other Forms Forms such as 'the anecdote, the aphorism, the sketch, the dialogue, the essay, the fairy tale, the fragment, the joke, the myth, or the short story (xxi).' 2. A Feeling of Expansiveness The 'distinctive feeling to which the prose poem gives form: expansiveness (xxix).' 3. A Moment of Metaphor That expansiveness is 'often created by a moment of metaphor giving it a sudden lift, like the flare of the burner in a hot-air balloon (xxxi).' 4. Dwelling on Image over Narrative 5. Returning to the Beginning The 'drawing of a verbal circle (xxviii).' 6. Jokes that Become Serious 'Prose poems [...] often feel like jokes that overshoot their punchlines into something more serious (xxv).' Six Tendencies of the Prose Poem (Adapted from the Introduction to The Penguin Book of the Prose Poem, ed. Jeremy Noel-Tod) 1. Drawing on Other Forms Forms such as 'the anecdote, the aphorism, the sketch, the dialogue, the essay, the fairy tale, the fragment, the joke, the myth, or the short story (xxi).' 2. A Feeling of Expansiveness The 'distinctive feeling to which the prose poem gives form: expansiveness (xxix).' 3. A Moment of Metaphor That expansiveness is 'often created by a moment of metaphor giving it a sudden lift, like the flare of the burner in a hot-air balloon (xxxi).' 4. Dwelling on Image over Narrative 5. Returning to the Beginning The 'drawing of a verbal circle (xxviii).' 6. Jokes that Become Serious 'Prose poems [...] often feel like jokes that overshoot their punchlines into something more serious (xxv).'](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!cJOa!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F0c7b72fd-097e-4582-adbb-f6a3a209abef_1280x1280.jpeg)